For much of his career Whistler challenged the conventions of Victorian culture as a central figure of the Aesthetic Movement. Founded on the philosophy of “art for art’s sake,” Aestheticism emphasized the pursuit of beauty in art over any moral or narrative function. The movement was not limited to fine art but permeated all areas of British life, from music and literature to interior design and fashion. Whistler embodied the values of Aestheticism in his art and personal style and also advocated for them in his 1885 manifesto, the “Ten O’Clock” lecture.

Whistler established important friendships with other proponents of the Aesthetic Movement, although these relationships often devolved into feuds, including a prolonged public battle of wits with the Irish writer Oscar Wilde. As the most outspoken public champions of Aestheticism, Wilde and Whistler also became the subject of many critiques of the movement, from George Du Maurier’s satirical cartoons in Punch and his later bestselling novel, Trilby, to Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera Patience. Whistler remained a lifelong advocate for the views of the Aesthetic Movement, inspiring younger artists including his wife, Beatrix Whistler, and the illustrator Aubrey Beardsley.

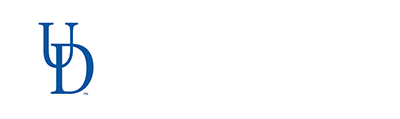

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

La Robe Rouge, 1894

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Beatrix Whistler (née Beatrice Philip) was an artist and designer who met Whistler through her first husband, the architect Edward William Godwin. In La Robe Rouge, she reclines in an armchair in the drawing room of their Parisian house. The original drawing was done on thin paper, which was sent to Whistler’s printer, Thomas R. Way, who transferred the image onto a lithographic stone for printing. It was one of many portraits Whistler made of his wife in the early 1890s as they traveled between London and Paris seeking improvement for her poor health.

Beatrix Whistler (British, 1857–1896)

Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1894

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

For many years scholars and collectors believed this lithograph was by James McNeill Whistler, but recent research has convincingly suggested that it was actually drawn by his wife Beatrix. Her print is based on a portrait of the French aristocrat, dandy, collector, and arch-aesthete Count Robert de Montesquiou, painted by her husband in 1892 (The Frick Collection). Both James and Beatrix set to work on a lithographic version of the portrait for a French art journal in the summer of 1894. However, neither artist was satisfied with the results, so the portraits were never published. This proof print is a rare example of Beatrix Whistler’s work held outside of the Whistler collection at the University of Glasgow.

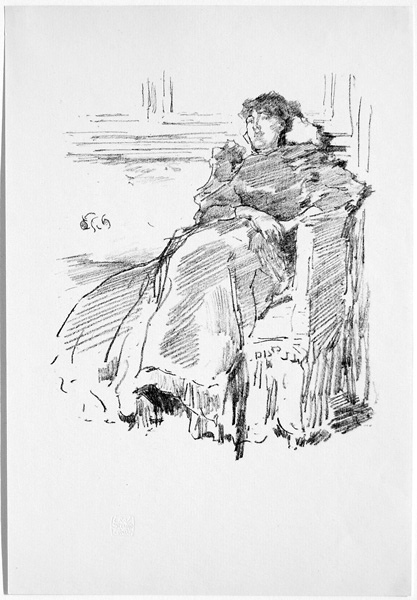

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Thames, 1896

lithotint with scraping on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

One of Whistler’s most complex and evocative nocturnes, The Thames was also the last image he created while living at London’s Savoy Hotel with his wife Beatrix in early 1896. Many of Whistler’s lithographs from this period were printed using transfer paper, but he drew this image directly on a stone, which his printers had prepared and delivered to the hotel. Whistler worked on the stone on his balcony for several weeks, eventually capturing the effects of the silvery mist and delicate lights of the Thames at dusk. At this point Beatrix was quite ill with cancer, but when possible her bed was moved near the windows so that she too could take in the view of the river and the city. She died in May 1896.

Whistler and Wilde

It was almost inevitable that Whistler's friendship with writer Oscar Wilde would end with enmity. The men were too much alike: wits, dandies, self-promoters, and outsiders—one American, one Irish—clamoring for attention. A leading proponent of the Aesthetic Movement, Wilde is best known for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), his comic play The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), and the 1895 trial that led to his imprisonment for homosexuality.

When Wilde met Whistler around 1879, he quickly fashioned himself as the artist’s disciple. As his popularity eclipsed Whistler’s in the 1880s, a battle of wits began to play out in private and in the press. Whistler grew to resent the ways Wilde had adopted not only his ideas, but also elements of his speech and style. Once, after hearing Whistler make a clever remark at a party, Wilde exclaimed that he wished that he had said it. Whistler retorted “You will, Oscar, you will.” Despite their ultimate falling out, Whistler and Wilde’s repartee helped to shape the public’s perception of both men.

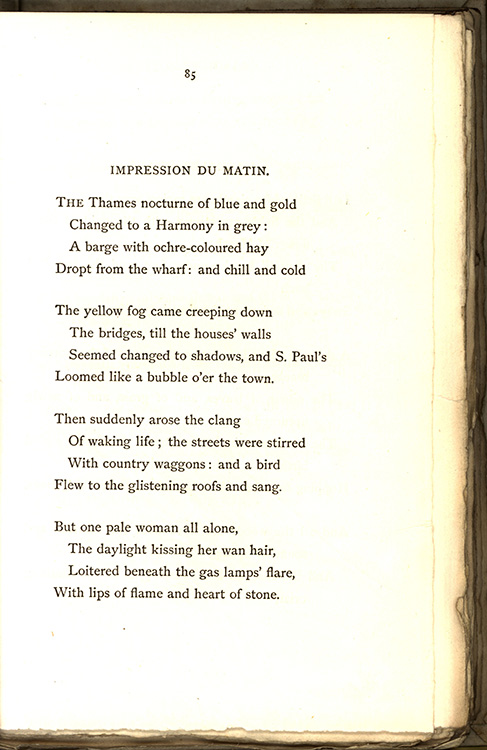

Oscar Wilde (Irish, 1854–1900)

Poems. London: David Bogue, 1881

Author's presentation copy to Violet Fane, with original manuscript poem

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Oscar Wilde's volume of verse reflects the significance of writers and artists associated with Aestheticism, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, to his writing. Wilde’s admiration for Whistler is apparent in the poem “Impression du Matin.” The opening lines evoke the combination of music and color Whistler sought to convey in his work:

The Thames nocturne of blue and gold

Changed to a Harmony in grey

Wilde gave this copy of Poems to the writer Violet Fane (pseudonym of Mary Singleton), who was also a friend of Whistler.

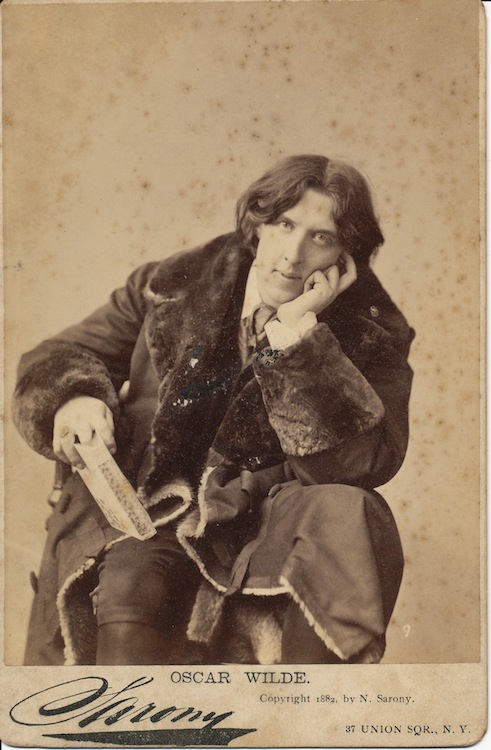

Napoleon Sarony (American, b. Canada, 1821–1896)

Oscar Wilde, 1882

albumen cabinet card

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In January 1882, shortly after arriving in America for a year-long lecture tour, Oscar Wilde posed for a series of photographs in the New York studio of Napoleon Sarony. The portraits were used to advertise his lectures, which were intended to promote Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera Patience. Like Whistler, Wilde purposefully shaped his image by adopting distinctive dress. His velvet jacket, knee breeches, and silk stockings quickly became fodder for caricatures and were adopted by his admirers. In this photograph he is holding a volume of his first book, Poems (1881). The influence of Whistler was equally evident in the substance of Wilde’s lectures, which addressed art, design, and Aesthetic theory.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888

Author’s presentation copy to Beatrix Whistler, accompanied by a printed invitation to the lecture

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

On February 20, 1885, Whistler delivered his “Ten O’Clock” lecture, an hour-long evening talk in London later published in this volume. He carefully orchestrated the event, from the unusual time to the composition of the audience, which included fashionable artists, patrons, and writers. Whistler challenged contemporary ideas about art, arguing that it should not seek to copy nature, have literary meaning, or serve a social purpose. The talk was also a rebuke to Oscar Wilde, who watched from the third row. Whistler felt Wilde had plagiarized his artistic theories. Wilde responded to the lecture with critical articles in the Pall Mall Gazette, setting off a series of acerbic exchanges in the press that led to further estrangement.

Whistler inscribed this copy of the published lecture to his wife Beatrix using her pet name “To my ‘luck’” and signed it with his signature butterfly.

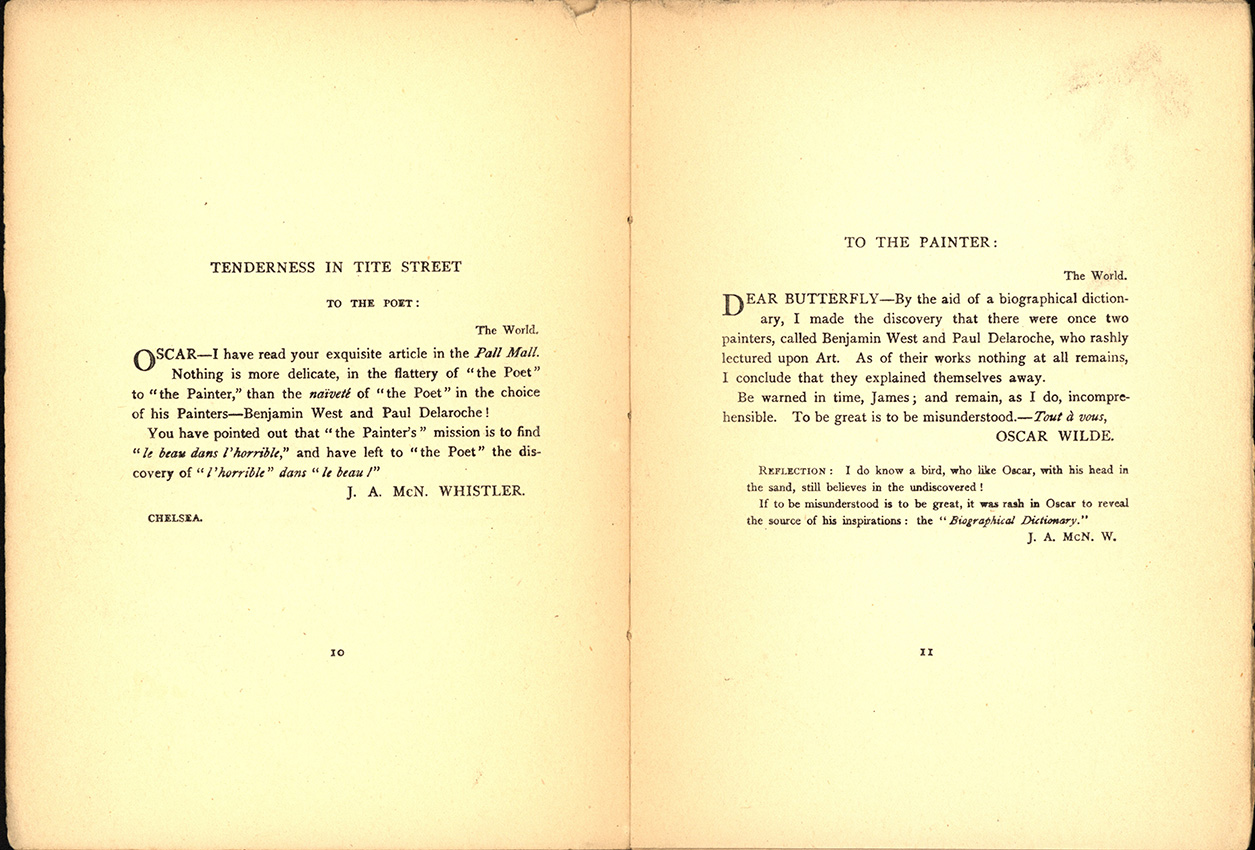

Oscar Wilde (Irish, 1854–1900)

Wilde v. Whistler: Being an Acrimonious Correspondence on Art between Oscar Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. London: Privately Printed, 1906

Special Collections

Based on the format of Whistler’s pamphlets, Wilde v. Whistler offers insight into the notorious feud between the writer and the artist. Wilde’s canny publisher, Leonard Smithers, produced this small volume as a rare collector’s item, taking advantage of the burgeoning market for both Wilde and Whistler after their deaths. The contents were nothing new, comprising letters and reviews published in London newspapers between 1885 and 1890. The book begins with Wilde's negative review of Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” lecture and chronicles their ongoing clashes in the press.

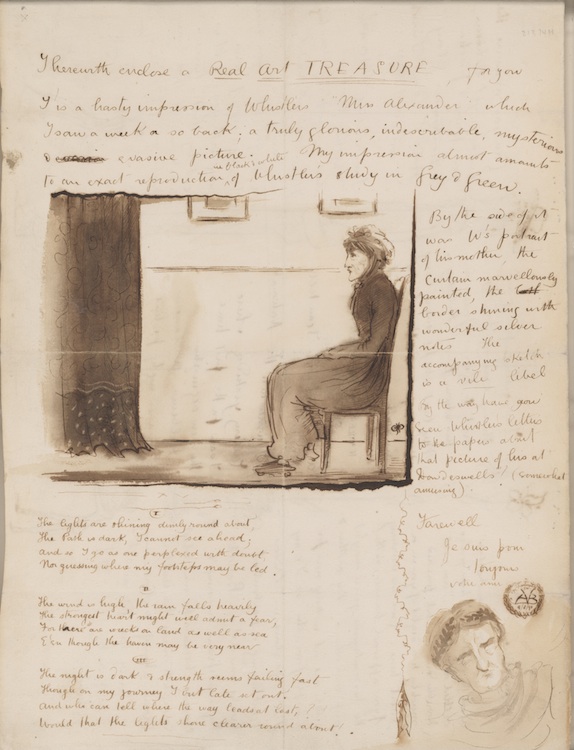

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872–1898)

Autograph letter signed to G. F. Scotson-Clark, 9 August 1891

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Aubrey Beardsley was a leading English illustrator of the 1890s and a central figure in the Decadent Movement. He is best known for his striking illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play, Salome. In this letter to a former school friend, the nineteen-year-old artist indicates his great admiration for Whistler and the Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother. He had recently seen the painting at the Society of Portrait Painters exhibition in London. Beardsley describes Whistler’s work as “a truly glorious, indescribable, mysterious & evasive picture…the curtain marvellously painted, the border shining with wonderful silver notes.” Beardsley includes a sketch of himself in the same pose as the seated figure of Whistler’s mother, going as far as to sign it with an imitation of Whistler’s butterfly.

Harry Furniss (British, 1854–1925)

Sketches of “Patience” at the Opera Comique, from Punch, June 17, 1881

hand-colored lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

This print by illustrator Harry Furniss records scenes from the opening night of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera, Patience, which satirized the Aesthetic Movement. Published in the popular magazine Punch, the lithograph includes images of the actor George Grossmith in the role of the “fleshly” poet Reginald Bunthorne, who sings:

Am I alone, And unobserved? I am!

Then let me own I'm an aesthetic sham!

With his monocle and dark curly hair with a white streak, Bunthorne’s costume clearly references Whistler, but his knee breeches are reminiscent of Wilde. The show was a commercial success and was one of the few satirical depictions of their identities that both Whistler and Wilde enjoyed. Patience helped ensure that the two men were tied together in the public eye as exponents of Aestheticism.

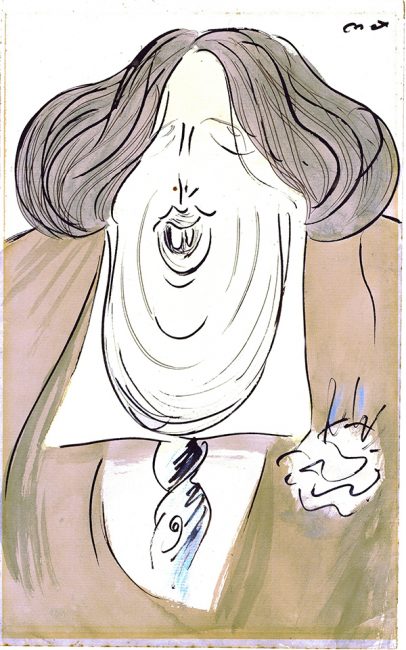

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Oscar Wilde, late 1890s

pencil and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The celebrated caricaturist Max Beerbohm depicted Oscar Wilde repeatedly over the course of his career, capturing the controversial writer’s evolving public image and physical appearance. Although Beerbohm knew and greatly admired Wilde, his caricatures often cruelly exaggerated Wilde’s features and emphasized his increasingly corpulent body. When this caricature was produced in the late 1890s, Wilde had reached the height of fame and success with his plays and had met a swift downfall following his conviction for “gross indecency.”

Although their friendship was over, Whistler followed the legal proceedings and found the prison sentence—two years of hard labor—too harsh.

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Maudle on the Choice of a Profession, 1881

ink on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Illustrator and author, George Du Maurier, was a long-term contributor to the satirical magazine Punch, where his drawings critiqued Victorian society. Du Maurier helped to create an interest in Aestheticism through his mocking cartoons, many of which featured the characters Maudle and Postlethwaite, who resembled Wilde and Whistler. In this drawing Maudle is shown leaning in to speak to a woman at a fashionable event. The caption clarifies that the Wilde-like figure is arguing that existing beautifully is occupation enough for a young man, an exaggeration of Aesthetic values:

Maudle: “How consummately lovely your son is, Mrs. Brown!”

Mrs. B (a Philistine from the country): “What? He's a nice, manly boy, if you mean that Mr. Maudle. He has just left school you know and wishes to be an artist.”

M.: “Why should he be an artist?”

Mrs. B.: “Well, he must be something?”

M.: “Why should he be anything -- why not let him remain for ever content to exist Beautifully!” (Mrs. B. determines that at all events her son shall not study art under Maudle.)

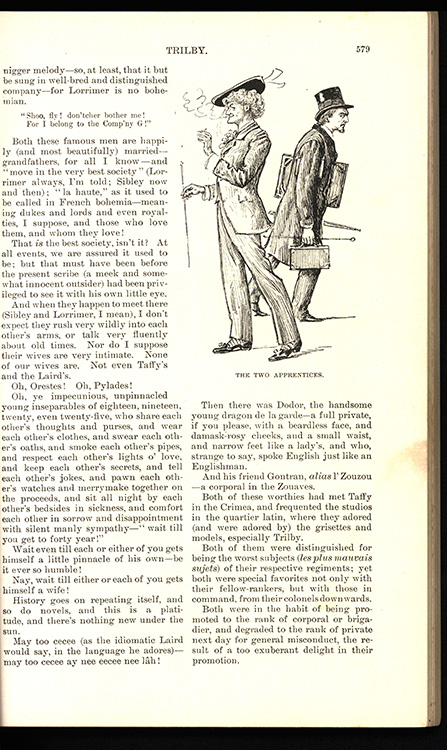

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Trilby, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1894

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Trilby was one of the most popular novels of the Victorian era. Set in Paris of the 1850s, it was based on George Du Maurier’s experiences when he and Whistler were students in the studio of painter Charles Gleyre. By 1894, when the story first appeared in installments in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, the once close relationship between Whistler and Du Maurier had grown distant. Whistler was outraged to discover an unflattering and thinly veiled portrait of himself—pictorial as well as textual—in the story. The character Joe Sibley, described as a lazy, pompous, and eccentric American art student, was easily identifiable. Whistler threatened legal action unless Harper’s removed all references to Sibley. The dispute drew attention from the British and American press and helped make Trilby a sensation—with Whistler’s name permanently attached to the story. When the installments were published as a book, Sibley was removed completely.

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Studies for “Punch,” 1893–1895

album of drawings and autograph manuscripts

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This album of George Du Maurier’s sketches contains a portion of the manuscript of Trilby concerning Joe Sibley—an unflattering character based on Whistler. It also contains a draft of a letter from Du Maurier to Whistler in which he offers regrets for any offense given. Du Maurier writes that, “None of my characters were intended for real portraits. You were quite mistaken about my motives. I hope it is no libel to say that I have never been [jealous?] of you; nor (as you seem to think) afraid—nor have I ever borne you any ill will.” The publisher, Harper’s, printed a public apology to Whistler, but it is not clear if a version of this more personal missive was ever sent.

![James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888. Author’s presentation copy to Beatrix Whistler, accompanied by a printed invitation to the lecture. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888. Author’s presentation copy to Beatrix Whistler, accompanied by a printed invitation to the lecture. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/53_Whistler_James_Ten_oclock_cover_invitation_better-scaled.jpg)