Of all the conflicts in Whistler’s career, his lawsuit against renowned art historian and critic John Ruskin was most significant. Ruskin wrote a particularly harsh review of Whistler’s paintings in an 1877 exhibition at London’s Grosvenor Gallery. He was incensed by the painting Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, which was radical in its nearly-abstract appearance. Ruskin criticized Whistler’s “ill-educated conceit,” famously writing, “I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

In response, Whistler sued Ruskin for libel. The trial in 1878 provided Whistler with the opportunity to present his artistic ideals before a wide audience. Significantly, Whistler defined his paintings as “an arrangement of line, form, and color first” and explained that in his art, he “wished to indicate an artistic interest alone.”

Although Whistler won the trial, the jury awarded him a mere farthing—a quarter of a penny—in damages. Forced to declare bankruptcy, Whistler accepted a commission to travel to Venice, where he would produce some of his most famous etchings.

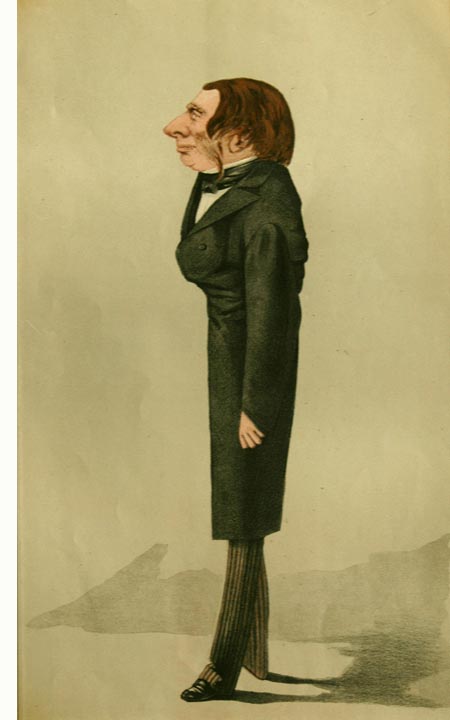

Adriano Cecioni (Italian, 1836–1886)

Men of the Day No. 40: “The Realisation of the Ideal,” 1872

color lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

John Ruskin was a prominent social theorist and the foremost art historian and critic of Victorian Britain. He attacked Whistler from a position of considerable authority, having been appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University, a position that he held from 1869 until 1878. Captioned “The Realisation of the Ideal,” this caricature from Vanity Fair simultaneously mocks Ruskin’s less-than-ideal rigid and awkward appearance and references his philosophies regarding society and art. Ruskin believed that art had a moral purpose and should be used to uplift society, a philosophy that was in conflict with Whistler’s view that art was, foremost, an arrangement of visual elements.

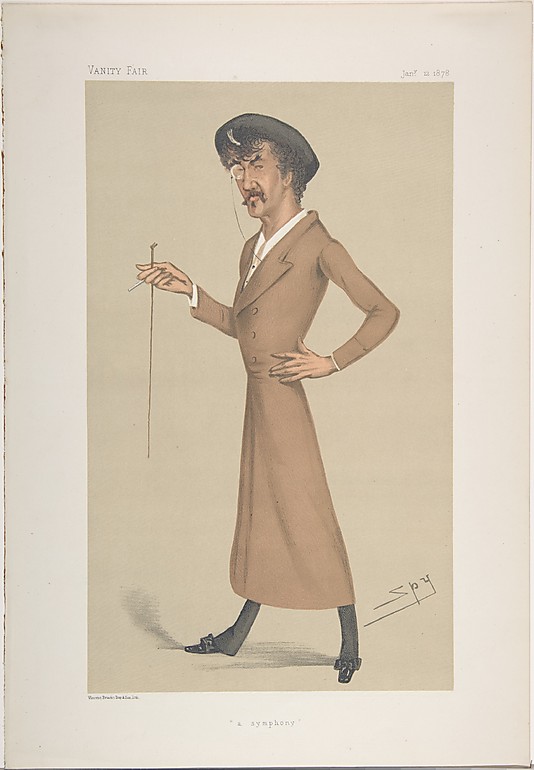

Leslie Matthew Ward (known as Spy), (British, 1851–1922)

A Symphony, 1878

color lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This caricature of Whistler was published in Vanity Fair in January of 1878, a month after John Ruskin’s counsel filed the first official response to Whistler’s libel lawsuit. It contains many of the characteristic elements in portraits of Whistler, including his monocle, walking stick, cigarette, and the prominent lock of white hair that protrudes from his hat. The caricature was accompanied by a brief biography that addressed Whistler’s artistic theories. In it, the anonymous author defended Whistler’s art in language that would be repeated during the trial. “He has been accused of not finishing his pictures,” the author wrote, “but ‘finish’ is a word that has been abused to convey the more apparent absence of a conventional amount of labour which he rejects…and replaces by his assurance that he has done the work when he has done with it.”

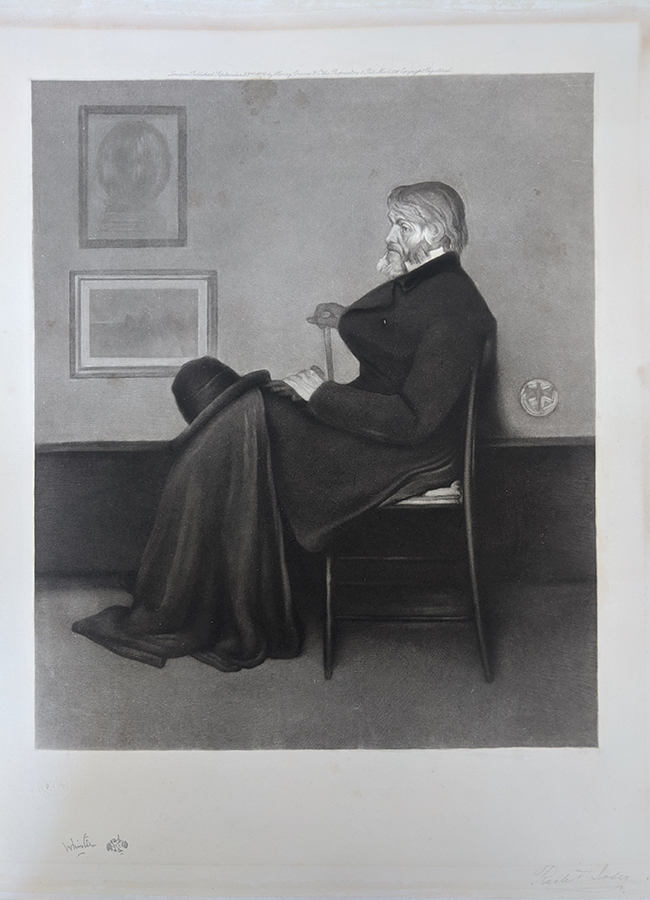

Richard Josey (British, 1840 or 1841–1906), after James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2, Thomas Carlyle, 1878

mezzotint on paper, London: Graves

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Oscar Wilde called the portrait of the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle the “one really good picture” among the paintings that Whistler exhibited at the controversial Grosvenor Gallery exhibition in 1877, which led to the legal dispute with John Ruskin. In pose and mood, the composition reflects Whistler’s well-known portrait of his mother.

This mezzotint reproduction was made “under the immediate supervision of the painter.” It was produced in September 1878, shortly before the Whistler v. Ruskin trial began.

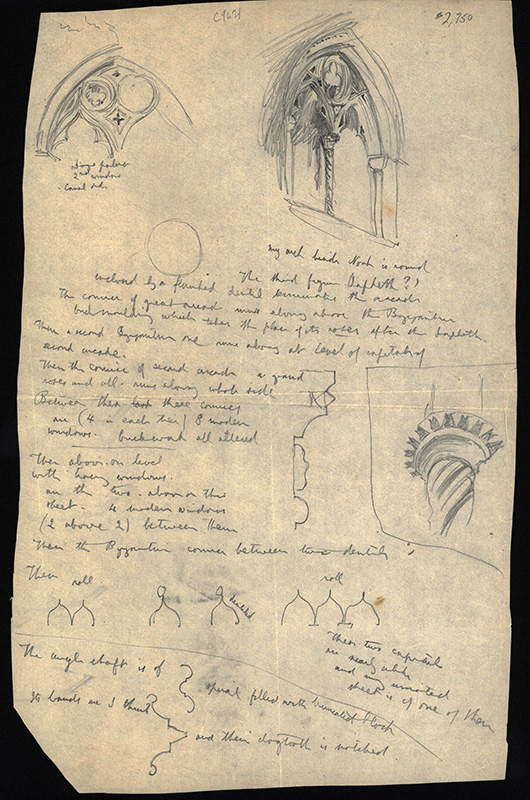

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900)

Notes for The Stones of Venice, c. 1850

autograph manuscript with sketches

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This sheet contains notes and sketches that John Ruskin used when preparing his multivolume architectural treatise, The Stones of Venice. In it, Ruskin questions the relationship between art and society, arguing that the decline in Venice’s morality—manifested in its art and architecture—presents a warning for England. Ruskin’s opposition to Whistler’s art was an extension of these views. He believed in the moral value of art and railed against what he saw as amorality and consumerism in Whistler’s work.

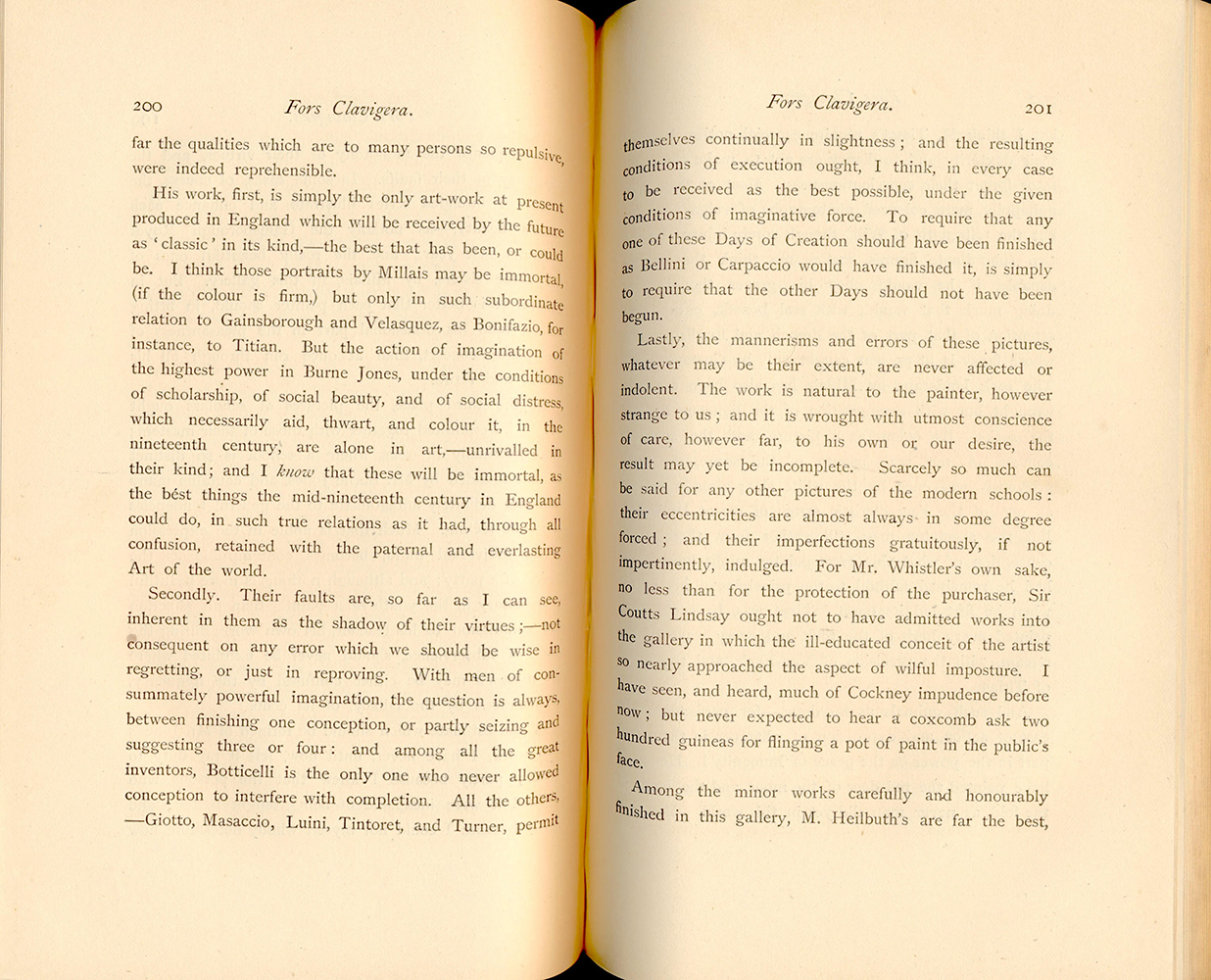

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900)

Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain. London: Printed for the author by Smith, Elder & Co. ... and sold only by Mr. G. Allen ..., 1871–1884

Special Collections

John Ruskin launched his attack on Whistler in July 1877 in letter 79 of Fors Clavigera, his series of polemical pamphlets. Appended to a lengthy discussion of the value of labor and money, Ruskin’s discussion of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition began with favorable comments on artworks by Edward Burne-Jones in the exhibition. Turning his attention to Whistler, whom he negatively contrasted with Burne-Jones, Ruskin wrote:

“For Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted work into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Several London newspapers reported Ruskin’s statement, bringing it to Whistler’s attention.

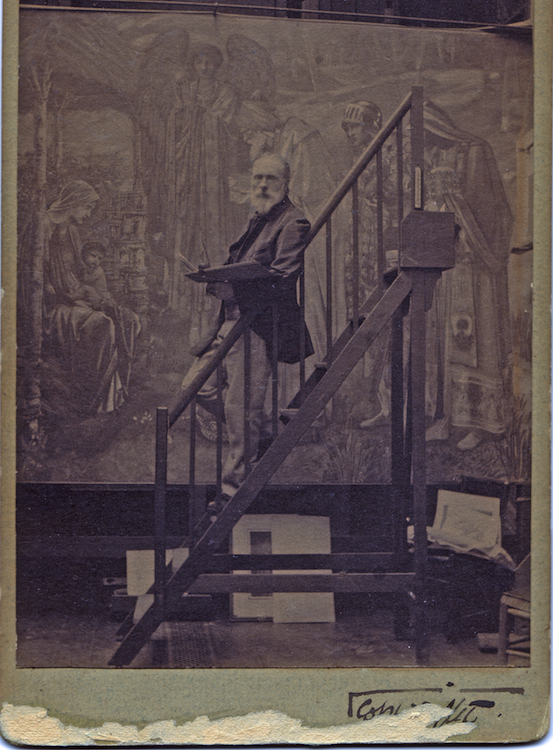

Barbara Leighton (British, 1870–1952)

Edward Burne-Jones, c. 1890

platinum print cabinet card

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Edward Burne-Jones was the star witness on Ruskin’s behalf in the Whistler v. Ruskin trial. This photograph shows him at work on the large watercolor painting The Star of Bethlehem. Relatively little is known about the photographer, Barbara Leighton. The daughter of a Conservative politician, she was especially known for her portraits of other artists.

Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898)

Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

NEW ACQUISITION

In early November 1878 John Ruskin asked Edward Burne-Jones to testify on his behalf at the upcoming Whistler v. Ruskin trial. Burne-Jones answered him in this letter, emotionally proclaiming his support for Ruskin in a stream-of-consciousness style of communication. Part of the letter reads, “if that advertising Yankee quack teases you I’ll kill him. I thought perhaps it was over. I’ll help in any way that I am told – turn up at a court like Mr. Winkle if you like – so will [William] Morris – it won’t bother you will it? I want peace for you and rest and friends all about spoiling you....,” adding in a postscript, “I have re-read the bit about your commission to lawyers. But I am to be teased & want it. It’s no teasing – I’ll do anything more than gladly.” Despite Burne-Jones’s uneven testimony at the trial, his correspondence indicates the depth of his support for Ruskin.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]

Inscribed by Rosa Corder to Frank Newburn

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Less than a month after the trial ended, Whistler published the first of his infamous brown-paper pamphlets. The seventeen-page volume Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics presents the artist’s view of the trial and its significance. Casting the legal battle in moral terms, the text argues against the role of critics in the art world—a claim that Whistler would continue to make throughout his career. The pamphlet was an immediate success. In the two months after the trial, five editions of the volume appeared, bringing widespread attention to Whistler’s account of what he called “a battle fought for the painters.”

Rosa Corder, an artist and one of Whistler’s models, owned this copy of the pamphlet.

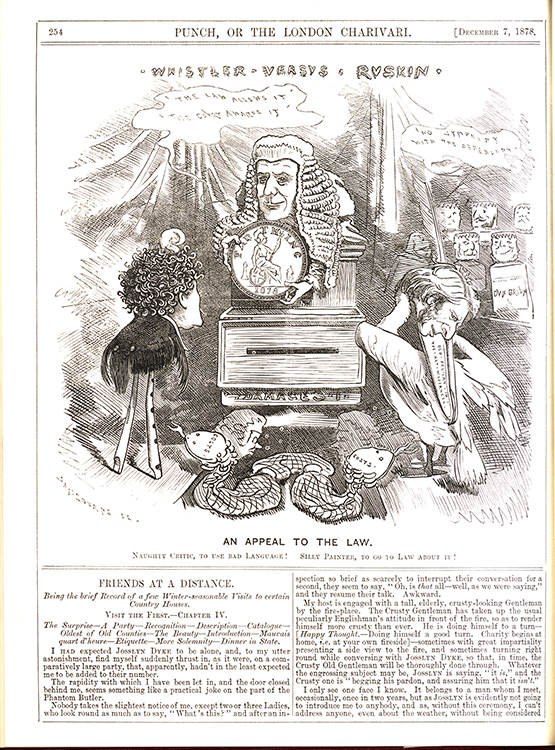

Edward Linley Sambourne (British, 1845–1910)

“An Appeal to Law,” in Punch, 7 December 1878

University of Delaware Library

Showcasing the widespread interest in Whistler and his lawsuit against John Ruskin, this illustration from the popular periodical Punch lampoons both men. The judge, wearing a legal barrister’s wig, presents an oversized farthing to Whistler, highlighting the meager award he received for victory in the legal dispute. Ruskin, identified as the “old pelican in the art wilderness,” looks downward in a way that suggests decapitation. The two-headed snake at the bottom of the illustration indicates the ultimate result of the trial. Labeled “costs,” it extends its tongue in the direction of both Whistler and Ruskin, referencing the legal fees that each side was obligated to pay. Despite his success in the trial, Whistler’s obligation to pay his legal costs led to his financial ruin.

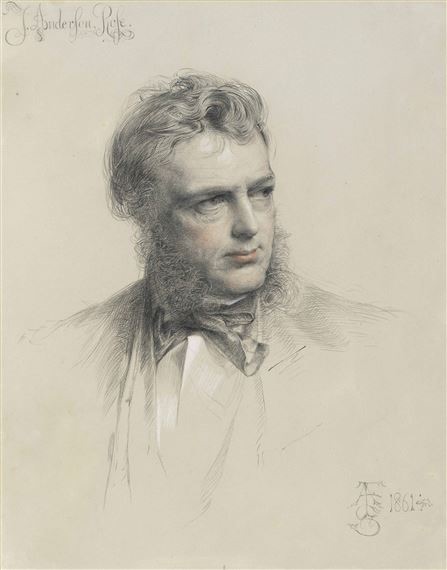

Frederick Sandys (British, 1829–1904)

James Anderson Rose, 1861

black, white, and red chalks on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

As Whistler’s solicitor, James Rose directed the legal strategy used in the Ruskin trial. He retained the barrister John Humffreys Parry to argue the case before the court.

Rose was a close friend and associate of many artists, including Whistler. He assembled a collection of artworks by his friends and clients, which included several paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and a prized collection of Whistler’s prints. This portrait drawing by the Pre-Raphaelite artist (and Whistler associate) Frederick Sandys appears to depict the sitter deep in thought, emphasizing his keen and penetrating mind.

Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898)

Virgil and the Muse of Poetry, c. 1880–1890

watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Edward Burne-Jones was a close friend of John Ruskin and one of the three witnesses who appeared on his behalf at the trial. Of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold—the painting that Ruskin specifically criticized in his review—Burne-Jones testified, “It would be impossible to call it a serious work of art.” One of Burne-Jones’s main complaints about Whistler’s art was its apparent incompleteness. Although he praised Whistler’s use of color, Burne-Jones criticized what he saw as a lack of form and “finish.”

As this watercolor indicates, Burne-Jones frequently depicted medieval and mythological subjects. This is one of a number of artworks that relate to Virgil or his epic poem, The Aeneid. The frame is original and was designed by the artist.

Albert Joseph Moore (British, 1841–1893)

Study of a Draped figure for the right-hand figure in The Shulamite, 1864

black and white chalks on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

Whistler and Albert Moore first met in 1865, the year after this drawing was made, and the two men developed a lifelong friendship. As one of Whistler’s three witnesses at the Whistler v. Ruskin trial, Moore was the strongest proponent of Whistler’s art during the proceedings. Despite differences in their preferred subject matter, Whistler and Moore shared an aesthetic affinity that celebrated “art for art’s sake.”

Like Whistler, Moore employed meticulous working methods. For each painting, Moore prepared numerous studies of figures and drapery. This characteristic study depicts an early pose, which Moore later modified, for one of the figures in his large 1866 painting, The Shulamite.

![Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898). Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898). Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2021/03/Burne-Jones-letter-to-Ruskin-combo.jpg)

![James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]. Inscribed by Rosa Corder to Frank Newburn. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]. Inscribed by Rosa Corder to Frank Newburn. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/37_Whistler_James_Whistler_v_Ruskin_cover1.jpg)