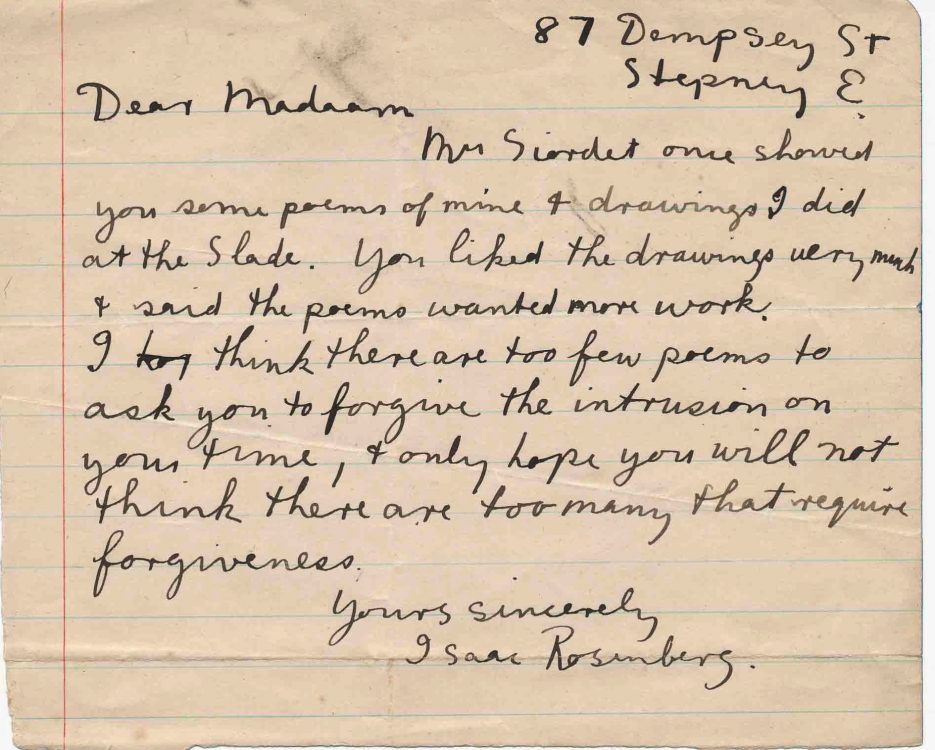

Isaac Rosenberg, 1890–1918

Autograph letter signed to Alice Meynell, [ca. 1915]

That Isaac Rosenberg’s name eventually would be awarded a place in Westminster Abbey, in Poets’ Corner, might have seemed unlikely on several counts. He was a serious portraitist, trained at the Slade School of Fine Art (as he mentions in this letter to Alice Meynell, the Catholic poet), whose gift for writing appeared at first to take a backseat to his devotion to painting. But he was also a Jew of Lithuanian parentage, who grew up in London’s East End slums at a time of virulent anti-Semitism, making him a true long shot for any official honors bestowed by the British nation. Nonetheless, following his service on the battlefields of France and his death in 1918, near the end of the war, he achieved widespread recognition as one of the greatest of the soldier-poets, alongside figures such as Wilfred Owen and Rupert Brooke, for work that included the 1915 volume Youth and the posthumously published “Break of Day in the Trenches,” a poem still widely reprinted today.

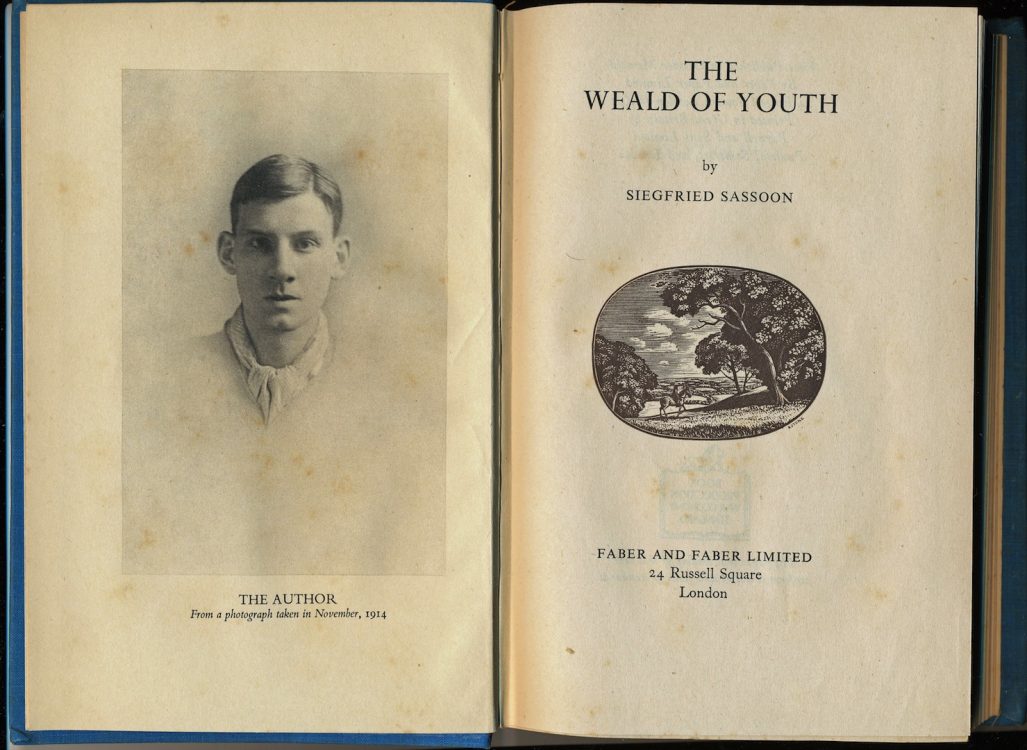

Siegfried Sassoon, 1886–1967

The Weald of Youth

London: Faber & Faber, [1942]

Siegfried Sassoon was among the greatest of the soldier-poets, serving with distinction, but then writing angrily about the war as a nightmare that had to be ended, not as a glorious event. Later, he described the horrors he had encountered in autobiographies that took two different literary forms. The fictionalized “George Sherston” trilogy, which started with The Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man (1928), was published to acclaim, but then was followed by “straight” versions of his experience in The Old Century and Seven More Years (1939), The Weald of Youth (1942), and Siegfried’s Journey (1945). The Weald of Youth described his early interest in poetry and acquaintance with figures such as Edmund Gosse and George Moore, but ended just as the war began in August 1914. Sassoon inscribed this copy to "Max, with the love and admiration of the Author. SS October 15th-1942" and added a long quotation from Henry James, together with a hand-drawn “bookplate” for the satirist Max Beerbohm that facetiously ennobled him as “Viscount Villino-Chiaro.” Beerbohm had corrected the proofs for this book and was the dedicatee of its predecessor, The Old Century and Seven More Years.

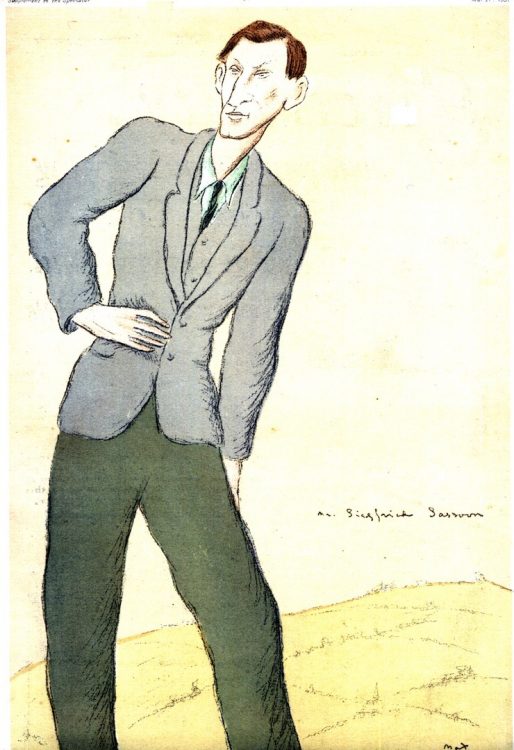

Sir Max Beerbohm, 1872–1956

Mr. Siegfried Sassoon

Pencil and watercolor on paper, 1931

Max Beerbohm and Siegfried Sassoon met in the summer of 1916, at the home of the Victorian critic and author of the memoir Father and Son, Edmund Gosse. (Sassoon would later write about Gosse in his own memoir, The Weald of Youth.) Having distinguished himself in battle on the Western Front and received the Military Cross for valor, Sassoon was back in England, recovering from a bout of fever and keeping up his links with the literary world, at the time of this first encounter with Beerbohm. A warm friendship developed between the great ironist and caricaturist of the 1890s, who looked askance at the brutality of the war, and Sassoon, an aspiring poet who had also come to doubt the rightness of mass slaughter. This drawing, which Beerbohm produced for the Spectator, shows Sassoon long after the war, when he had become famous for the first two volumes of his “George Sherston” trilogy and been awarded several major prizes for Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man, in particular.

Mabel Dearmer, 1872–1915

Letters from a Field Hospital, with a Memoir of the Author by Stephen Gwynn

London: Macmillan and Co., 1915

Although she was a gifted British illustrator and poster artist, who was influenced by the work of Aubrey Beardsley and belonged to the Yellow Book circle in the 1890s, Mabel Dearmer was never a Decadent. She was instead a socialist dedicated to the “uplift” of the poor, especially through the arts (as was Percy Dearmer, her Anglican clergyman husband). After the turn of the century, she became well known for her plays for children. When war broke out in 1914, she engaged in relief work for Belgian refugees and, despite her pacifist objections to battle, chaired the publicity department of the Women’s Emergency Corps. She then made the fateful—and ultimately fatal—decision to accompany her husband to Serbia in April 1915, after he was appointed chaplain to the British army there. While working as a volunteer in a field hospital, she contracted typhoid fever and died in July 1915, though not before writing to her friend Stephen Gwynn a series of letters that described in frank and vivid terms the conditions she had witnessed near the frontlines. Those letters were collected and published shortly after her death—one of the early firsthand accounts of the war from a woman’s perspective.

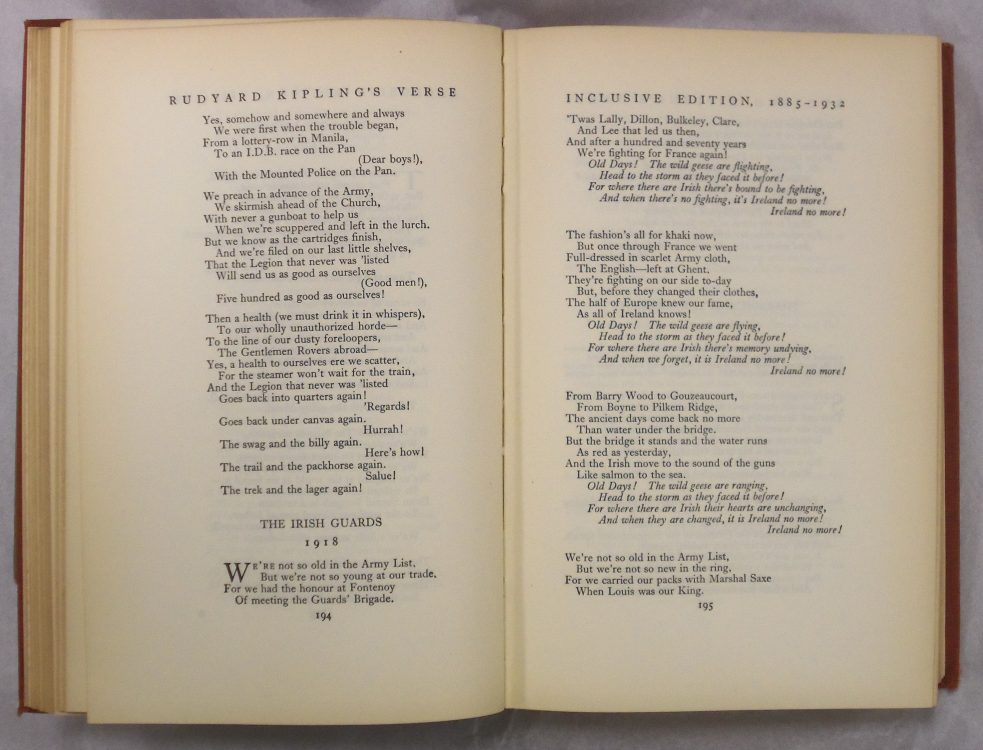

Rudyard Kipling, 1865–1936

Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: Inclusive Edition

London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1933

Nearly a hundred pages of Rudyard Kipling’s Verse is made up of poems concerning the 1914–1918 conflict, during which Kipling’s beloved son John was killed in action. This was the artist and writer Max Beerbohm’s copy, in which he has inserted in manuscript an amusing addition to Kipling’s memorial to Edward VII, “The Dead King.” If Beerbohm felt little reverence in general for this self-indulgent and undisciplined British monarch, he had even less respect for the poet who had celebrated him. Although Beerbohm admitted reluctantly that Kipling was a “genius,” he also loathed him as a “schoolboy, a bounder, and a brute,” who had misused his talents to fuel British imperialism, jingoism, and the “love of blood.”

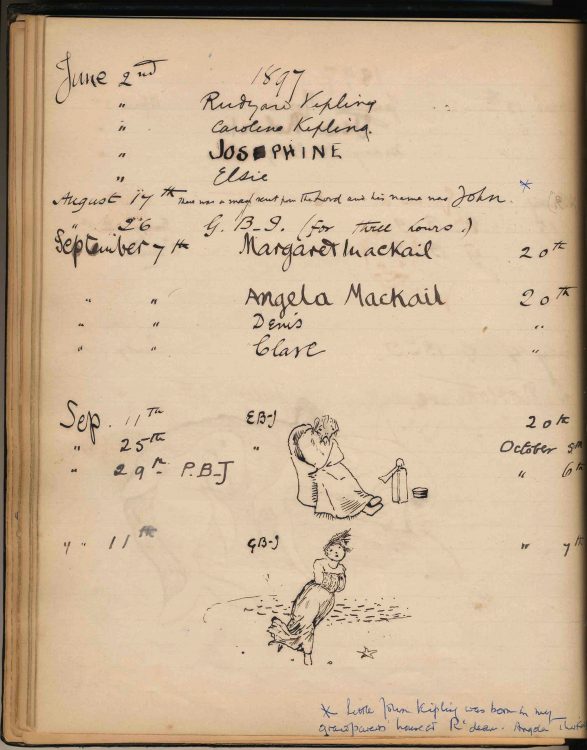

Edward Burne-Jones, 1833–1898

Visitors Book for North End House, Rottingdean

Autograph manuscript, 1881–1898

This book records the visits of family and friends to the Sussex holiday home of the Pre-Raphaelite painter, Edward Burne-Jones, and his wife, Georgiana. Embellished with caricatures (and self-caricatures) by the artist, it contains the signatures of such figures as the poet and artist William Morris and his wife, Jane; the playwright J. M. Barrie; and Stanley Baldwin, the future prime minister. Of particular interest are the entries for August 1897, which refer to the presence of the Kipling family at The Elms, their house nearby in Rottingdean. On 17 August, Kipling notes the birth of his son, John, who would grow up to have his life cut short by the war. Although John, who was both underage and afflicted with poor vision, was rejected for military service, Kipling pulled strings to secure him a Commission. After John was grievously injured and reported missing in action in September 1915, during the Battle of Loos, his stricken parents went to France to search for him, but were unable to find and recover his body. Kipling was devastated, writing not only the poem “My Boy Jack,” but The Irish Guards in the Great War (1923), a history of John’s regiment.

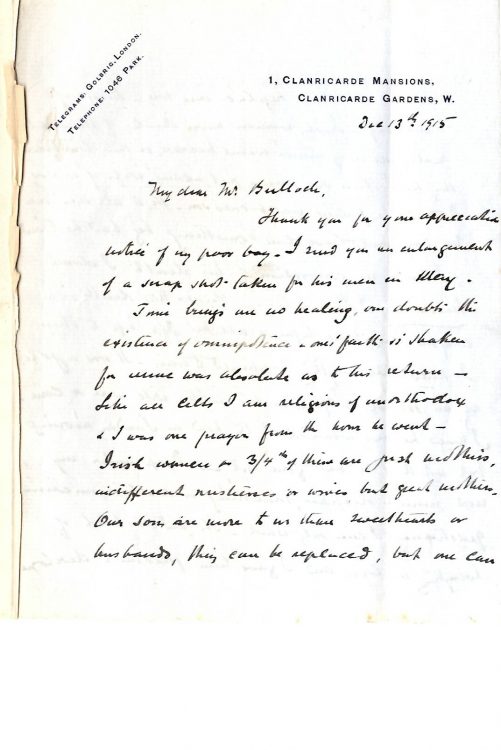

George Egerton, 1859–1945

Autograph letter signed to J. M. Bulloch

In this painful letter, Mary Chavelita Dunne—who used the pen-name “George Egerton” for her books of short stories and plays—wrote frankly, as she put it, from “Celt to Celt” to the Scottish journalist and editor, J. M. Bulloch. Although she had been living in England for many years and was now married to an Englishman, the theatrical agent Reginald Golding Bright, she still identified with her Irish roots and felt that her suffering as the mother of a young soldier killed in France was different from, and even deeper than, the feelings of British women who experienced similar losses. The son who died in battle, George Clairmonte, was her only child (by her first husband, who had deserted her not long after his birth). Throughout her notorious career in the 1890s as a “New Woman” writer of fiction, most of it published by John Lane and his Bodley Head firm, she had argued for sexual freedom for women, but had also insisted that a woman’s deepest natural impulse was the drive to experience maternity.

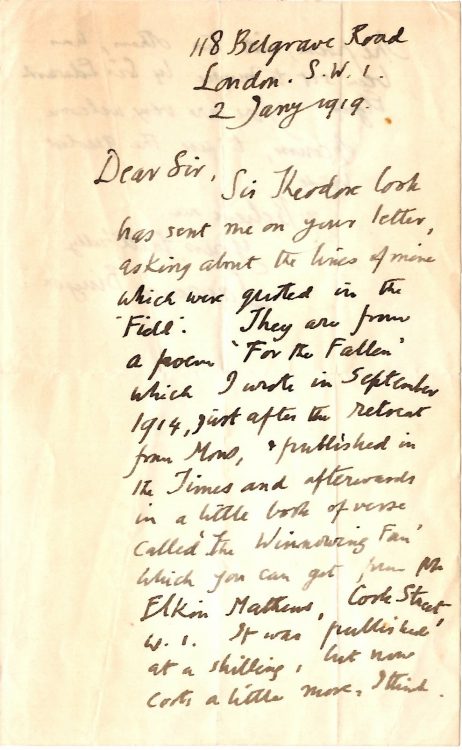

Laurence Binyon, 1869–1943

Autograph letter to “Dear Sir,” 2 January 1919

“They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning,

We will remember them.”

These often-quoted lines are from one of the most famous poems inspired by the First World War—“For the Fallen” by Laurence Binyon (a work later set to music by Sir Edward Elgar). Although Binyon was too old for active service, he saw the casualties of the war at firsthand while volunteering as a hospital orderly. In this letter to an unnamed admirer, he talks of the composition of this poem and also refers to one of his later volumes, which was published by Elkin Mathews, who had been co-founder with John Lane of the Bodley Head firm: “‘For the Fallen’ which I wrote in September 1914, just after the retreat from Mons, & published in The Times and afterwards in a little book of verse called The Winnowing-Fan which you can get from Mr. Elkin Mathews, Cork St., W. 1. It was published at a shilling but now costs a little more, I think.”