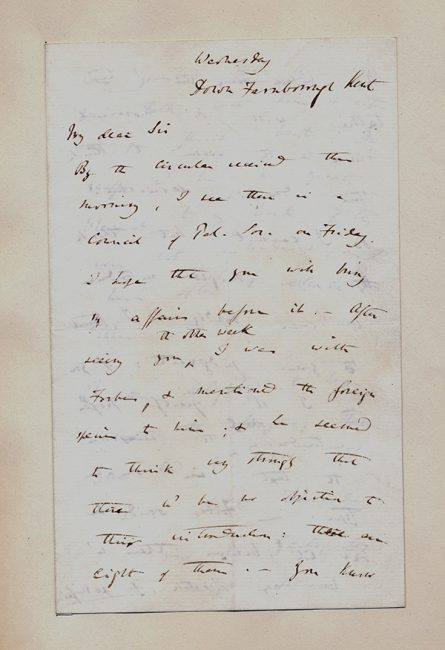

Charles Darwin’s passion for studying the geological record of fossils and theorizing about the origin of species—including the evolution of the human species—as resulting from descent from common ancestors by means of natural selection shook the foundations of the mid-Victorian world and set the future course of science. Everyone knows that story. Less well known is Darwin’s passion, especially in the late 1840s, for classifying invertebrates. In 1851, he published Fossil Cirripedes, a work dedicated to anatomizing and reclassifying barnacles. To offset the extra costs of the illustrated plates, he applied in the year before to the Palaeontographical Society, which was founded in 1847 by J. S. Bowerbank, an amateur geologist, to encourage the publication of illustrations of British fossils. In this letter, Darwin asks Bowerbank to make the case before the Society for supporting the illustrations of foreign species, too, in his monograph. Mark Samuels Lasner acquired this letter unexpectedly, when it turned up unannounced in a volume of manuscript testimonials to the Zaehnsdorf firm of bookbinders, sold to him by Oak Knoll Books.

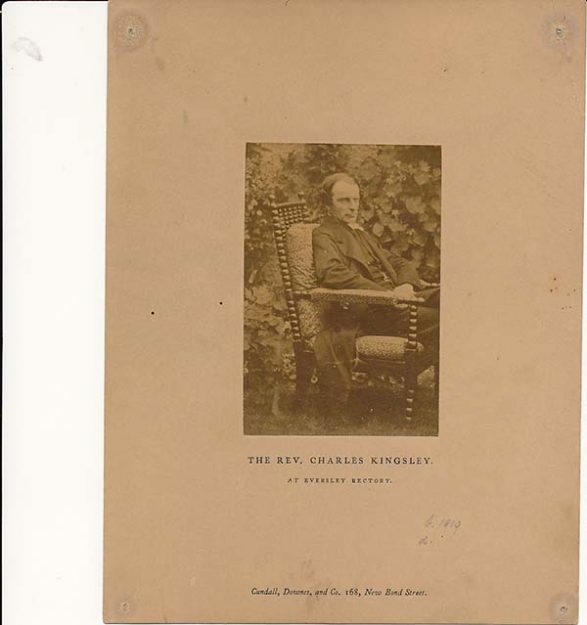

Charles Kingsley (1819–1875) was a man of multiple and seemingly antithetical passions. His contemporary, Philip Gosse (1810–1888), was tormented by his inability to reconcile religion and evolutionary theory (as recorded in Edmund Gosse’s 1907 tragi-comic memoir, Father and Son). Kingsley, on the contrary, managed to lead a successful life as an Anglican priest while advocating for controversial scientific ideas. He joined both the Geological and the Linnaen Societies; he corresponded with Charles Darwin; he became close to Darwin’s disciple, the biologist Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895); he invoked evolutionary principles in his popular work of fantasy fiction, The Water Babies (1863), which also expressed his passion for social reform. His abiding private obsessions, however, were publicly unspeakable erotic ones that focused mainly, though not exclusively, on the body of his wife, Frances (“Fanny”) Grenfell.

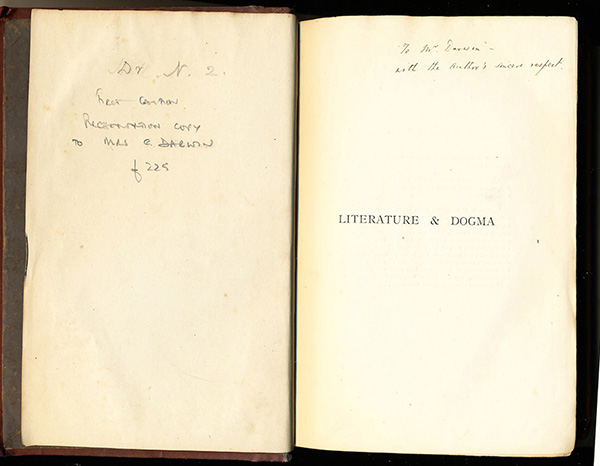

Precisely why Matthew Arnold chose to present Charles Darwin with a copy of his Literature and Dogma remains unknown. They were not friends; indeed, they barely knew one another, and Arnold had to use as go-between Darwin’s disciple, Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895), to convey this inscribed copy to him. Why Arnold thought that Darwin would wish to read his treatise on how new, more poetic approaches to the Bible could benefit modern Christianity is equally unclear. Literature was Arnold’s deepest passion, but he certainly did not believe that it was Darwin’s. In a December 1875 letter to his youngest sister, Frances (1833–1923), Arnold would later write, “Old Darwin . . . though actively fierce against nothing, says that he cannot conceive what need men have either of religion or of poetry; his own nature, he says, is amply satisfied by the domestic affections and by the natural sciences.” Darwin’s response to the gift was an effusive thank-you note. The notes written in this copy, however, are in the hand of Darwin’s daughter, Henrietta Darwin Litchfield (1843–1929), suggesting that it was probably she, and not the intended recipient, who actually read it.

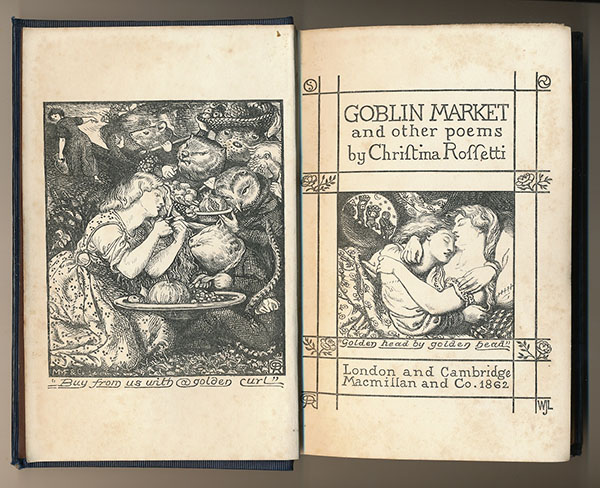

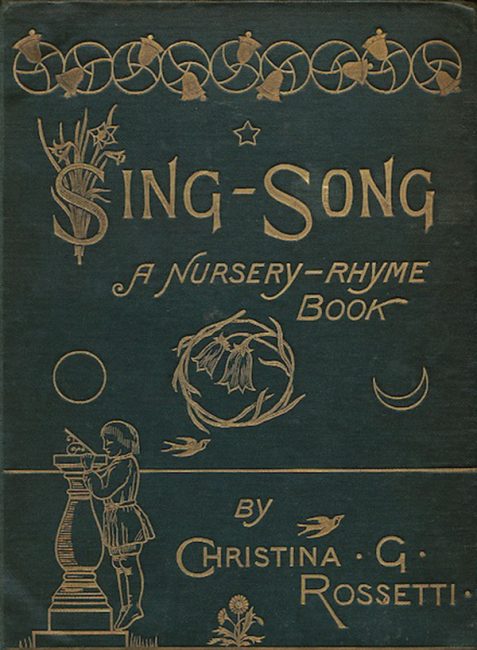

The major passion of the poet Christina Rossetti’s life was her religion—specifically, her Anglo-Catholicism. She wrote, nonetheless, one of the most sexually charged works by any Victorian woman. “Goblin Market” is an unforgettable fantasy about two sisters. One nearly dies, after giving in to her desire for the addictive wares of magical fruit-sellers; the other saves her through self-sacrifice, allowing the goblins to pelt her with fruit and then letting her sister suck the juices from her skin. Rossetti’s brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, produced the frontispiece image for the volume in which this poem appeared, including among the creatures in the marketplace a version of his favorite animal, the wombat. Christina Rossetti inscribed this copy to Mrs. Amelia Barnard Heimann. In the letter shown here, she spoke of her anxiety in presenting it, for she feared that her dear friend, who was Jewish, would be offended by another poem in the same collection, “Christian and Jew: A Dialogue.” That there were other sides to Rossetti’s talent, beyond the erotic and the pious, is confirmed by the second volume on display: Sing-Song, a work for children, with charming illustrations and a cover design by the Pre-Raphaelite artist, Arthur Hughes (1832–1925). This copy is inscribed to her brother, the writer and editor William Michael Rossetti, who shared none of her religious fervor, yet to whom she was very close.

Israel Zangwill, 1864–1926. Children of the Ghetto. London: William Heinemann, 1892. Inscribed by the author in each volume, v. 1 “‘My first-born 'Children’—Triplets I Zangwill”; v. 2 “The second child IZ”; v. 3 “The third of the brood IZ.”

Among the saddest works of Victorian fiction was “Transitional” from Israel Zangwill’s Ghetto Tragedies (1899), about an observant immigrant Jew who gallantly tries, but fails, to accept his daughter’s passion for a Christian Englishman. Ghetto Tragedies was one of several collections of short stories focused on British Jews caught between the preservation of religious traditions and assimilation, in which Zangwill capitalized on the unexpected popular success of Children of the Ghetto. A triple-decker issued when that Victorian publication format was falling out of fashion, Zangwill’s 1892 novel explored the plight of a young Jewish woman from “a dull, squalid, narrow thoroughfare in the East End of London,” who becomes an intellectual, but grows up with no sense of where she belongs in life. In this copy, Zangwill has laughingly described each of the three volumes in familial terms. At the time, they were his only “Children.” Not until 1903 did he marry the writer Edith Ayrton (1879–1945), with whom he shared a passion for the women’s suffrage movement, and produce a “brood” made of flesh, rather than paper.

Alice Meynell, 1847–1922. Collected Poems of Alice Meynell. London: Burns & Oates Ltd., 1913. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed “To John S. Sargent with all kind remembrances from the writer May 1913”; with autograph letter to Sargent, 22 May 1913.

Despite being married, Alice Thompson Meynell was an object of worshipful passion for several Victorian authors of different generations, including Coventry Patmore (1823–1896), George Meredith (1828–1909) and Francis Thompson (1859–1907). Her own chief passions were Roman Catholicism, to which she had converted, and poetry. She never stopped writing, even while raising eight children with her husband, the journalist and publisher, Wilfrid Meynell (1852–1948). Among her strictly platonic admirers was the artist John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), whose interests were more homoerotic. Ten years before the publication of her Collected Poems, Sargent had, at the behest of Patmore, drawn the soulful portrait of Meynell that was reproduced as the volume’s frontispiece.

Michael Field [Katharine Harris Bradley, 1846–1914, and Edith Emma Cooper, 1862–1913]. Whym Chow: Flame of Love. London: Eragny Press, 1914. Author’s presentation copy, inscribed by Katharine Bradley to Louisa Ellis “Louie Ellis from Michael Field Spring 1914.”

When it came to forbidden passions, hardly anyone in late-Victorian Britain could match the aunt-and-niece pair, Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, for sheer numbers of them. Not only were they both women who loved women, but they were enamored of one another, despite their close familial ties, and considered themselves a married couple. Writing together as “Michael Field” (one of several pen names), they began by producing verse plays and volumes of poetry inspired by Sappho and Renaissance art; later, however, they celebrated their conversion to Roman Catholicism, further separating them from the Protestant social circles of their birth. Yet their most surprising affair of the heart was with their dog. After he died in 1907, they credited Whym Chow’s spirit with drawing them irresistibly to Christ and to Catholic theology. “Michael Field” extolled this miraculous event in Whym Chow, Flame of Love, the last and rarest work of the Eragny Press, only twenty-seven copies of which were printed by Esther Pissarro (1870–1951), wife of Lucien Pissarro. The copy on display is inscribed to Louisa Ellis (known as familiarly as “Louie”)—sister of their friend, the critic and sexologist Havelock Ellis (1859–1939)—who collaborated with Bradley and Cooper in making a number of the aesthetic dresses that they wore.