Ellen Terry and her cat, Boo-Boo

Photograph, [ca. 1918–1920]

Inscribed by Terry in 1922

The great Victorian actress Ellen Terry (1847–1928) was a survivor. Throughout her long career on the stage, she adapted to many sorts of challenges and changes. When war was declared in 1914, she was in the midst of a world tour, with a one-woman show of monologues by her favorite Shakespearean heroines. She quickly involved herself in charitable work for war relief and, on 8 December, performed one of Portia’s speeches from The Merchant of Venice at a gala benefit in New York’s Strand Theatre. Among the other theatrical luminaries onstage with her was a fellow Briton, Mrs. Patrick Campbell; Broadway stars, such as William Gillette and Ethel Barrymore; and even the vaudeville comedy team of Weber and Fields.

Corinne Roosevelt Robinson, 1861–1933

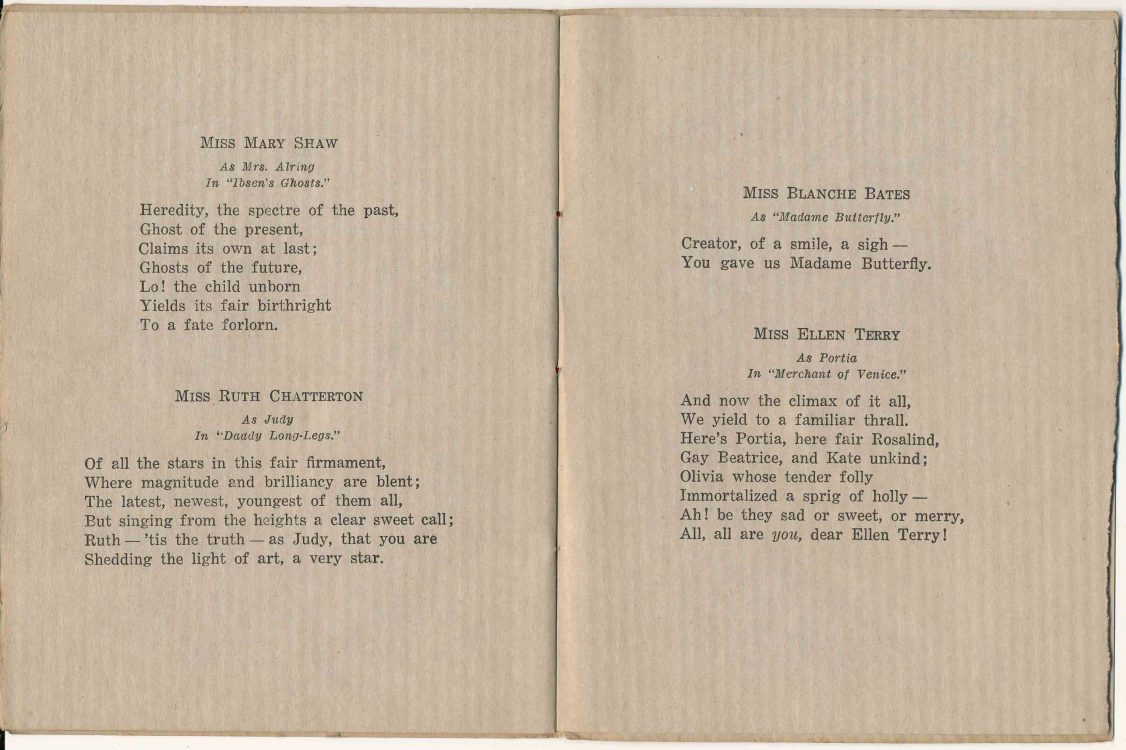

Verses, by Mrs. Douglas Robinson; Read by Comedy and Tragedy at the Official Benefit for the Relief of Belgian women and Children, December 8th, Strand Theatre, New York

[New York, 1914]

One unusual feature of the gala war benefit held at New York’s Strand Theatre on December 8, 1914 was the reading of a set of short poems, each dedicated to a particular actor, composed by Connie Roosevelt Robinson, (sister of Theodore Roosevelt). This rare special printing of Robinson’s verses was likely distributed to the audience members, many of whom no doubt lost their copies during the elaborate tea-dance that followed the matinee.

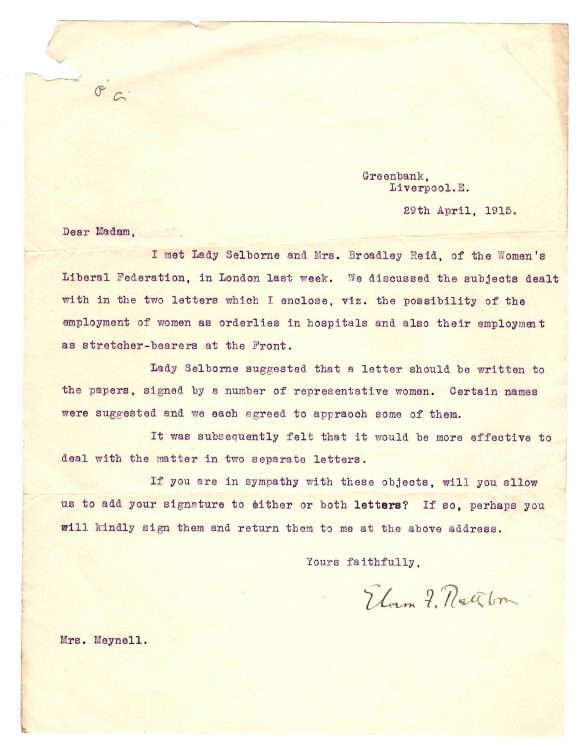

Eleanor Florence Rathbone, 1872–1946

Typewritten letter signed to Alice Meynell, 29 April 1915

Eleanor Rathbone, who came from a prominent Merseyside family, studied at Oxford as a young woman in the 1890s, before returning to Liverpool. There, she pursued local politics as a member of the City Council, campaigning tirelessly for improvements to the lives of the laboring poor. But the cause dearest to her heart was women’s rights. She was one of the most important feminist activists of the early decades of the century and, after the war, headed the National Union of Suffrage Societies. During the war, however, she became known for her leadership of the Liverpool branch of the Soldiers and Sailors Family Association, which provided financial and other kinds of support to women and children left behind on the homefront. In this letter, she asks the poet Alice Meynell for permission to use her name in promoting a different cause— “the employment of women in hospitals and also their employment as stretcher-bearers at the Front.”

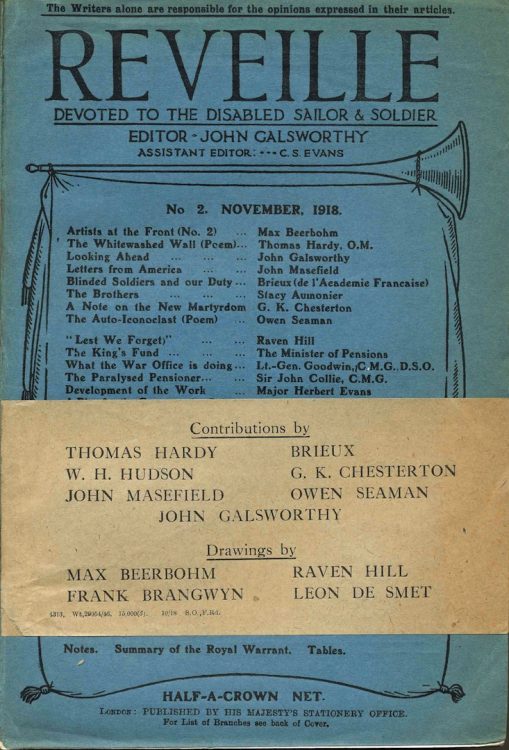

Reveille: Devoted to the Disabled Sailor & Soldier, No. 2, November 1918

London: H. M. S. O., 1918

John Galsworthy, famous for his plays and for novels about the Forsyte family, gathered together work from friends and associates for this official periodical, which ran to three numbers from August 1918 to February 1919. Each issue boasted a full-color caricature by Max Beerbohm, virtually his only published “war work” and unusual in that the subjects portrayed “artists at the front.” The magazine’s roster also included Rudyard Kipling, along with J. M. Barrie, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, and the young Enid Bagnold (who had written in 1917 about her nursing service as a V.A.D. in A Diary Without Dates). Much of the content, including essays by military officers (among them the King of Portugal), was meant to uplift the spirit of “the disabled sailor & soldier” and in some cases actually provided practical advice for those missing a limb or eye. The advertisers offered painkillers (“contains no cocaine”), artificial legs, and the “Purostat,” a “universal apparatus” which was alleged to have many medical uses.

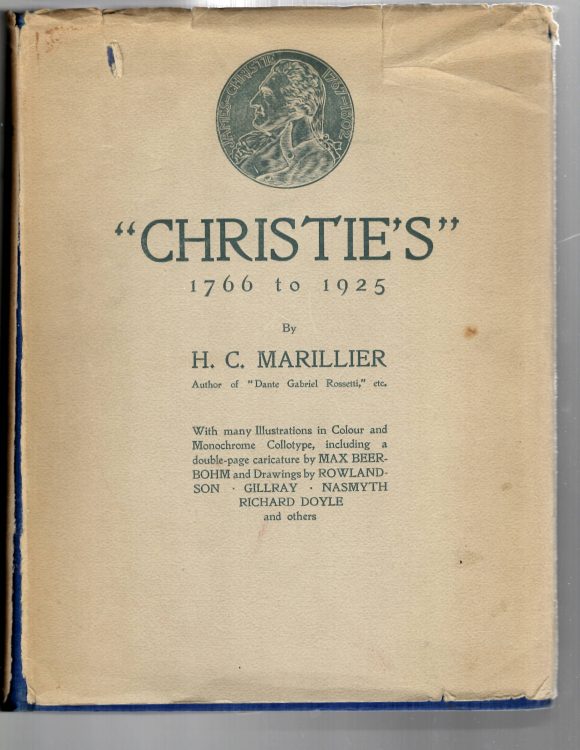

H. C. (Henry Currie) Marillier, 1865–1951

“Christie’s” 1766–1925

London: Constable and Company, Ltd., 1926

Benefit auctions, along with books sold by subscription and theatrical performances held for charity, proved popular ways of raising money to support a variety of causes related to the war. The four sales organized at Christie’s in London to benefit the Red Cross Society and the Order of the Hospital of St. John not only proved lucrative, bringing in more than £450,000, but served as fashionable social events, allowing the well-to-do to feel virtuous, while still enjoying themselves and flaunting their success publicly. This caricature by Max Beerbohm (the original was offered for sale in the 1918 auction) depicts the glittering array of celebrities and millionaires—ranging from Lord Curzon, Sir Ernest Cassel, and Lady Windsor, to the playwright J. M. Barrie, the artist William Nicholson, and the writer Edmund Gosse— who donated or bid on valuable items.

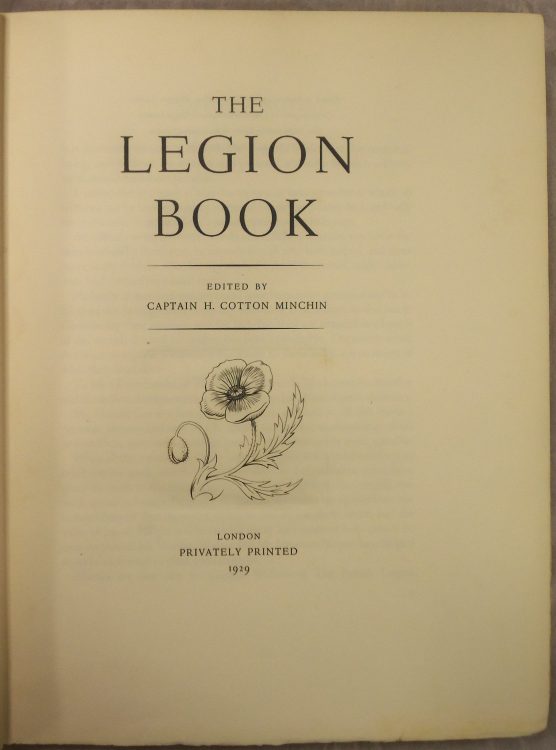

H. Cotter Minchin, ed.

The Legion Book, Edited by Captain H. Cotton Minchin

London: Privately printed, 1929

Elaborately produced anthologies with contributions from celebrated writers and artists were a common method of fund-raising for the numerous charities that were started during the war and, after it, for the benefit of veterans. Often issued in a variety of editions—the smaller the printing, the higher the price—the books were, and remain, highly sought after. The most famous was Edith Wharton’s The Book of the Homeless (1916), but The Legion Book, published in 1929 to aid the British Legion, which had been founded in 1921 to aid ex-servicemen, is almost as remarkable. The authors and illustrators included such luminaries as Rudyard Kipling, Rebecca West, Winston Churchill, P. G. Wodehouse, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, John Singer Sargent, Jacob Epstein, Max Beerbohm, and John Galsworthy. The book is dedicated to the Legion’s patron, the Prince of Wales, later Edward VIII. Many of the contributions refer directly to the First World War. This was Max Beerbohm’s copy, with his illustration, Prime Ministers in my day—and tremendous luminaries in theirs, in ink and watercolor, with an annotation, “Not a bad design, but a woefully dull and timid drawing—now slightly improved by pen and ink. 1930. Max.”