Shane Leslie, 1885-1971

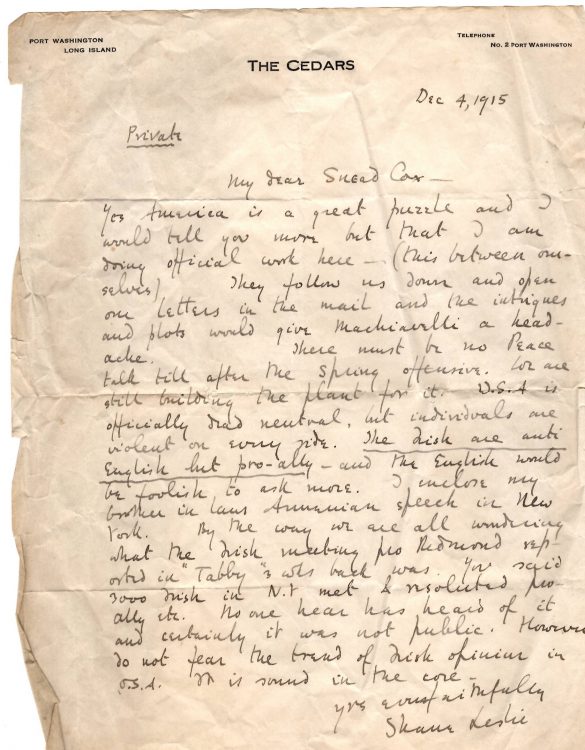

Autograph letter signed to Alice Meynell, 4 December 1915

Sir John Leslie—an English aristocrat with links to the United States on his mother’s side—came to identify so strongly, while a young man, with Irish nationalist causes that he gave up his rights to his family estate and began calling himself “Shane.” During the war, he served in the British Ambulance Corps, but then took up service of a different kind and worked at the British embassy in Washington on behalf of two causes: urging the U. S. to go to war against Germany, and promoting a rapprochement between Irish Americans and the British government, A convert to Roman Catholicism, he was friends with the English Catholic poet Alice Meynell. Shortly after arriving in New York, he wrote to her about his efforts with the Irish community: “The Irish are anti-English but pro-ally – and the English would be foolish to ask more.”

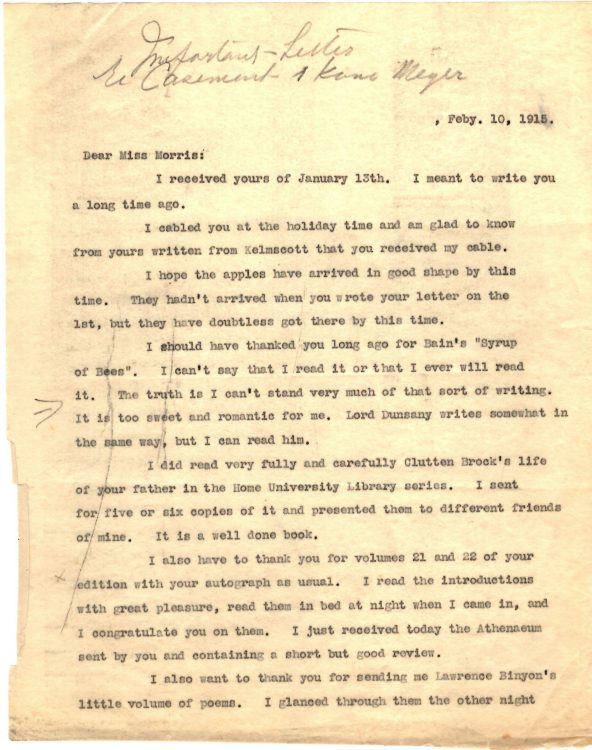

John Quinn,1870–1924

Typewritten letter signed to May Morris, 10 February 1915

One of the great art patrons art of his time, the brilliant and successful lawyer John Quinn was also a major book collector, keenly interested in Irish writers such as Oscar Wilde, W. B. Yeats, and James Joyce. (He defended Ulysses and owned the manuscript of the novel, now in the Rosenbach Museum and Library). Quinn’s lovers included May Morris—designer, needlework artist, and the daughter of the socialist artist and writer, William Morris—whom he met when she came to the United States on a lecture tour in 1909–10. While their affair was short-lived, Quinn and Morris engaged in a long correspondence that continued until his death. Quinn held strong political opinions and supported Irish independence. His views on racial and ethnic minorities, however, were disconcerting to say the least. Here, in a letter dictated to one of his secretaries, he indulges in a lengthy discussion of current events, including a diatribe against Germany and an attack on so-called Jewish profiteering from the war.

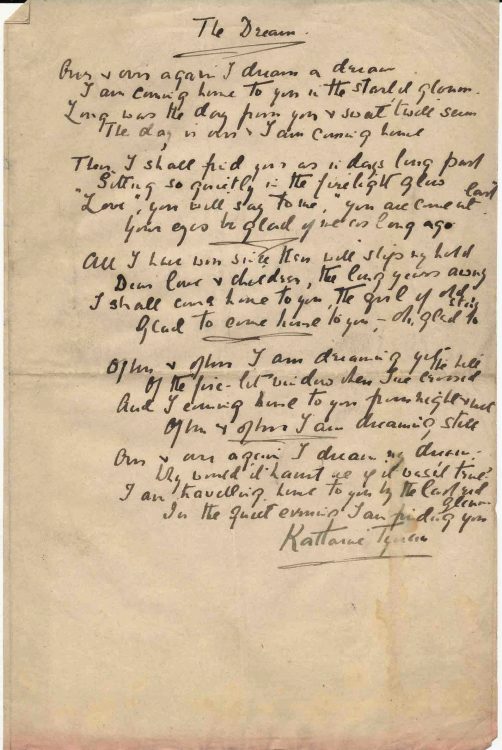

Katherine Tynan, 1859–1931

The Dream

Autograph manuscript signed, [1917–1918]

Of the women writers of the Irish Renaissance, the Dublin-born Katharine Tynan was among the most prolific, turning out prodigious quantities of fiction, poetry, and journalism, both before and after her marriage in 1898 to Henry Hinkson and her move to London. A close friend and literary associate of William Butler Yeats, she was also part of the social circle of Lady Wilde, the poet known as “Speranza” (and the mother of Oscar Wilde), as she reported in one of her volumes of memoirs. During the war years, she again lived in Ireland, while two of her sons were serving overseas. Tynan’s volume Herb o' Grace: Poems in War- Time (1918) contained the lyric “The Dream,” which was subtitled “(For My Father).” In it, the speaker dreams of turning back time—coming home again as a young girl and reuniting with her father. For readers who were weary of war privations and who had suffered the loss of loved ones, such an expression of nostalgic, impossible yearning for a happy past must have been almost unbearably poignant. (This manuscript version of the poem has a different text and includes an unpublished final stanza.)

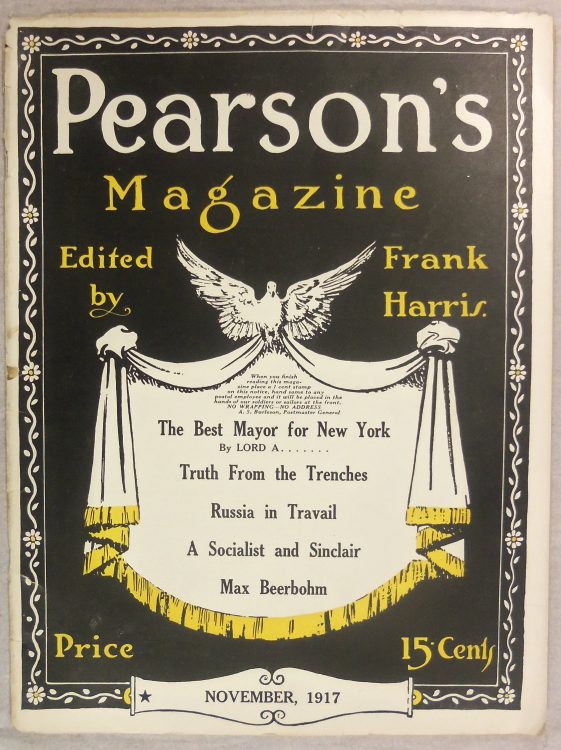

Pearson’s Magazine, November 1917

New York: Pearson publishing co., 1917

No longer welcome in England, both for his financial misdeeds and his support of the Germans, Frank Harris, the notorious Irish-born journalist, womanizer, and disciple of the late Oscar Wilde, came to New York to edit Pearson’s. He turned the popular weekly into an anti-British isolationist journal, which landed him in further trouble, especially after the United States entered the war in April 1917. In Pearson’s pages, political opinions shared space with literary content, including Harris’s own reminiscences of famous people (eventually collected into several volumes of Contemporary Portraits)and his articles about Shakespeare, with whom he was obsessed.In this issue appears “The trees again and Max,” an error-filled piece about Max Beerbohm, illustrated with a caricature by Beerbohm that shows him conversing with Harris across a lunch table. Beerbohm said of Harris that he sometimes told the truth, but only “when his imagination failed.”

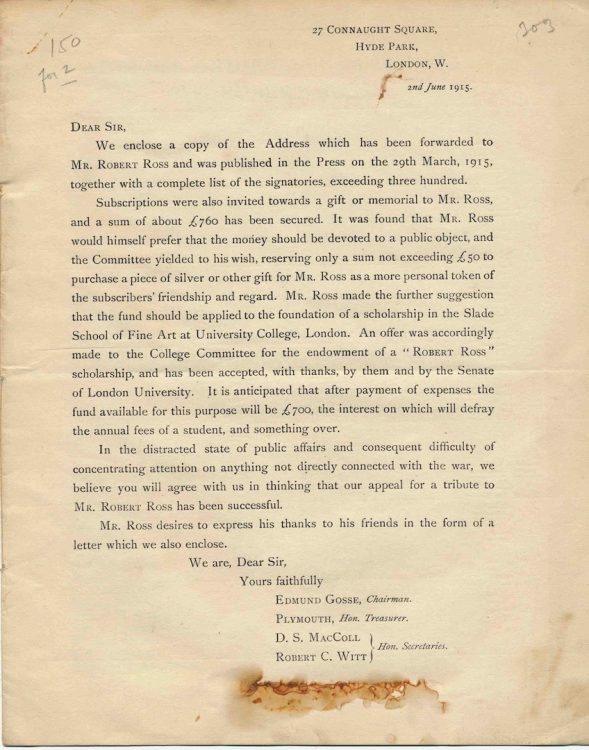

Letter to donors to the Robert Ross subscription

London: [Chiswick Press], 2 June 1915

This printed circular was sent to those who had contributed funds for a testimonial to honor Robert Ross. Widely believed to have been Oscar Wilde’s first male lover (although Molly Whittington-Egan has suggested that this designation rightly belongs to the painter Frank Miles), Ross had staunchly remained close to Wilde until the latter’s death in 1900, and then continued to serve as his executor and as editor of his published works. For many, indeed, he represented the Keeper of the Flame (as opposed to Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s more famous romantic partner, who publicly repudiated both Wilde and his literary influence after the turn of the century). Raising money on behalf of an individual, however admirable, was no easy matter in 1915, as this letter attests, with its reference to the “distracted state of public affairs and consequent difficult of concentrating on anything not directly connected with the war.” Most of the £760 raised was used to fund a scholarship at the Slade School of Fine Art.

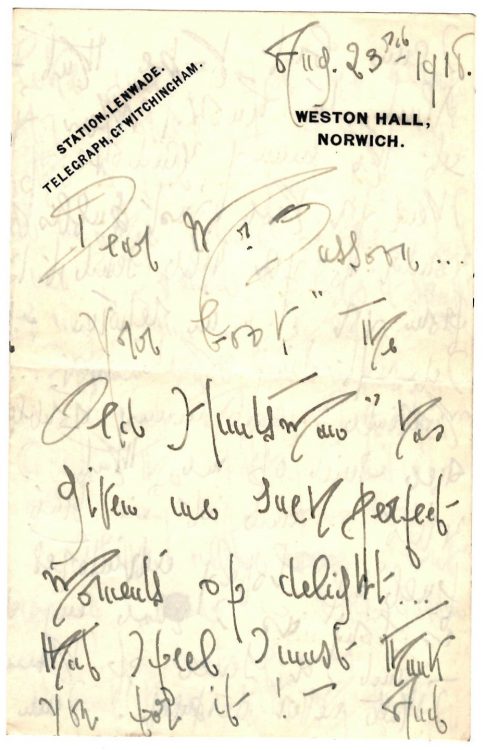

Olive Custance, 1874–1944

Autograph letter to Siegfried Sassoon, 23 August 1918

Among turn-of-the-century British women poets, Olive Custance had perhaps the most surprising romantic history. Not only was she a lover of women (including the American expatriate poet, Natalie Barney), but she married the poet Lord Alfred Douglas, who had so famously been associated with Oscar Wilde in the 1890s, and whose father, the Marquess of Queensberry, was behind Wilde’s 1895 conviction and imprisonment for “gross indecency” with men. Her own father was a well-to-do military officer, and she had been raised in the world of the landed gentry with which the soldier-poet Siegfried Sassoon, too, was familiar. Here she writes to Sassoon, “Your book The Old Huntsman has given me such perfect moments of delight that I feel I must thank you for it.”

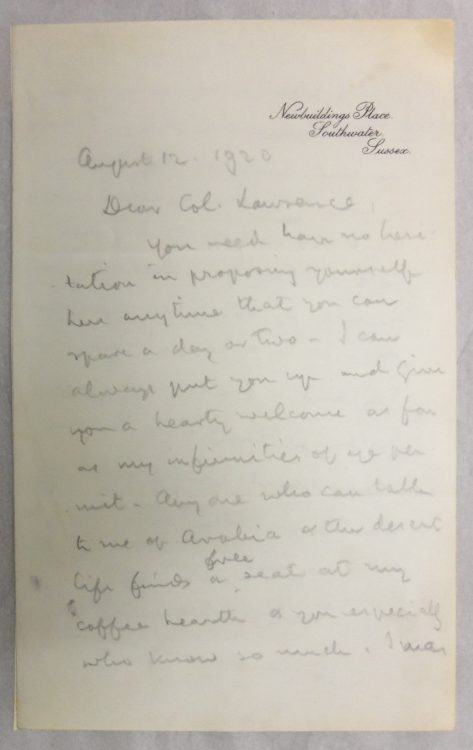

Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, 1840–1922

Autograph letter signed to T. E. Lawrence. 12 August 1920

Before there was the romantic figure of “Lawrence of Arabia,” there was the equally romantic figure of Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, an anti-imperialist English Catholic poet and diplomat who came from a distinguished background (and who married a descendant of Lord Byron), but whose real passion was for Arab cultures, as well as for breeding Arabian horses. Just a few years after the war in which T. E. Lawrence had played such a vital part in the Arab uprising against the Ottoman Empire, Blunt writes to him and invites his new acquaintance to visit, saying that “anyone who can talk to me of Arabia and the desert life finds ever a seat at my . . . hearth.”