Whistler’s impact and eminent place within the art world extended beyond his own artistic production to encompass his aesthetic theories—which he regularly articulated in the press and in his own books—and his relationships with other artists and writers. In 1890, Whistler published his most famous book, The Gentle Art of Making Enemies, which contained selections from his earlier publications and his verbal jousts with his critics. While the book presented Whistler’s ideals, it also embodied them as a unified aesthetic production. After attracting numerous followers throughout his career, in the late 1890s Whistler attempted to formalize his role as an artistic master by establishing an art school, the Académie Carmen, in Paris.

Whistler’s renown grew both during his lifetime and after his death. This ongoing devotion among his many followers is sometimes wryly called the “Cult of Whistler.” Over time, the artistic and literary productions of his many followers and associates have assured Whistler’s legacy.

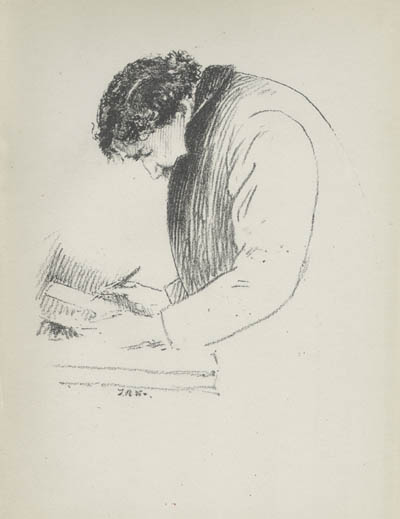

Thomas Robert Way (British, 1861–1913)

Sketch of Whistler When He was Retouching a Stone, 1895

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Thomas R. Way was the son of Whistler’s printer, Thomas Way. Over the course of their long relationship with Whistler, the Ways printed and helped to prepare Whistler’s prints, produced catalogues of Whistler’s major exhibitions, and authored texts on lithography and Whistler’s art. Significantly, the Ways introduced Whistler to various lithographic techniques and collaborated with him on lithographic projects.

Despite his contentious public persona, Whistler was meticulous about his art. Here Way shows him standing, deep in concentration, as he makes changes on a lithographic stone.

Less than a year after this portrait was made, a number of conflicts, including Whistler’s desire to control his publicity and disputes about the ownership of artworks in Way’s possession, led to the end of the relationship between Whistler and the Ways.

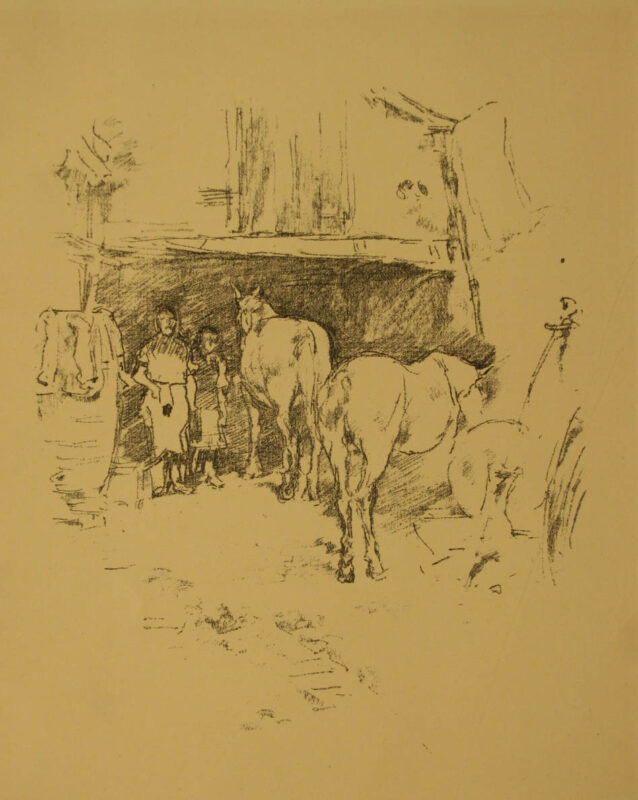

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Smith’s Yard, 1895

lithograph on paper

Museums Collections

Whistler produced lithographs throughout his career, but he devoted particular attention to the medium in the 1890s. He was especially important in advocating for the elevation of lithography from its association with commercial use to the realm of fine art.

Whistler spent the autumn of 1895 in Lyme Regis, a resort town on the English coast. The blacksmith’s yard in this print was not far from Whistler’s studio, and Whistler made numerous depictions of the smith, his property, and members of his family. Scenes of everyday life and labor are seen from the beginning of Whistler’s career to his last decade of work.

Walter Richard Sickert (British, 1860–1942)

St. Jacques, Dieppe from the Rue Pecquet, c. 1900

ink, charcoal, and wash on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In 1885, Whistler joined his pupil and assistant Walter Sickert at the French resort town of Dieppe. The experience marked the beginning of Sickert’s decades-long fascination with Dieppe. The Gothic church of St. Jacques particularly appealed to Sickert, who depicted it over two dozen times. The loose, shadowy rendering of this drawing is reminiscent of Whistler’s cityscapes and Whistler’s interest in exploring the aesthetic potential of complex building facades.

Sickert’s interest in Dieppe would outlast his relationship with his former artistic mentor. After a series of disputes, the two artists became estranged in 1896.

Augustus John (Welsh, 1878–1961)

Ida Nettleship, 1899–1900

pencil on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

As a young artist, Ida Nettleship studied at Whistler’s Académie Carmen in Paris. Here she is depicted in a pencil portrait by the Welsh painter Augustus John, whom she would marry in 1901. The composition is reminiscent of Whistler’s Symphony in White No. 2: The Little White Girl. (A photograph of that painting, signed by Whistler, is on view in the exhibition.) Yet while the subject of Whistler’s painting gazes dreamily into a mirror, Nettleship turns to look over her shoulder, directing her lively expression outward.

Gwen John (Welsh, 1876–1939)

Seated Cat, 1907

watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Gwen John is one of the best-known artists who studied at the Académie Carmen, the art school that Whistler founded in Paris. Her brother Augustus John described Whistler’s influence on his sister: “With some talented student friends she passed some time in Paris under the tutelage of Whistler. It was thus she arrived at that careful methodicity, selective taste and subtlety of tone which she never abandoned.”

Among John’s favorite subjects were her cats, which she frequently depicted in watercolors.

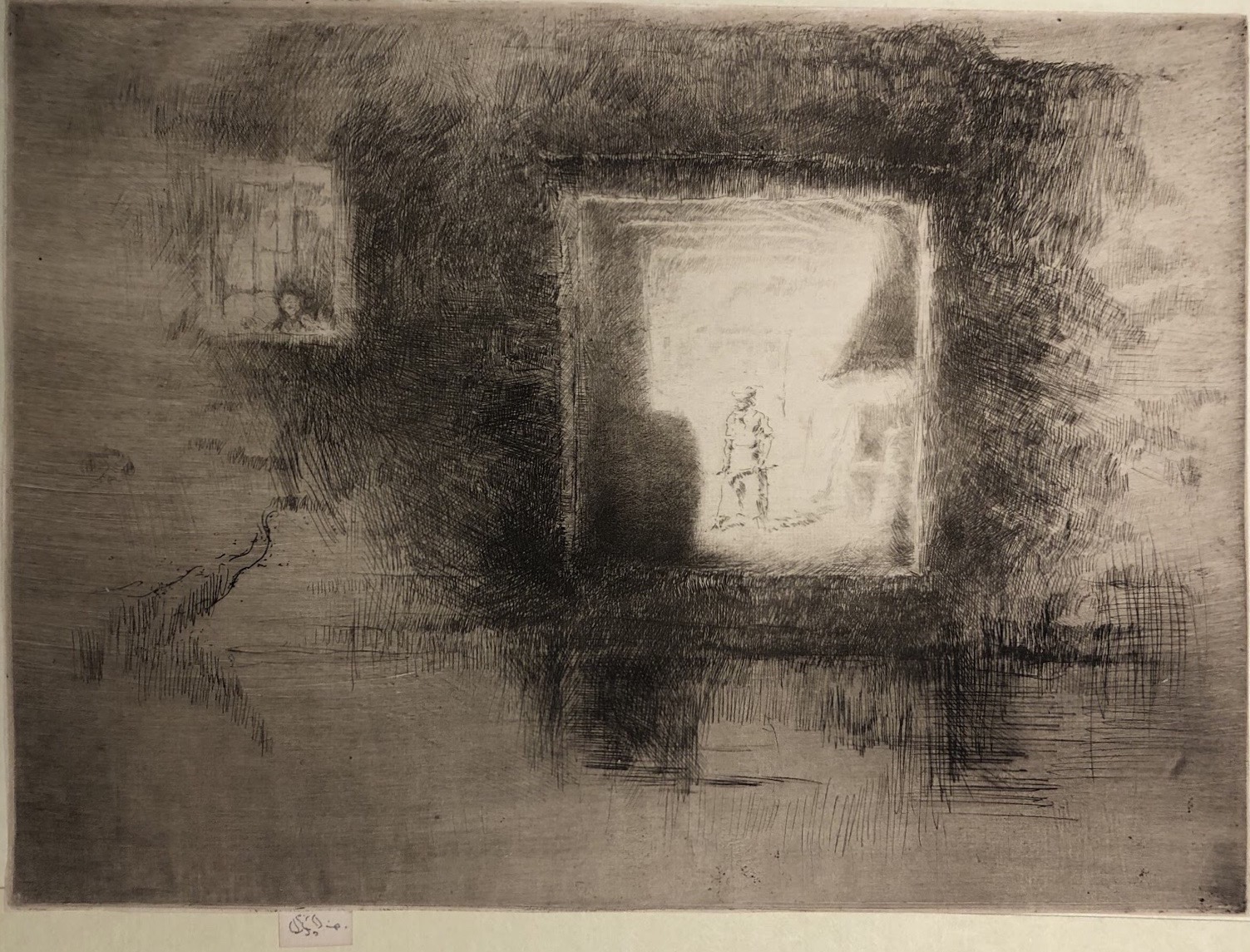

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Nocturne, Furnace, 1879–1880

etching on paper

Special Collections, A. J. Rosenfeld Etchings Collection

Whistler frequently incorporated views through doorways or other openings into his prints. This etching, made during the artist’s 1879–1880 sojourn in Venice, shows the canal door of a small workshop. The bright light from the furnace illuminates the worker who stands, wearing an apron, in the middle of the doorway. Dark, hatched lines around the doorway reinforce the nocturnal setting. The distinctive prow of a gondola floats in the water at left. Like many of Whistler’s etchings, this composition combines elements of detail at the center with a dissolving, ambiguous atmosphere at the edges.

This print was published in Whistler’s “Second Venice Set” in 1886.

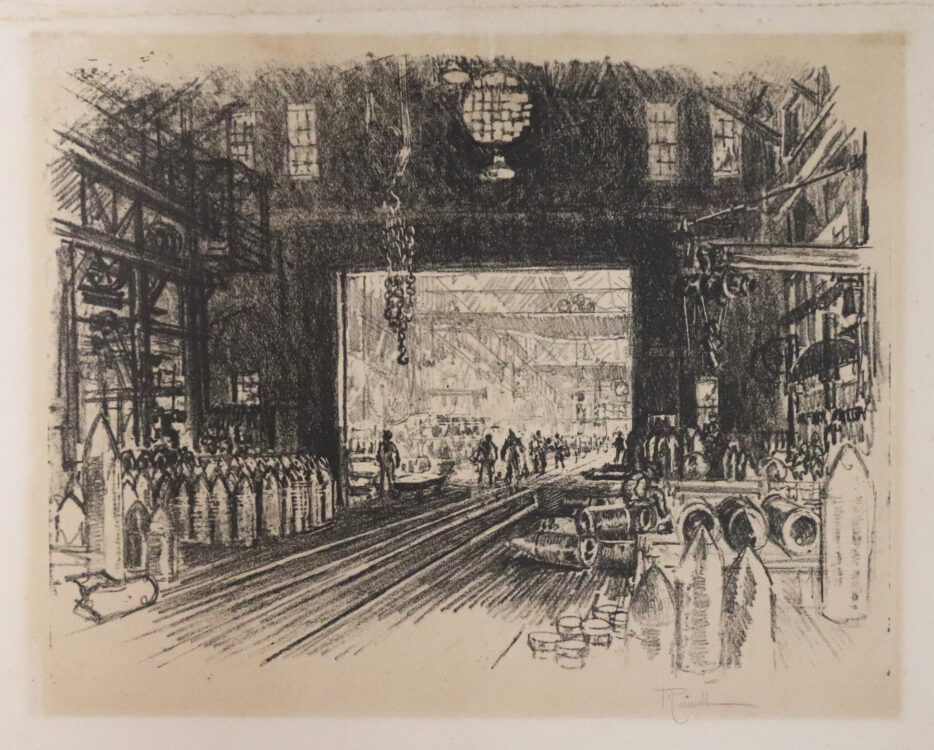

Joseph Pennell (American, 1857–1926)

Shell Factory, No. 2: from Shop to Shop, 1917

lithograph on paper

Museums Collections

Joseph Pennell was an artist, writer, and—along with his wife, Elizabeth—a friend and staunch supporter of Whistler and his art. This print shows the enduring impact of Whistler’s style and printmaking strategies on Pennell’s own work. Although it was made over a decade after Whistler’s death, the print, from Pennell’s series depicting the labor of war in Britain and the United States, utilizes the same compositional strategy seen in Whistler’s Nocturne, Furnace (nearby). Both Pennell and Whistler also shared an interest in labor as a subject.

Whistler and Max Beerbohm

Max Beerbohm was among the most significant caricaturists at the turn of the century. He met Whistler in London in 1896 and became engaged in a verbal exchange that was played out in the press. Mocking Whistler for his vanity, Beerbohm wrote, “[w]hile other great painters have…been tearing their hair, he has been arranging his before a mirror.” However, Beerbohm nonetheless appreciated the older artist’s writing, telling a friend that Whistler’s art criticism gave him “keenest delight.” He produced several caricatures of Whistler, both during and after the artist’s lifetime.

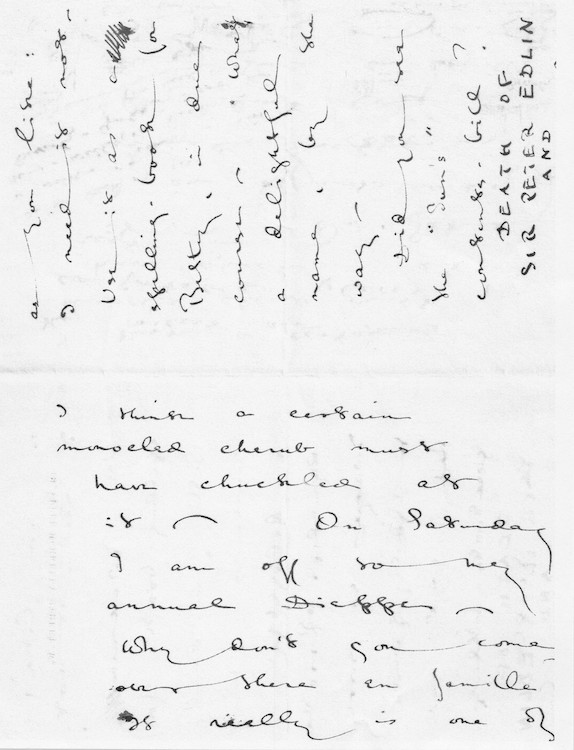

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Autograph letter signed to Eric Parker, c. 18 July 1903

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This letter references The Gentle Art of Making Enemies and asks if the recipient saw the headline in the Sun that linked the deaths of Whistler and Sir Peter Edlin, the judge who presided at the litigation William Eden brought against the artist. Of the connection, Beerbohm wrote, “I think a certain monocled cherub must have chuckled at it.” Whistler’s legal battles were clearly of interest to Beerbohm, who depicted the artist’s contentious legal proceedings in several caricatures.

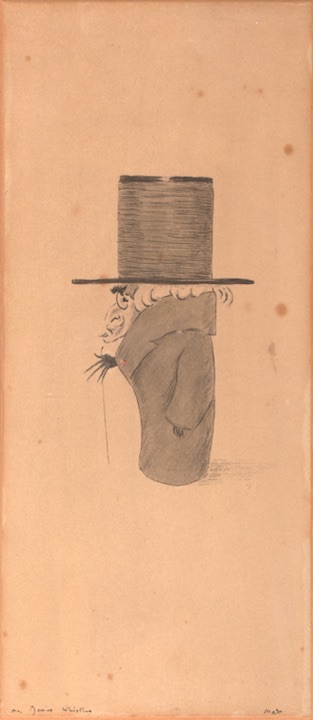

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Mr. James Whistler, c. 1900

ink and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This small caricature shows Whistler, buttoned up in an oversized coat, wearing a comically large hat. That Whistler appears swamped in his garments may be a reference to his slight figure. The artist wears a monocle and is depicted with a tiny red dot on his coat—likely a mocking reference to the medal that Whistler was frequently depicted wearing after being awarded the French Legion of Honor in 1889.

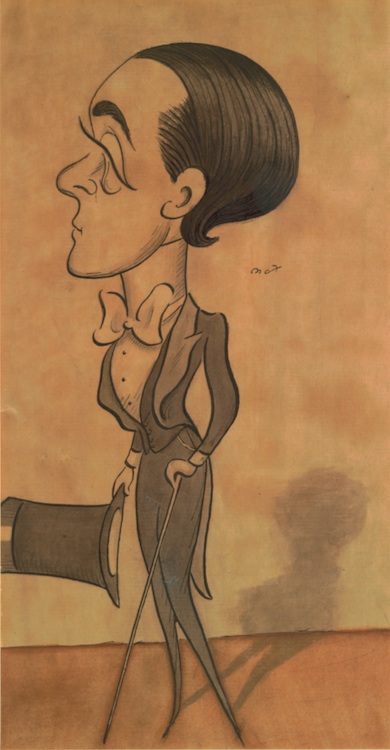

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Self-caricature, c. 1900

ink and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Made around the same time as his caricature of Whistler on view nearby, this self-portrait shows Max Beerbohm with similar accessories, including an exaggerated top hat, long coat, and walking stick. Beerbohm fashioned himself a dandy in the mold of Whistler or Oscar Wilde.

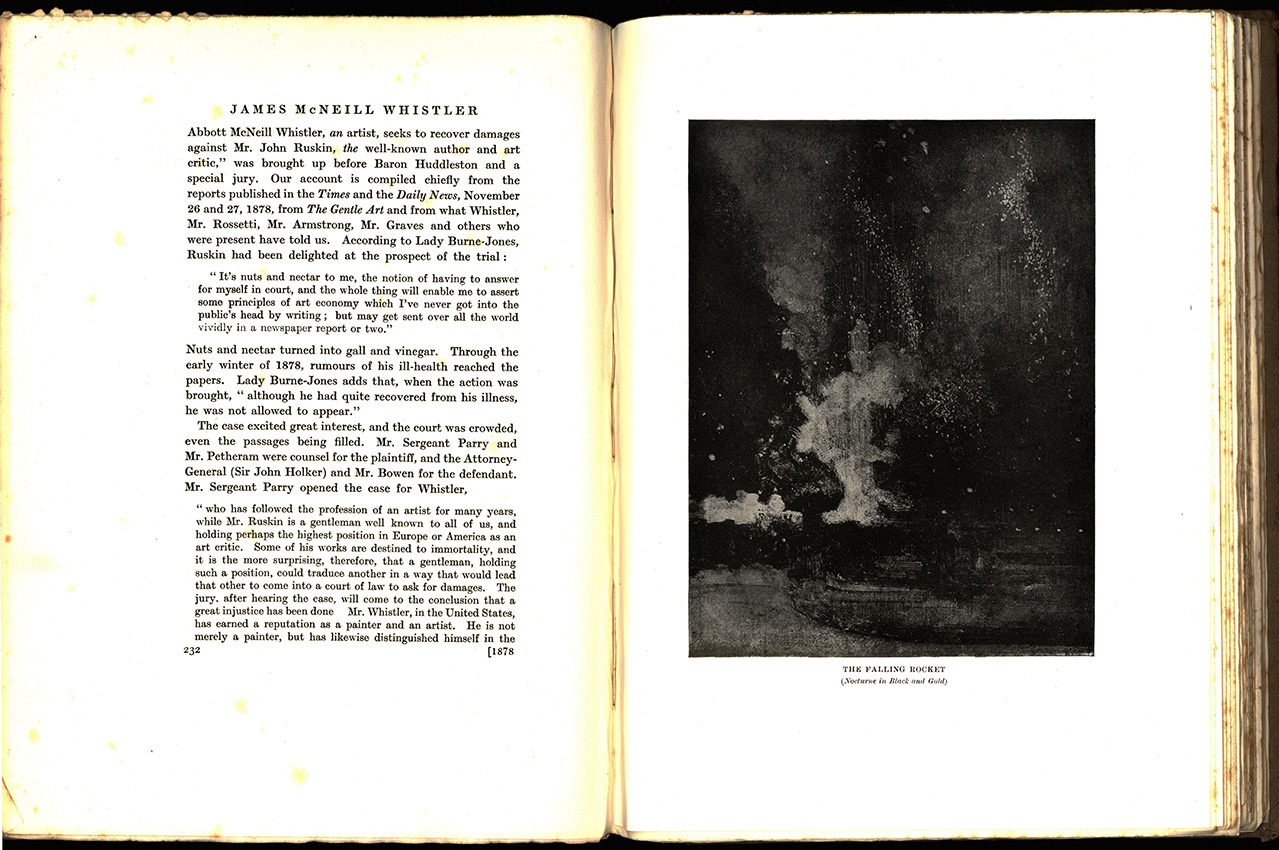

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. London: William Heinemann, 1890

Inscribed by Whistler to Ellen Sickert

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The publication history of Whistler’s notorious book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies is fraught with controversy and uproar—just like its contents. The project originated with an American journalist, Sheridan Ford, who proposed a book containing Whistler’s extensive published newspaper correspondence. After Whistler abruptly ended the project, Ford published the book anyway. Whistler sought legal intervention to stop the book’s distribution and determined to publish his own edition of The Gentle Art.

Whistler presented this inscribed first edition of the book to the artist Ellen (“Nellie”) Sickert, the wife of Whistler’s assistant and follower, Walter Sickert.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. A New Edition. London: William Heinemann, 1892

Inscribed by Whistler to George Moore

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Whistler approached the publication of The Gentle Art of Making Enemies with the same care that he devoted to his art. He used quality paper and placed his unique butterflies in precise locations on the pages to interact with the text. The pared-down elegance of the book’s typography and its off-centered title page would greatly influence turn-of-the-century bookmaking. Beyond merely highlighting Whistler’s verbal battles with his enemies, the book presents Whistler’s aesthetic philosophy as articulated in the Ruskin trial and the “Ten O’Clock” lecture.

Whistler presented this expanded later edition of the book to the Irish novelist, critic, and champion of the Impressionists, George Moore—a Whistler frenemy.

Cope's Mixture: Selected from his Tobacco Plant. Liverpool: At the Office of Cope's "Tobacco Plant," 1893. No. 8 of Cope's Smoke-Room Booklets

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This advertisement from a Liverpool tobacco company shows how successfully Whistler’s Gentle Art of Making Enemies became a part of British popular culture. Although Whistler’s name does not appear, the reference is unmistakable: at the top of the page, a caricature of the artist—complete with monocle and pipe—takes the form of a butterfly, complete with a stinger.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]

Inscribed by Whistler to his sister, Deborah Haden

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Eden versus Whistler, the last of Whistler’s publications, again highlights a public quarrel. It details Whistler’s legal battle with Sir William Eden. In 1894, Eden commissioned a portrait of his wife. Due to a dispute about money, Whistler refused to hand over the portrait (and eventually returned the commission). Eden sued. Following several appeals, the court ruled in Whistler’s favor. It decreed that in a contract between an artist and a patron, the artist must not be obligated to submit an artwork with which he is not satisfied.

The book provides a lopsided view by only conveying Whistler’s perspective. Strategically, Whistler had the volume printed in Edinburgh but published in Paris to avoid the possibility of a libel suit from Eden. Whistler presented this copy to his half-sister, with whom he remained on good terms despite his quarrels with her husband, Francis Seymour Haden.

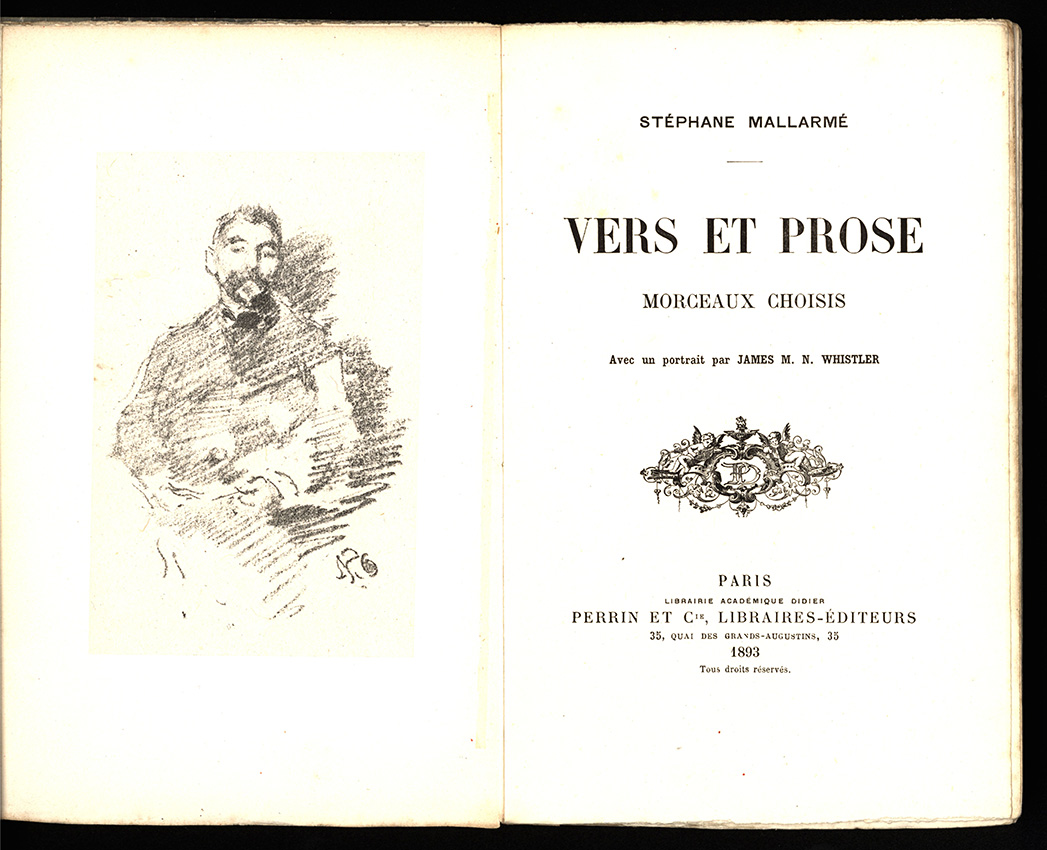

Stéphane Mallarmé (French, 1842–1898)

Vers et prose: morceaux choisis; avec un portrait par James M.N. Whistler. Paris: Perrin et cie., 1893

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Whistler and Stéphane Mallarmé, the French Symbolist poet, had a lasting fellowship based on shared aesthetic ideals, such as the importance of “art for art’s sake.” The two men became friends in 1888 after Claude Monet introduced them. Mallarmé agreed—or in some accounts, volunteered—to translate Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” lecture into French. He also spearheaded a plan for the French government to acquire Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, the portrait of Whistler’s mother, for the Luxembourg Museum.

Like Mallarmé’s poetry, the portrait is evocative and suggestive, as it depicts the seated poet emerging from dark shadows. In a letter to Whistler, Mallarmé wrote, “This portrait is a marvel, the best thing that has ever been done of me, and I am delighted with it.”

Stéphane Mallarmé (French, 1842–1898)

"The Whirlwind," in The Whirlwind, 15 November 1890

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In 1890, Whistler asked poet Stéphane Mallarmé to publish a poem in the English newspaper The Whirlwind. The periodical devoted particular attention to the arts, including printing several of Whistler’s lithographs as supplements in select issues. Referencing the newspaper’s title, Mallarmé’s poem takes the whirlwind as its inspiration. Later called “Billet à Whistler,” or “Note to Whistler,” the poem conveys the triumph of art in society. It ends with a rhyme incorporating Whistler’s name.

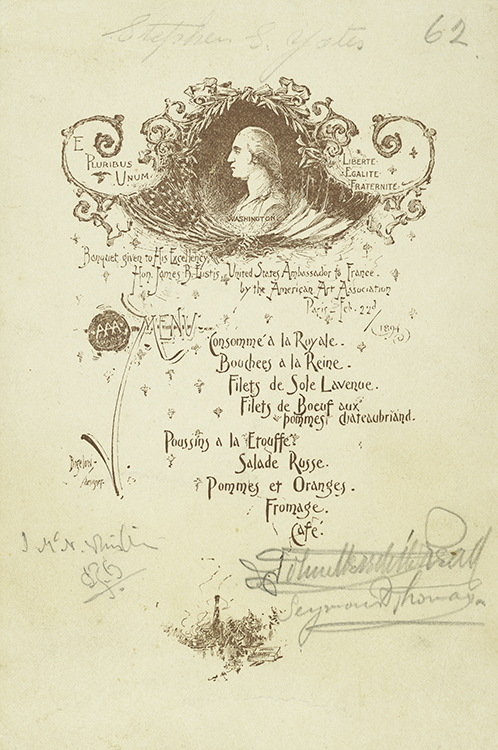

Menu for a dinner held by the American Art Association in Paris, 22 February 1894

Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera

Exhibited Spring 2021

Whistler increasingly fostered international connections in the 1890s. This souvenir menu records the attendees at a dinner held by the American Art Association of Paris, a social club for young American artists. Of the forty-two signatures, Whistler’s name and butterfly monogram is among the most prominent.

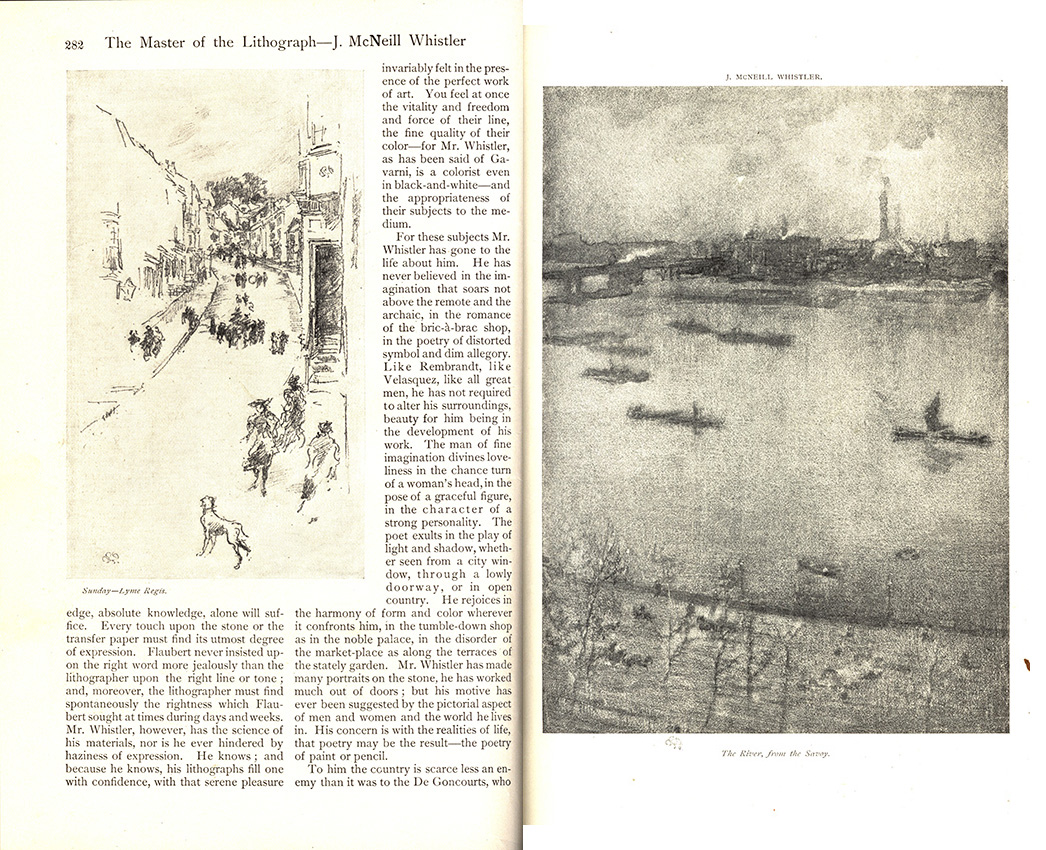

Elizabeth Robins Pennell (American, 1855–1936)

“The Master of the Lithograph—J. McNeill Whistler.” In Scribner’s Magazine, March 1897

University of Delaware Library

Elizabeth Pennell, along with her husband Joseph, played a key role in publicizing Whistler’s art for both British and American audiences. An art critic, travel writer, and expert on food, Pennell was a prolific journalist. In this article on Whistler’s lithography, Pennell argues that Whistler “revived an art which the world had conspired to forget.” The article reproduces a dozen of Whistler’s lithographs, including The Smith’s Yard (on view nearby).

Elizabeth Robins Pennell (American, 1855–1936) and Joseph Pennell (American, 1857–1926)

The Life of James McNeill Whistler. London: William Heinemann, 1908

Inscribed by William Heinemann to Sir George Lewis

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Joseph and Elizabeth Pennell both grew up in Philadelphia. They moved to London following their marriage in 1884 and met Whistler soon after. Tireless supporters of Whistler’s art and his legacy, the Pennells produced dozens of books and articles about Whistler, including the contested biography, The Life of James McNeill Whistler. Although Whistler provided biographical information for the Pennells, following the artist’s death the couple became involved in a legal battle with his sister-in-law Rosalind Birnie Philip, who disapproved of the manuscript.

William Heinemann, publisher of both this book and Whistler’s Gentle Art of Making Enemies, presented this volume to Sir George Lewis. Lewis was Whistler’s longtime lawyer and a close friend.

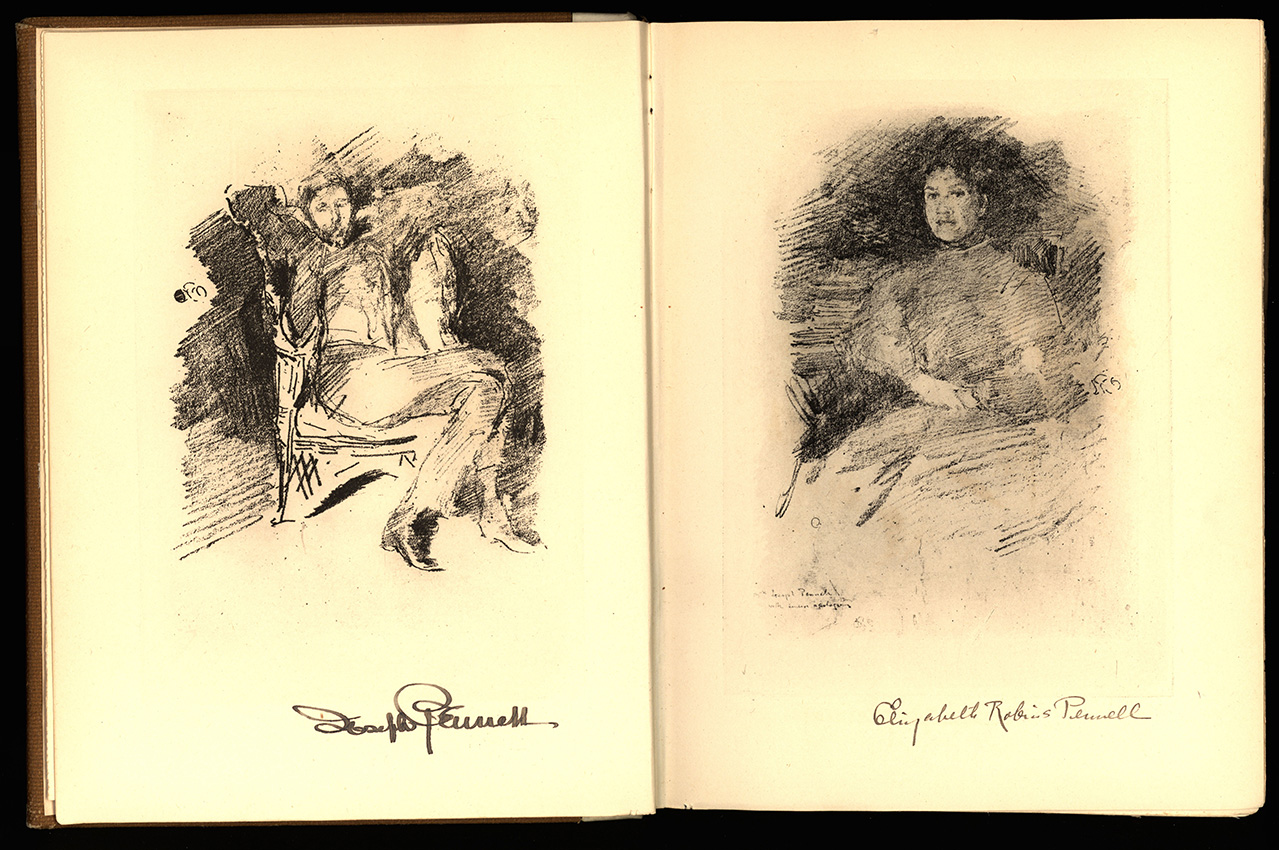

Elizabeth Robins Pennell (American, 1855–1936) and Joseph Pennell (American, 1857–1926)

The Whistler Journal. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott, 1921

Special issue

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In 1896, Whistler made lithographic portraits of some of his most devoted followers, Joseph and Elizabeth Robins Pennell, seated in front of the fireplace in their London flat. The Pennells included reproductions of the portraits in The Whistler Journal, a compilation of records and conversations with Whistler’s friends and associates that the Pennells gathered to prepare their 1908 biography, The Life of James McNeill Whistler.

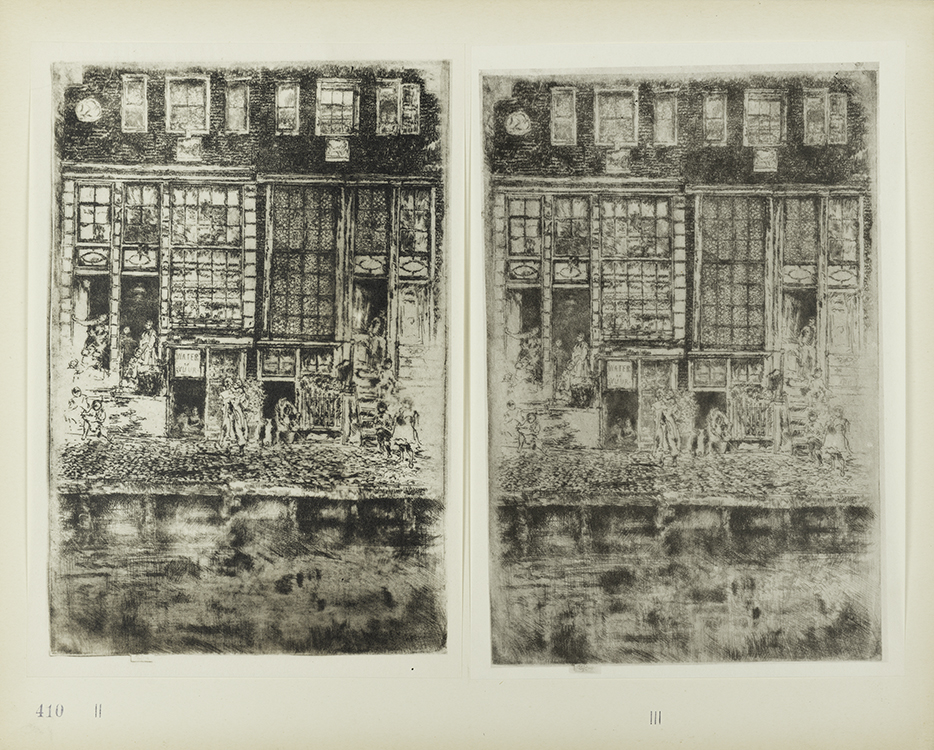

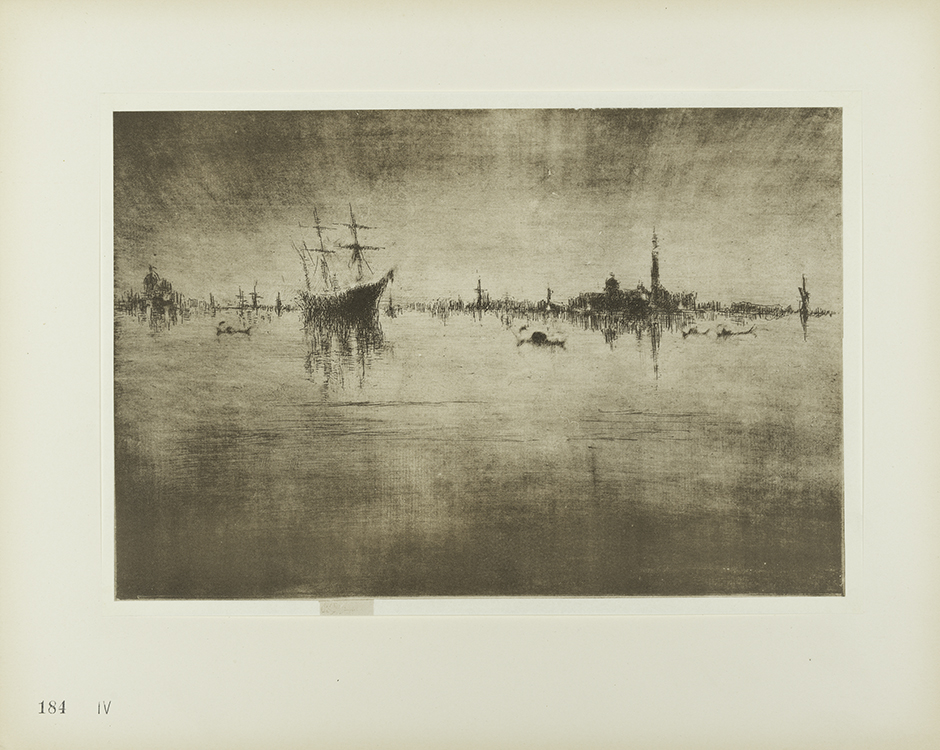

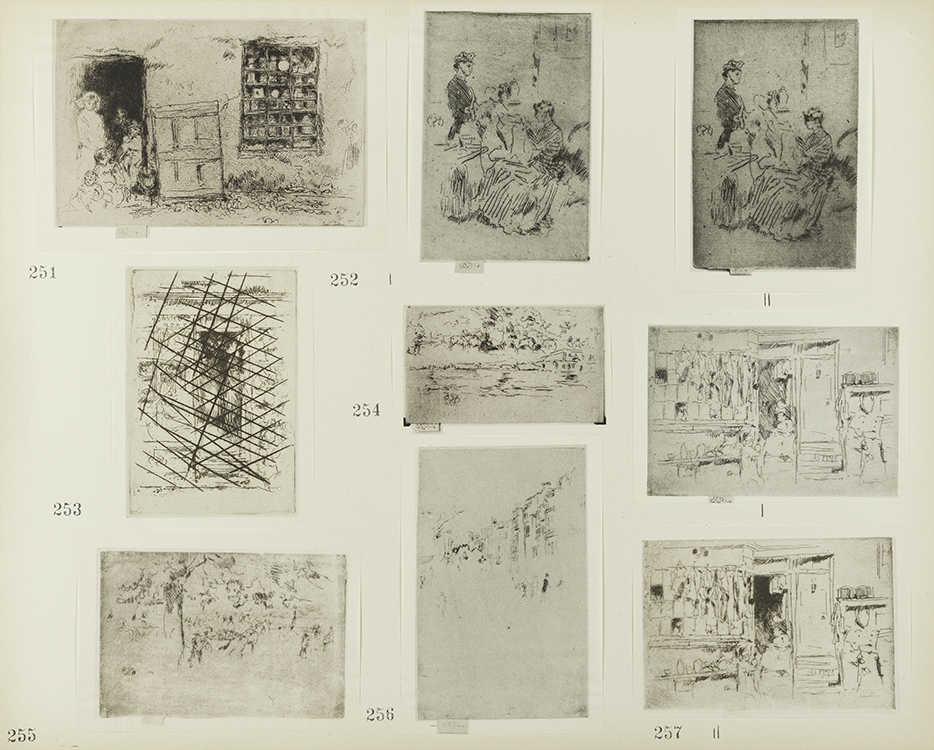

Edward G. Kennedy (American, 1849–1932)

The Etched Work of Whistler: Illustrated by Reproductions in Collotype of the Different States of the Plates; Compiled, Arranged and Described by Edward G. Kennedy; With an Introduction by Royal Cortissoz. New York: Grolier Club, 1910

Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection

Following Whistler's death in 1903, interest in his life and work grew into a virtual cult. Prices of the artist’s work increased as major collections were formed, exhibitions abounded, memoirs by Whistler’s friends appeared, critical appraisals were published in a dozen languages, and products as different as cigarettes and playing cards were embellished with his image. The Arrangement in Black and Grey, commonly called “Whistler’s Mother,” became one of the most reproduced artworks of all time.

Perhaps the most grandiose accolade was this extraordinary catalogue, published in 1910 at the then-enormous price of $100 by the Grolier Club, a New York society for book and art collectors. Its 200-page volume of text and three massive portfolios, containing over 1,000 glued-in photographs, reproduces the different states of Whistler’s etching oeuvre at a level of detail not given to any previous artist. The volumes were compiled by Edward Kennedy, a friend of Whistler and the artist’s principal dealer in the United States.

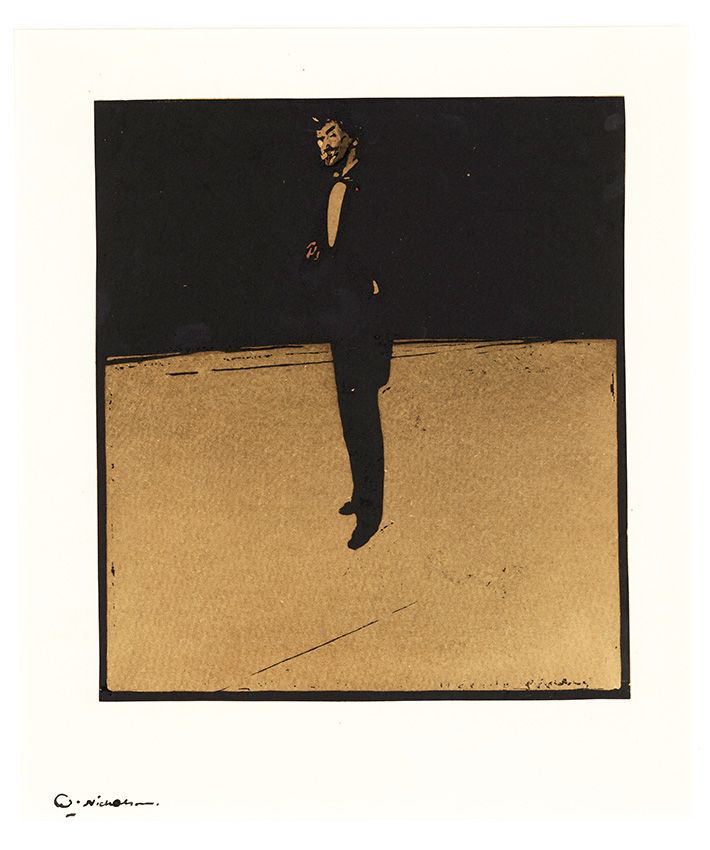

William Nicholson (British, 1872–1949)

James McNeill Whistler, 1897

hand-colored woodcut on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Whistler was acutely aware of the artist’s role as a public figure. He carefully crafted the public persona that William Nicholson portrays in this dramatic woodcut. Depicted in evening attire in a vast empty space that suggests a stage, Whistler epitomizes the figure of the elegant dandy. His celebrity is affirmed by the circumstances of the print: it is part of a series of depictions of recognizable public figures that included Queen Victoria and Rudyard Kipling.

Nicholson’s affinity for Whistler began early. As a student, he left art school after producing an artwork that his teacher described as “a piece of Whistlerian impudence.” Active as an illustrator throughout his career, Nicholson famously provided artwork for the children’s book The Velveteen Rabbit.

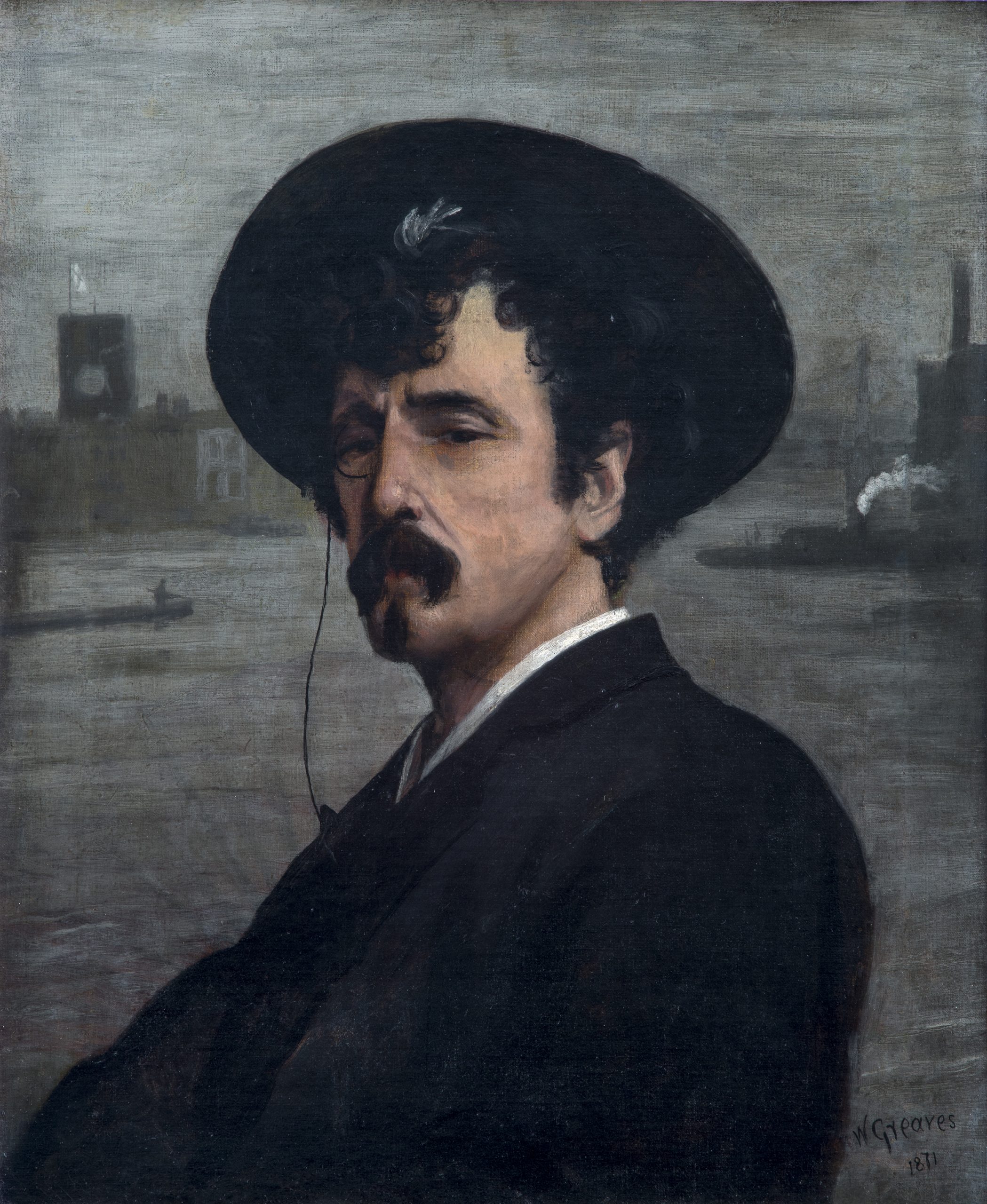

Walter Greaves (British, 1840–1930)

Whistler on the Thames, 1871

oil on canvas

La Salle University Museum, Gift of the Rosenbach Museum and Library

By situating Whistler “on the Thames” in this portrait, Walter Greaves—from a family of rivermen—evokes the many times he and his brother Henry rowed with Whistler on the river. The painting is a testament to Greaves’s understanding of Whistler’s character, his distinctive personal presentation (including his monocle and white forelock), and his aesthetics as an artist. Greaves’s atmospheric rendering of the river backdrop is strongly evocative of Whistler’s own nocturnal views of the Thames and may even reference a specific Whistler painting.

Greaves was a neighbor to Whistler in Chelsea, as well as an important early follower and an assistant. Notably, Greaves assisted with Whistler’s work on the Peacock Room. As with many relationships explored in this exhibition, Greaves and Whistler grew apart in the 1880s.

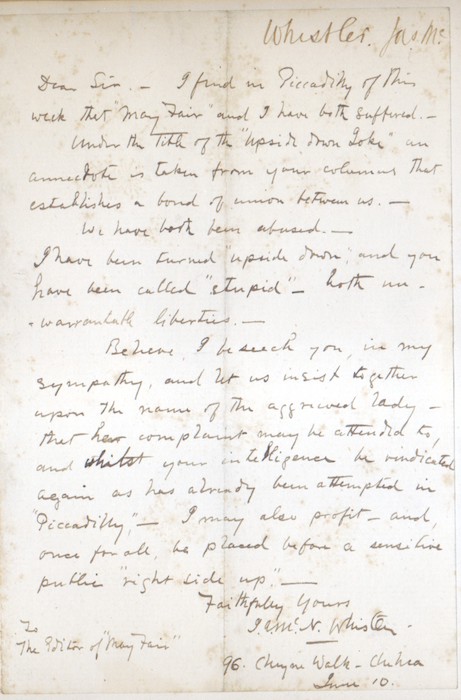

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834-1903)

Autograph letter signed to the editor of Mayfair, June 10, 1878

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

NEW ACQUISITION

Once he became a well-known figure, Whistler brought himself before the public through a seemingly constant stream of letters to the press. In May of 1878, the weekly newspaper Mayfair published an article recounting how “a lady of aesthetic tastes” loaned a Whistler painting to an exhibition and was shocked to discover that it had been hung upside down. Piccadilly magazine responded with “The Upside Down Joke,” in which “A Brother Artist” called Mayfair “that stupid print” and mocked it for employing a cliché.

Whistler joined in the fun with this letter to Mayfair’s editor. He writes: “We have been both abused – I have been turned ‘upside down,’ and you have been called ‘stupid’ – both unwarrantable liberties – Believe, I beseech you, in my sympathy, and let us insist together upon the name of the aggrieved lady – so that her complaint may be attended to – and whilst your intelligence be vindicated again as has already been attempted in ‘Piccadilly’ – I may also profit, – and, once for all, be placed before a sensitive public ‘right side up.’”

![James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]. Inscribed by Whistler to his sister, Deborah Haden. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection. James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]. Inscribed by Whistler to his sister, Deborah Haden. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/74_Whistler_James_Eden_vs_Whistler_title_page1.jpg)