Henry Howard, 1843–1934

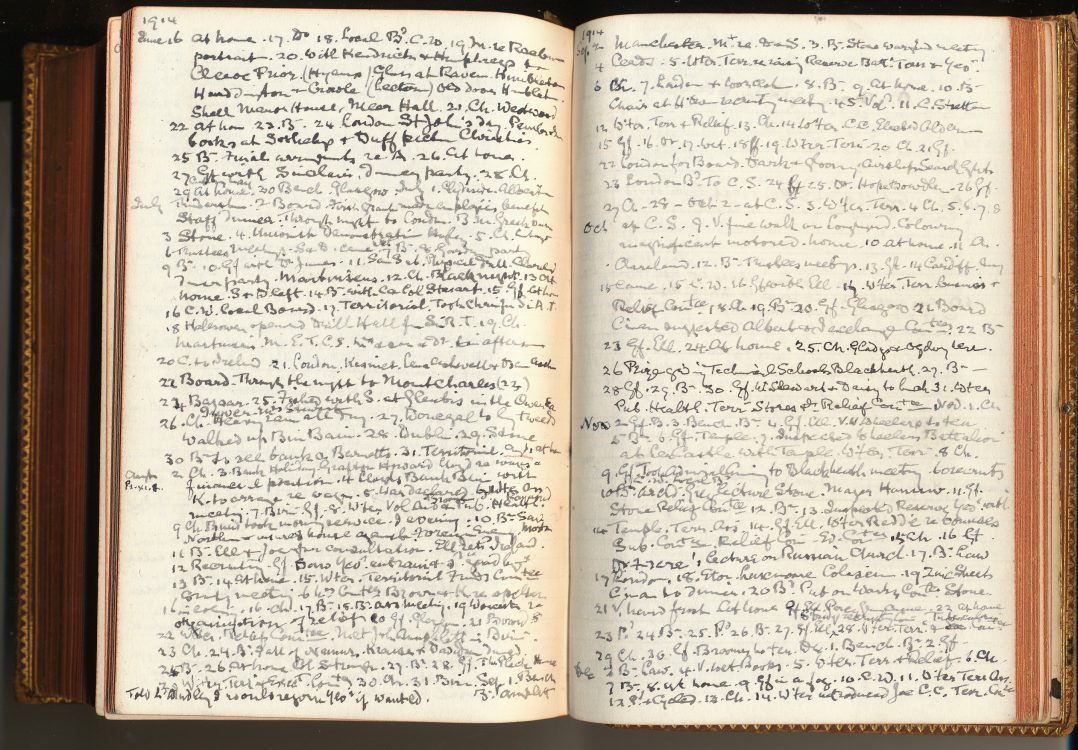

The diary of Henry Howard of Stone House – Kidderminster autograph manuscript signed, 1883-1926

Would anyone today know the name of Samuel Pepys, if it weren’t for the diary he left behind? Henry Howard—a late-Victorian industrialist, inventor, sportsman, and an amateur musician and artist—has attained no equivalent fame, but he did keep a diary for much of his adult life and dutifully recorded each day’s public and private events, as they affected him. His wartime entries are brief, but telling, as he reports on the declaration of war on 5 August 1914; his involvement with the “Territorials” and the “yeomanry” (elements of the volunteer army reserve organized by county and region); the progress of various battles; the challenges of rationing; and the military career of his eldest son, Geoffrey—who, after his war service in France and Italy, was promoted to lieutenant general and knighted. Howard himself oversaw war production at Stewart and Lloyd’s, the British steelworks firm, while holding the rank of colonel in the local yeomanry.

Adrian Stokes, 1854–1935

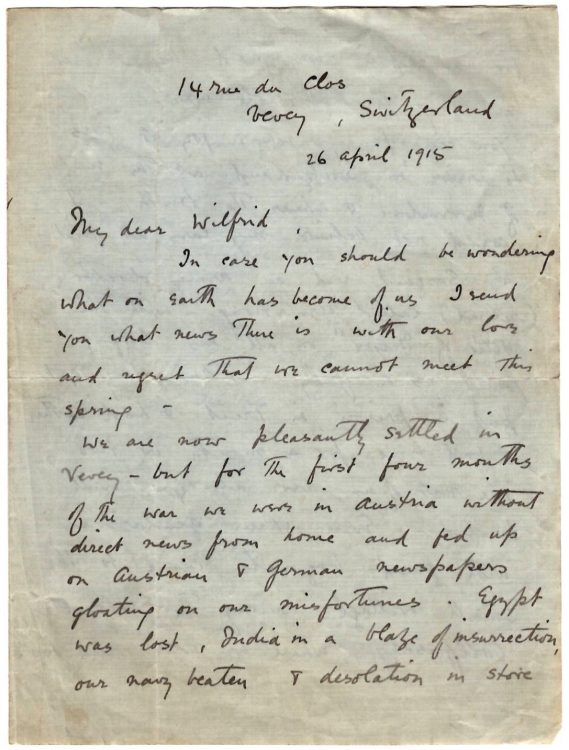

Autograph letter signed to Wilfrid Meynell, 26 April 1915

For artists who were accustomed to leading cosmopolitan, peripatetic lives and traveling across Europe unimpeded, the outbreak of war presented unexpected hazards. Both the English-born Adrian Stokes and his wife, the even better known “Newlyn School” painter Marianne Stokes, who was Austrian by birth, found themselves trapped in Munich as the conflict began and had to flee by way of Switzerland. This letter to Wilfrid Meynell, the critic and poet, gives an account of their travels (and travails), while also mentioning that their friend, the American painter John Singer Sargent, had successfully made his way back to England.

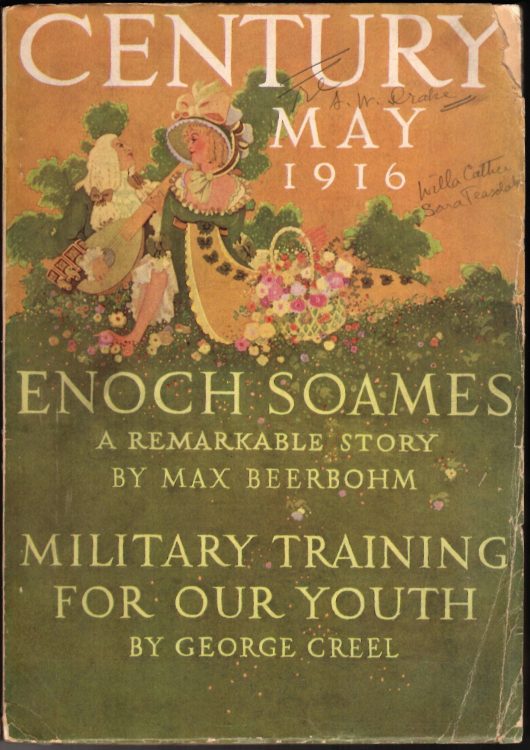

The Century, May 1916

New York: The Century company, 1916

When Arnold Bennett asked him in 1914 to do official work for the national effort, Max Beerbohm—who was well known as a late-Victorian caricaturist, wit, and dandy—refused. His talents, he said, were unsuited to propaganda. “The war,” he told Edith Wharton, “is not a subject for comedy.” (Beerbohm did draw a few cartoons of topical subjects, notably for Edith Wharton’s The Book of the Homeless and for John Galsworthy’s magazine, Reveille.) Exiled from Italy, where they had been living since 1910, Beerbohm and his wife Florence, an American actress, spent the war years at Far Oakridge, the Cotswolds home of his dear friend, the painter William Rothenstein. While there, Beerbohm escaped into the past, focusing on the fin de siècle and on the Pre-Raphaelite painters and poets of an earlier generation. One result was the series of watercolors later exhibited and published as Rossetti and his Circle. Another was his most famous story, “Enoch Soames”—about an imaginary, time-traveling Decadent of the 1890s—which first appeared in the Century magazine, placed somewhat incongruously next to an article on army training.

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956

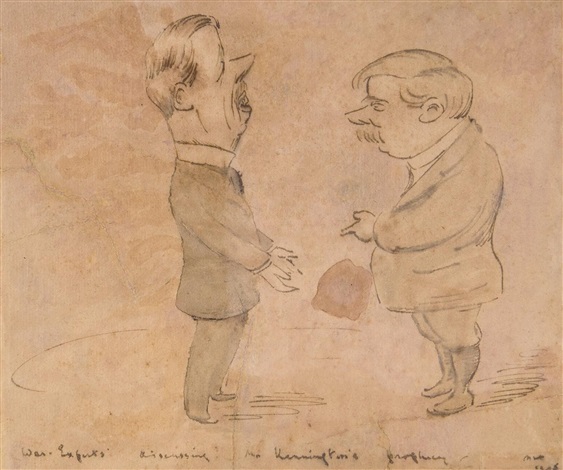

War-experts Discussing Mr. Kennington's Prophecy

ink and watercolor on paper, 1916

The figures depicted here are in fact the writers H. G. Wells and Arnold Bennett, and Beerbohm’s reference to them as “war experts” is meant ironically, though both authors weighed in often with their opinions about the conflict. The title of Wells’s 1914 polemic, The War That Will End War, likely gave rise to the First World War being known as “the war to end all wars,” while his novel, Mr. Britling Sees It Through (1916), explored the challenges of dealing with life on the home front and with the deaths of loved ones in battle. Bennett, who had been living in France for ten years before the war began, joined the Ministry of Information, in charge of propaganda for France. Beerbohm knew both Wells and Bennett—he had done earlier caricatures of them and parodied their writing styles in A Christmas Garland (1912)—but the joke about “Mr. Kennington” remains obscure. The reference is probably to the painter and sculptor Eric Kennington (1888–1960), best known today for his illustrations to T. E. Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Kennington fought on the Western Front and painted the men of his own unit in a work on glass titled The Kensingtons at Laventie, Winter 1914, which became one of the best-known images of the war. He was later appointed an official war artist.

Wilfrid Meynell, 1852–1948

Aunt Sarah & the War: A Tale of Transformations

London: Burns & Oates ltd., [1914?]

Although primarily a journalist and critic, Meynell wrote occasional verse and fiction. With his wife, the far-better-known poet Alice Meynell, he was also the center of a circle of English Catholic writers. This volume of imaginary letters exchanged among a group of fictional characters—Captain Owen Tudor (who is fighting in France), his aunt, and a female cousin—ends with the heroic death of the Captain at Ypres. Both this book, which was a surprise bestseller, and its sequel, Halt! Who Goes There? (1916), were issued by Burns and Oates, the Roman Catholic-focused publishing firm owned by Meynell—hence the anonymous publication. This copy is inscribed “With the affection of the Author, and all good wishes to R. & M. Z. for the year of fate 1914.” The recipients were Rufus Ferdinand Zogbaum, Jr., an admiral in the U.S. Navy, and Margaret Montgomery Zogbaum, American friends of the Meynells. Their eldest son, Wilfrid Meynell Zogbaum (1915–1965) was a painter and sculptor. In the accompanying letter from Buckingham Palace, the King’s private secretary, Lord Stamfordham, acknowledged the gift of Aunt Sarah & the War to George V.

Alice Meynell, 1847–1922

The Last Poems of Alice Meynell

London : Burns, Oates and Washbourne Ltd., 1923

Alice Meynell, who was one of the most important late-Victorian women poets, produced her own lyrical meditations on the war in the volume Poems on the War in 1916. Throughout the war, she endured air raids and German bombing, but also conflict within her family, when her son Francis declared himself a conscientious objector and refused to fight. After her death, her husband inscribed this presentation copy: "To her dear John Drinkwater From Wilfrid Meynell 1923.” Drinkwater was part of the circle known as the “Dymock Poets” and was a close friend of the famous soldier-poet, Rupert Brooke.

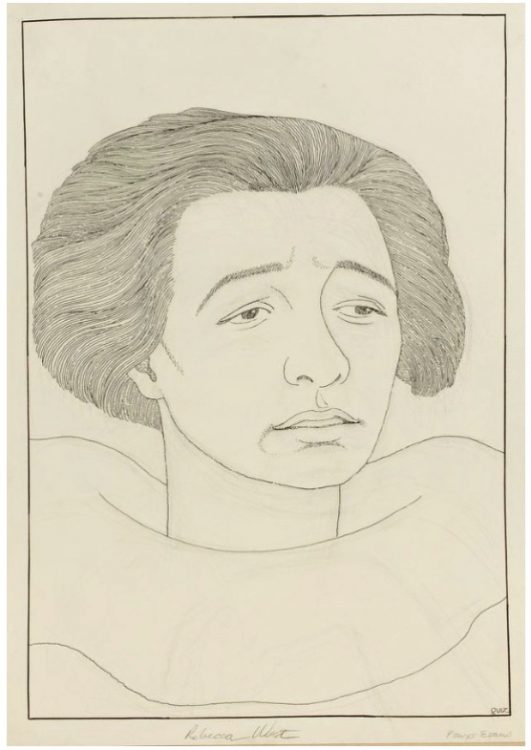

“Quiz” [Powys Evans] 1899–1982

Rebecca West

Pencil on paper, [ca. 1925]

Margaret D. Stetz Collection, on loan to the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The writer born with the name Cicely Fairfield—who called herself “Rebecca West,” after a character in Ibsen’s play Rosmersholm—made her reputation at a young age through her outspokenness. In leftist periodicals before the war, she wrote forthrightly about social injustice and British politics from a pro-suffrage, feminist perspective. She also took on the literary establishment in a series of book reviews, including one that brought her to the attention of H. G. Wells. Though he was much older and married, they embarked on a ten-year-long relationship that produced a son, Anthony West, who was born just as the war began. Forced to keep a low profile during the war, while hiding the existence of her child, she wrote admiringly of women who were active in doing war work, such as those who risked their lives in factories that made cordite (a highly incendiary component of explosives). Meanwhile, she produced a minor explosion of her own with a short and irreverent study of Henry James, published in 1916.

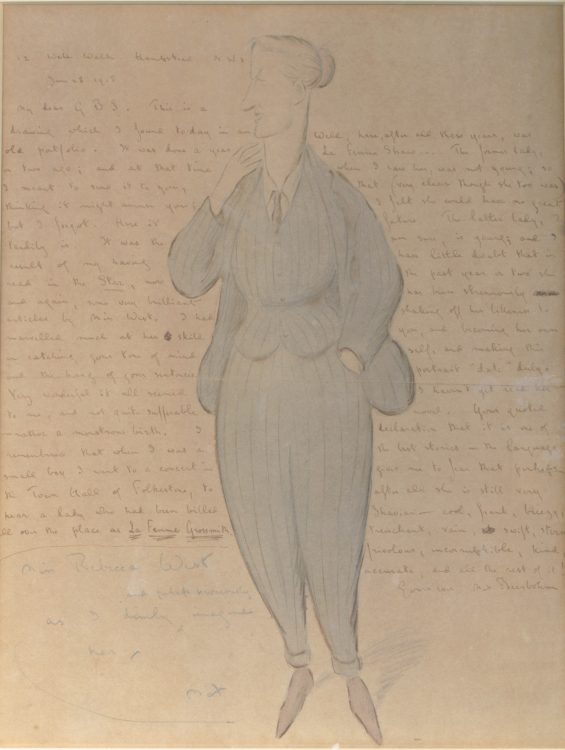

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956

Miss Rebecca West as I Dimly and Perhaps Erroneously Imagine Her

Pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, [ca. 1917]

In the accompanying letter addressed to George Bernard Shaw, Max Beerbohm explained that he had “done this drawing a year or two ago . . . the result of having read in the Star, now and again, some very brilliant articles by Miss West,” whom he had never met. The depiction shows Rebecca West—the feminist and suffragette, who in fact wore extremely feminine, glamorous clothes—as a clone of Shaw, dressed in one of his characteristic Jaeger suits, merely because she, too, was a socialist.

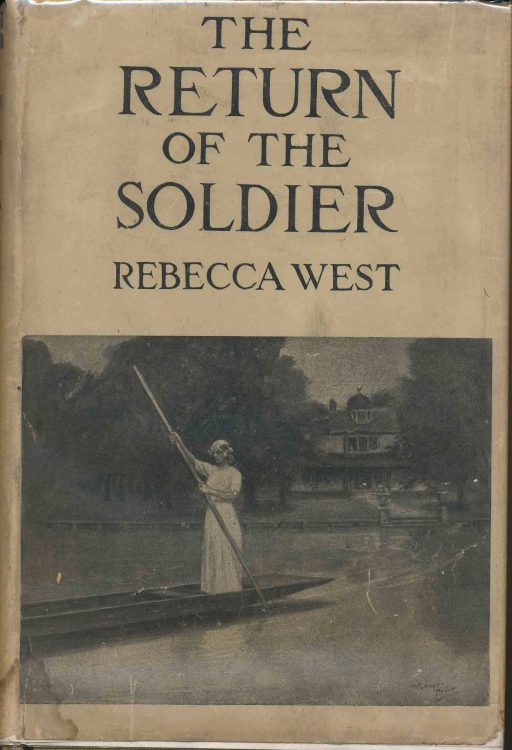

Rebecca West, 1892–1983

The Return of the Soldier: With Illustrations by William Price

New York: The Century company, 1918

West’s novel was one of the first to discuss the newly diagnosed condition of shell shock and to represent the devastating consequences for themselves and others, when soldiers came back from the battlefield with what we now call post-traumatic stress disorder. Her narrative was set during the war in an English country house occupied by women—the soldier’s wife and cousin—who must confront the fact that everything from the past fifteen years has been erased from his memory, and that he remembers only his former attachment to a woman of a lower social class. In the crisis that ensues, it is up to the three women who love the soldier to decide how and whether to make him “well” again, knowing that to do so will mean sending him back to the Front, where he is likely to die. West portrayed war not as a glorious enterprise for men, but as the source of profound moral dilemmas for women, which also shattered or solidified their bonds with one another. For its publication in the United States, however, this deeply philosophical meditation was given an inappropriately conventional set of illustrations, making it look like light romantic fiction.

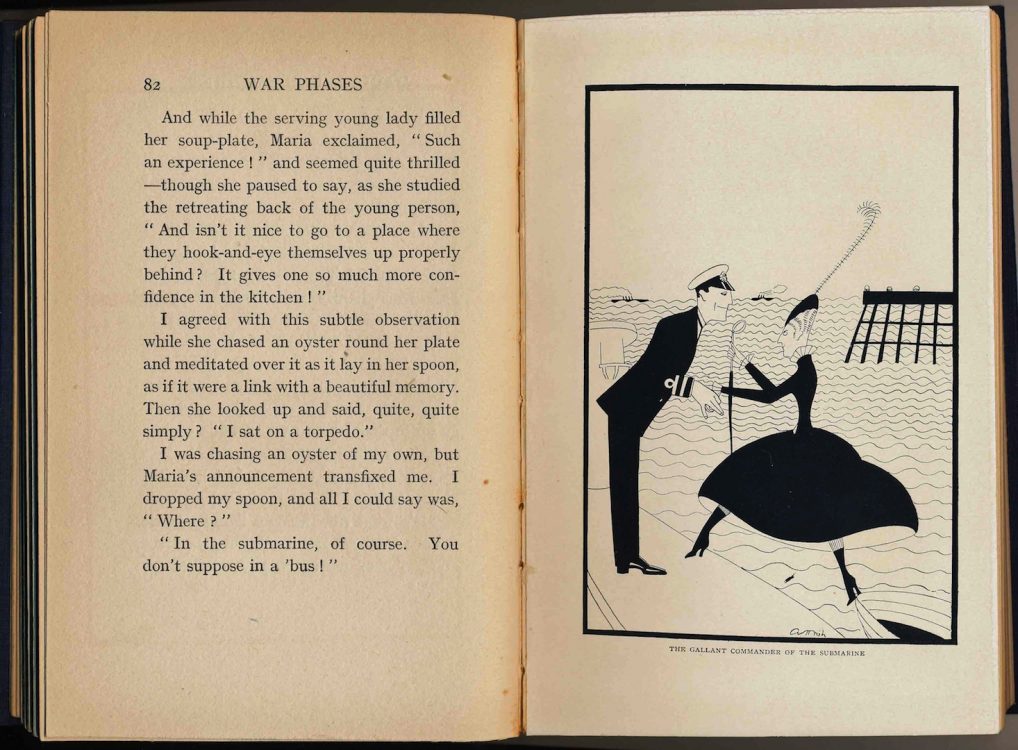

Mrs. John Lane, 1856–1927

War Phases According to Maria: Illustrated by A. H. Fish

London: John Lane, 1917

In 1898, the American author Annie Eichberg King married the London publisher John Lane (co-founder, with Elkin Mathews, of the Bodley Head firm). Continuing a transatlantic existence and publishing under the name “Mrs. John Lane,” King enjoyed considerable popularity with her series of comic sketches about the upper-class London world of “Maria,” a society figure who responds to the daily challenges of life in ways that show her at once silly and admirably indomitable. Throughout War Phases, Maria modeled a very British kind of unflappability, as well as a sense of fun, whether she was dealing with rationing and food shortages or perching on a torpedo, during her visit aboard a submarine. The illustrations for this volume, by Annie Harriet Fish (1890–1964), show the artist’s admiration for the distinctive black-and-white style of Aubrey Beardsley, who had been the art editor of the Yellow Book, the avant-garde magazine published by John Lane in the mid-1890s. This copy was presented by the author to Thomas A. Edison.