There is nothing like a good fight!—Whistler, 1880

James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), the expatriate American artist, had a formidable presence. He was known for his consummate skill as a painter and printmaker, for his radical art theories, for his wit—and for his combative persona that repeatedly led his friendships to devolve into feuds. Whistler’s forceful personality was at odds with the delicacy of his art. His iconic signature of a graceful butterfly with a barbed stinger embodies this contradiction.

Inspiring many and reviled by some, Whistler courted controversy throughout his life.

Friends & Enemies: Whistler and his Artistic, Literary, and Social Circles explores Whistler’s high-profile place in the art world and in the literary and social worlds of Paris and London. Tracing famous controversies, such as Whistler’s lawsuit against art historian John Ruskin and his verbal sparring with Oscar Wilde, the exhibition has at its core an array of Whistler’s etchings and lithographs. Printmaking was central to Whistler’s career and he is considered one of the great masters of etching and lithography. Whistler’s prints and writings are juxtaposed here with works on paper, photographs, books, periodicals, and ephemera by his associates and the followers who helped ensure his long-lasting legacy.

This exhibition brings together materials from the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, Museums, and Special Collections, all part of University of Delaware Library, Museums and Press, and from important lenders.

The exhibition was curated by Ashley Rye-Kopec, Curator of Education and Outreach, Museums; Mark Samuels Lasner, Senior Research Fellow, Special Collections; and Amanda Zehnder, Chief Curator, Museums. All of the content in the forthcoming gallery installation is represented in this presentation online. Assistance in research, design, and installation of this exhibition was provided by Jan Broske, Danielle Canter, Tim English, Colleen Estes, Dustin Frohlich, Brian Kamen, and Kris Raser.

The Butterfly’s Family and Background

Whistler’s Arch, 2016

Brendan Devlin

Whistler’s Arch, 2016

platinum-palladium on on Bergger COT320 paper

Museums Collections

Recent Acquisition

This recent photograph reflects the long legacy of Whistler and his father, engineer George Whistler. Whistler’s Arch depicts a stone railroad bridge in the Berkshire Mountains. George Whistler designed it around 1840, when he was the chief engineer for the Western Railroad of Massachusetts. Two years later, he received a commission from Czar Nicholas I to build a railroad in Russia and relocated the family to St. Petersburg.

Brendan Devlin made this photograph using the platinum-palladium technique, popular with late nineteenth-century Pictorialist photographers. Pictorialism’s heyday coincided with Whistler’s artistic career. Many Pictorialists idolized Whistler. The visual softness of this contemporary photograph is a hallmark of both Pictorialism and Whistler’s art.

More about this item

Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, c. 1872

John Robert Parsons? (Irish, c. 1826–1909), after James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother, c. 1872

albumen print

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This photograph was taken shortly after Whistler finished his most famous painting, the portrait of his mother Anna Matilda McNeill. She posed for it in 1871 while living in London with her son. The severity of the grey and black palette and of Anna’s stark profile reflect the sitter’s personality and piety. The careful treatment of her face reveals Whistler’s well-known affection for his mother. Yet, by using the detached term “Arrangement” in the title, Whistler directed attention to the aesthetic elements of the painting and downplayed the subject matter. “Arrangement” also has a musical meaning. Whistler used musical titles repeatedly to draw a connection between the abstract quality of music and abstract aspects of composition in visual art. Notably, Whistler included his etching, Black Lion Wharf, 1859 (on view in this exhibition) in the background of this painting.

Whistler earned money with photographs of his paintings and shared them with colleagues. Here, Whistler’s inscription to his artistic follower Otto Bacher probably dates between 1879 and 1886.

More about this item

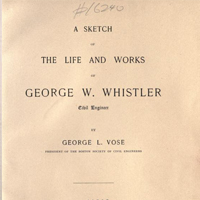

A Sketch of the Life and Works of George W. Whistler, Civil Engineer. Boston: Lee and Shepard; New York, C. T. Dillingham, 1887

George L. Vose (American, 1831–1910)

A Sketch of the Life and Works of George W. Whistler, Civil Engineer. Boston: Lee and Shepard; New York, C. T. Dillingham, 1887

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This book is a tribute to the career of Whistler’s father, George Washington Whistler, who died in 1849. It was written by another civil engineer, George L. Vose, a professor at Bowdoin College and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Both George Whistler and Vose specialized in the construction of railroads.

More about this item

Cope’s Christmas Card, 1883, 1883

John Wallace (known as George Pipeshanks), (British, 1841–1903)

Cope’s Christmas Card, 1883, 1883

watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

John Wallace’s bustling scene, much like this exhibition, illustrates Whistler’s place within the late nineteenth-century cultural world. Whistler is caricatured—sitting on a ladder at upper right in front of the School of Art—amidst sixty-seven celebrities of the day. Among them are Oscar Wilde—Whistler’s sometimes friend, sometimes rival—and John Ruskin, the art historian Whistler sued over a piece of negative criticism in one of his most notorious controversies.

The Liverpool firm Cope’s Tobacco, a pioneer in marketing and mail order sales, commissioned this watercolor to be distributed as a Christmas card for its customers. It was accompanied by a key identifying each figure.

More about this itemThe Butterfly in Paris

Street in Saverne, 1858

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Street in Saverne, 1858

From Douze eaux-fortes d’après nature (Twelve Etchings from Nature)—The “French Set”

etching on paper

Special Collections, A. J. Rosenfeld Etchings Collection

This moody etching was the first of many nocturnes in Whistler’s career. It shows a lone shadowy figure on a street in the Alsatian town of Saverne in northeast France.

It was part of his first published group of etchings called Douze eaux-fortes d’après nature (Twelve Etchings from Nature), commonly nicknamed the “French Set.” Whistler made the etchings, which include both landscapes and portraits, upon the urging of his brother-in-law Francis Seymour Haden and the set is dedicated to Haden. Haden encouraged Whistler to work directly from nature. The landscapes were produced from sketches Whistler made on paper, and some directly on copper plates, during a trip through France and the Rhineland in 1858. The first printing of the plates was done by master printer Auguste Delâtre in Paris. Shortly after, Haden made an edition in London.

More about this item

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903). La Vieille Aux Loques (The Old Rag Woman), 1858. From Douze eaux-fortes d'après nature (Twelve Etchings from Nature)—The “French Set”. Etching and drypoint on paper. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Richard G. Elliot, Jr., 1984.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

La Vieille Aux Loques (The Old Rag Woman), 1858

From Douze eaux-fortes d’après nature (Twelve Etchings from Nature)—The “French Set”

etching and drypoint on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Richard G. Elliot, Jr., 1984

In this image from the “French Set,” Whistler shows an elderly woman working on some rags by the light of the door with a kitchen behind her. This humble scene of labor reflects Whistler’s early interest in Realism. The compositional trope of a doorway that recedes into a detailed interior recurs throughout his career in different contexts. Often figures are framed by the doorways, as seen here, and in other instances the form of an empty doorway is the subject of aesthetic interest.

More about this item

Bibi Lalouette, 1859

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Bibi Lalouette, 1859

etching and drypoint on paper

Museums Collections

Recent Acquisition

Bibi Lalouette is one of many etched portraits of children Whistler made during his early years in Paris. This child was the son of a restaurant owner whose establishment was a frequent haunt of the Société des trois—Whistler and his friends Alphonse Legros and Henri Fantin-Latour. They accrued a sizable debt there, which Whistler eventually repaid. Even after Whistler left Paris for London in 1859, shortly after making this etching, he remained friendly with the Lalouette family.

Whistler’s visual strategy here, creating a detailed head and upper body, while the lower extremities and surrounding environment are left almost “unfinished,” is seen repeatedly in his etched and lithographic portraits. The question of a work being “finished” or not was controversial for many avant-garde artists in the nineteenth century. The charge of a work being “unfinished” was a criticism often leveled at Whistler.

More about this item

Professor Alphonse Legros, 1897

Sir William Rothenstein (British, 1872–1945)

Professor Alphonse Legros, 1897

from English Portraits, part VII

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This lithograph by William Rothenstein has several associations with Whistler. As a young artist in the 1890s, Rothenstein became a follower of Whistler in Paris. The portrait was printed by Whistler’s lithographer, Thomas Way. And the subject, Alphonse Legros, was one of Whistler’s earliest friends in Paris where Whistler, Legros and Henri Fantin-Latour formed the Société des trois.

Legros had an esteemed printmaking career. Originally from Dijon, France, Legros moved to London in 1863 upon Whistler’s urging and they lived together for a time. Subsequently, Whistler and Legros had a major falling-out. Legros later became Professor of Fine Art at the Slade School in London where Rothenstein was one of his students. Rothenstein became best known for portraiture, depictions of London synagogues, work as a war artist during the twentieth century, and for serving as Principal at the Royal College of Art.

More about this item

Extase poétique (Poetic Ecstasy), 1876

Alphonse Legros (French, 1837–1911)

Extase poétique (Poetic Ecstasy), 1876

drypoint on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Dr. George B. Tatum

This delicate drypoint was made by master printer, Alphonse Legros. A drypoint print is made by drawing directly into a copper printing plate with a needle, raising a burr of metal that traps ink and creates a velvety black appearance when printed. The strategy of concentrating detail in the face of the subject, while leaving the rest of the composition ambiguous is seen repeatedly in the work of Legros’s old friend Whistler. By the date of this print, 1876, the two had a complicated falling-out that ended their friendship.

1876 was a significant year for Legros professionally. He exhibited numerous prints at the second Impressionist exhibition in Paris, and became Professor of Fine Art at the Slade School in London.

More about this item

Algernon Swinburne’s photograph album

Algernon Swinburne’s photograph album

Contains 50 carte-de-visite photographs, most from the period 1863–1873

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

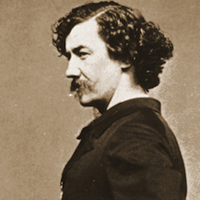

James McNeill Whistler, 1865

Etienne Carjat (French, 1828–1906)

James McNeill Whistler, 1865

albumen carte-de-visite

This well-known, dashing portrait by Parisian photographer, caricaturist, and journalist, Etienne Carjat, of a confident-looking Whistler was made during an important year for the artist. Whistler was becoming increasingly established as a notorious figure in the art world. In 1865 he exhibited works at both the Paris Salon and in London at the Royal Academy. In the autumn, Whistler and his model and lover, Jo Hiffernan, were in Trouville, France with Gustave Courbet, where the two artists painted seascapes. Shortly thereafter, Whistler had a falling-out with Courbet.

More about this item

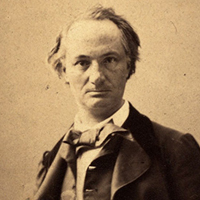

Charles Baudelaire, 1862

Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), (French, 1820–1910)

Charles Baudelaire, 1862

albumen carte-de-visite

This image of poet Charles Baudelaire was taken by one of the most famous photographers of nineteenth-century cultural celebrities, known by the pseudonym, Nadar. Among his many accomplishments, Baudelaire’s idea that art should depict everyday, modern life instead of traditional subjects involving mythology and religion, impacted a generation of avant-garde artistic practice—including Whistler’s choices of subject matter.

More about this item

Théophile Gautier, c. 1872

Charles Barenne (French, 1834–1913)

Théophile Gautier, c. 1872

albumen carte-de-visite

Théophile Gautier was a mid-nineteenth-century writer and an early advocate for the concept of “art for art’s sake.” This idea was one of the foundations of Aestheticism. It was a disavowal of narrative and any conceptual distractions from the primary importance of beauty, and abstract artistic concerns such as form and color.

More about this item

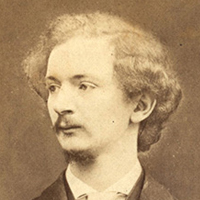

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1866

Elliott & Fry

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1866

albumen carte-de-visite

Algernon Swinburne, seen here, was the owner of this impressive compendium of photographs, largely depicting famous cultural figures of the late nineteenth century. Swinburne was a lyric poet whose poems were often deemed shocking for their frank content. He moved in Pre-Raphaelite circles and was friends with Whistler for many years. Swinburne and Whistler had a major falling out over Swinburne’s negative reaction to Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock,” a lecture published in 1888.

More about this item

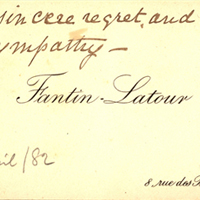

Calling card, 1882

Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836–1904)

Calling card, 1882

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Henri Fantin-Latour was one of Whistler’s most enduring friends and bridged Whistler’s Parisian and London worlds. He was the third member of the tight group called the Société des trois, which formed in Paris in the 1850s with Whistler and Alphonse Legros. Fantin-Latour also spent significant amounts of time in London with Whistler. This calling card demonstrates his (and Whistler’s) social connections with the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

Poignantly, this was sent on the occasion of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s death. It is inscribed, “With sincere regret and heart-felt sympathy” and endorsed “18 April /82” by William Michael Rossetti, who has written on the back, “The celebrated painter of flowers, etc. – Refers to Gabriel’s death.” Lush floral still lifes were among the most prevalent subjects in Fantin-Latour’s career.

More about this item

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1863 (printed 1882)

Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), (British, 1832–1898)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1863 (printed 1882)

albumen cabinet card

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In London Whistler became connected to many figures associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement, a group of painters, poets, and critics who, in 1848, formed a “Brotherhood” in protest against academic tendencies in contemporary British art. Whistler was attracted by their rebellious stance and became particularly friendly with the bohemian painter and poet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

This portrait was taken in October 1863 by author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, who was also a major photographer. Carroll visited Rossetti at his home in Chelsea, a neighborhood abutting the north side of the Thames, made fashionable by such artists as Rossetti and Whistler, who had moved there in 1863.

More about this item

Tannhaüser: Acte I: Venusberg, 1862–1876

Henri Fantin-Latour (French, 1836–1904)

Tannhaüser: Acte I: Venusberg, 1862–1876

lithograph on India paper

signed proof impression

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

Henri Fantin-Latour was one of Whistler’s most longstanding friends. The French artist’s work, however, departed strongly from Whistler’s art. In much of his printmaking, Fantin-Latour gravitated to sensual and narrative imagery, quite different from Whistler’s detached sensibility. Yet, they did share some interests. Both were early advocates for lithography as a purely artistic medium. This print was Fantin-Latour’s first attempt at making a transfer lithograph, a method in which the artist’s drawing on paper is transferred onto a printing stone. Many of Whistler’s own lithographs were made using this method.

Another of their common interests was the connection between visual art and music. While Whistler found a correlation between the abstract nature of music and compositional elements of paintings and prints, Fantin-Latour was more interested in illustrating musical narrative associations. This print’s subject is Richard Wagner’s opera Tannhaüser, here depicting the protagonist lounging with Venus in a decadent garden.

More about this item

Portrait of Sir Francis Seymour Haden, 1881

Alphonse Legros (French, 1837–1911)

Portrait of Sir Francis Seymour Haden, 1881

mezzotint on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

This mezzotint, a form of etching made using tools that create dots rather than lines, was made by Whistler’s old friend Alphonse Legros. It presents a stern portrait of Whistler’s brother-in-law, Francis Seymour Haden. By 1881, both Legros and Haden were out of favor with Whistler.

Legros, Haden, and Whistler were important figures in a phenomenon known as the etching revival in the late nineteenth-century art world, promoting etching as a fine art. In the early 1860s Legros was among the founding artists associated with the Société des Aquafortistes (Society of Etchers) in Paris, a group that helped modern artists produce and publish their etchings. Haden’s main career was as a doctor. Before he became an artistic etcher, he first learned etching techniques to hone his fine motor skills and to train his eye while studying to be a surgeon at the Sorbonne in Paris.

More about this itemThe Butterfly in London

Black Lion Wharf, 1859

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Black Lion Wharf, 1859

etching on paper

Special Collections, A. J. Rosenfeld Etchings Collection

When Whistler arrived in London in 1859, he chose to live in Wapping, a working-class district on the Thames. He wanted to understand life on the river. Wapping was filled with wharves, taverns, boarding houses, fishmongers, dock workers, and all manner of labor associated with the river.

The detailed line-work seen here was characteristic of Whistler’s early etching style. The worker in a barge in the immediate foreground is a compositional device that arrests the viewer’s eye before proceeding to the far shore and a ramshackle collection of buildings. The title of the print comes from a sign on a building at upper right, reading “Blac Lion Wharf” (with no “K”).

This print was published much later, in 1871 as part of the Series of Sixteen Etchings of Scenes on the Thames, commonly called the “Thames Set.”

More about this item

Battersea Reach, 1863

Sir Francis Seymour Haden (British, 1818–1910)

Battersea Reach, 1863

etching on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

Francis Seymour Haden made this sweeping view of the Thames from his brother-in-law Whistler’s window at 7 Lindsay Row in Chelsea. There, Whistler was ensconced in a cultural neighborhood that included Dante Gabriel Rossetti (and for a time his housemates, the poet Algernon Swinburne and the novelist George Meredith), Walter Greaves and his brother Henry, among others.

More about this item

Whistler’s House at Old Chelsea, 1863. Etching on paper. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Charles Lee Reese, 1940.

Sir Francis Seymour Haden (British, 1818–1910)

Whistler’s House at Old Chelsea, 1863

etching on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Dr. Charles Lee Reese, 1940

This etching is something of a reversal of the view of the Thames from Whistler’s window produced by Francis Seymour Haden (nearby). Here, Haden depicts Whistler’s house in the Chelsea neighborhood of London at 7 Lindsay Row. Whistler moved there in 1863, the year this print was produced.

More about this item

Brentford Ferry, 1865

Sir Francis Seymour Haden (British, 1818–1910)

Brentford Ferry, 1865

etching on paper

Museums Collections, Gift of Mrs. John Sloan

Francis Seymour Haden, like his brother-in-law Whistler, frequently turned to the Thames as a source of inspiration. Here, Haden evokes a serene sense of the river. Yet, this was a highly traveled commuter spot. He is depicting the landing area for the ferry that conveyed travelers between Brentford and Kew.

More about this item

Coal Barges Unloading, 1872

Walter Greaves (British, 1840–1930)

Coal Barges Unloading, 1872

etching on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

Walter Greaves and his brother Henry were among Whistler’s earliest devotees and assistants. They were the sons of a boatman who made his living on the Thames. Walter Greaves spent a great deal of time rowing with Whistler on the river as he observed life on the Thames and the river’s atmosphere. The Thames was one of the subjects for which Whistler was best known.

This etching depicts two subjects greatly familiar to Whistler, Lindsey Wharf in the Chelsea neighborhood of London where Whistler lived for many years, and Battersea Bridge in the distance, which Whistler depicted in his own art.

More about this item

Old Putney Bridge, 1879

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Old Putney Bridge, 1879

etching and drypoint on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Bridges over the Thames in London were some of Whistler’s favorite subjects in painting and works on paper. The bridge, which connects the districts of Fulham on the north bank and Putney on the south bank, in this print was also the subject of a watercolor. Some of his views of bridges over the river were soft, atmospheric and moody, evoking London fog. Others, as with this example, emphasize detailed line work and convey a sense of the life and work that occurred on and around the Thames.

Bridge motifs are also found in his works from Amsterdam and Venice.

More about this item

Weary, 1863

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Weary, 1863

drypoint and roulette on Japanese paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This is one of Whistler’s most celebrated etchings, depicting one of his most recognizable models, Joanna Hiffernan. She featured in major paintings including Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, 1863, and Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl, 1864 (a period photograph of this painting, on view nearby). Hiffernan lived with Whistler in the 1860s, handling much of his business affairs. Her relaxed, informal pose suggests the intimacy between artist and model. Whistler’s concentration of detail around her shoulders and face highlights her most remarkable feature—her bountiful red hair. The lounging posture evokes a Pre-Raphaelite sensibility and at the time Whistler was close with Dante Gabriel Rossetti, his neighbor in Chelsea. Whistler’s composition can be seen in conversation with more than one of Rossetti’s works.

More about this item

Jane Morris, 1870

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828–1882)

Jane Morris, 1870

pencil on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s drawing of Jane Morris recalls the mood of Whistler’s earlier, famous drypoint, Weary (nearby). The two artists were friends and had a mutual impact on each other’s work. The drawing is also an example of the type of art for which Dante Gabriel Rossetti was best-known, depictions of beautiful women in both literary subjects and modern domestic scenes.

Jane Morris was the wife of William Morris, the renowned designer, writer, and activist associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement. A talented craftsperson herself, she became Rossetti’s principal model and muse in the 1860s and the couple had a love affair. This drawing belonged to the artist’s brother, William Michael Rossetti, an important art critic and supporter of Whistler. William Rossetti testified on Whistler’s behalf in the 1878 trial between Whistler and Ruskin.

More about this item

Portrait of a Lady Wearing a White Cape, c. 1877

Walter Greaves (British, 1846–1930)

Portrait of a Lady Wearing a White Cape, c. 1877

etching with drypoint, retouched with pencil and wash on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

This uniquely retouched print is by one of Whistler’s earliest followers, Walter Greaves. It is a delicate depiction of his sister, Alice Greaves, who was also occasionally a model for Whistler. Significantly, the Greaves family introduced Whistler to the Cremorne Gardens in London. Alice was known to accompany Whistler to the decadent pleasure gardens known for entertainments of all variety, including fireworks displays. These fireworks provided the subject matter for one of Whistler’s most notorious, and nearly abstract paintings, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, 1875.

More about this item

Symphony in White, No. 2, The Little White Girl, 1865

John Robert Parsons (Irish, c. 1826–1909), after James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Symphony in White, No. 2, The Little White Girl, 1865

albumen photograph on mount

Inscribed on mount “To Swinburne. from J. McNeill Whistler” and signed with the “butterfly”

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Whistler’s major painting, originally titled The Little White Girl, completed in 1864, portrays Joanna Hiffernan, (the same model for the etching Weary, nearby) standing in front of the fireplace in the drawing room of Whistler’s house in Lindsey Row. The pose and the accessories—porcelain and a Japanese export market fan—show the artist’s increasing interest in Asian art. The painting inspired Algernon Swinburne to write a poem “Before the Mirror.” This photograph shows it as originally exhibited at the Royal Academy, in a special frame—now lost—with the “verses under a picture” printed on gold paper. The final text appeared in Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads, 1866.

More about this item

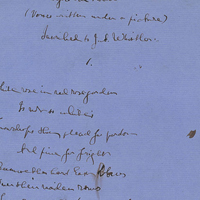

Before the Mirror: Verses under a Picture, Inscribed to J.A. Whistler, 1865

Algernon Charles Swinburne (British, 1837–1909)

Before the Mirror: Verses under a Picture, Inscribed to J.A. Whistler, 1865

autograph manuscript

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This is one of several surviving manuscripts of the poem Algernon Swinburne wrote upon seeing Whistler’s painting Symphony in White, No. 2: The Little White Girl, 1864, in which he added the dedication to Whistler. Swinburne sent an earlier draft to John Ruskin, hoping to interest him in Whistler’s work—without success. Long after their friendship ended, Whistler was still able to praise Swinburne’s poetic tribute, calling it in 1900, “a rare and graceful tribute from the poet to the painter – a noble recognition of a work by the production of a nobler one.”

More about this item

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1860

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828–1882)

Algernon Charles Swinburne, 1860

pencil on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Here, Dante Gabriel Rossetti sensitively depicts young lyric poet Algernon Swinburne, who was often associated with Pre-Raphaelite circles. Swinburne even lived for a time in Rossetti’s house, 16 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, only a few minutes from Whistler’s house. Rossetti, Whistler and Swinburne were constantly in each other’s company in the 1860s.

The relationship between Swinburne and Whistler dissolved in the mid-1880s over Swinburne’s negative review of Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” lecture. By this time, Swinburne, once notorious for his sexually-charged verse, radical politics, and alcoholism, had become a respectable resident of a London suburb, Whistler referring to him as “outsider – Putney” who was not qualified to speak about art.

More about this item

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828–1882). Head of Frederick Leyland, 1879. Pastel on paper. Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (British, 1828–1882)

Head of Frederick Leyland, 1879

pastel on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935

Exhibited Spring 2021

A self-made shipping magnate, Frederick Leyland was also a major art patron. By the early 1870s he assembled a remarkable collection of Italian Renaissance art and paintings by Pre-Raphaelite artists, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who depicted him in this sensitive portrait. Whistler, too, came into Leyland’s orbit and they developed a close association. Leyland commissioned Whistler to make portraits of his family and he purchased the artist’s painting The Princess from the Land of Porcelain.

Two major scandals would fracture the relationship. One involved rumors of an affair between Whistler and Frances Leyland, Frederick’s wife and Whistler’s friend and model. The other involved Whistler’s elaborate—and largely unsolicited—additions to the dining room in Leyland’s London home, known as the Peacock Room.

More about this item

The Peacock Room: Painted for Mr. F. R. Leyland by James McNeill Whistler; Removed in its Entirety from the Late Owner's Residence & Exhibited at Messrs. Obach's Galleries. London: The Galleries, 1904 Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection

Obach Galleries

The Peacock Room: Painted for Mr. F. R. Leyland by James McNeill Whistler; Removed in its Entirety from the Late Owner’s Residence & Exhibited at Messrs. Obach’s Galleries. London: The Galleries, 1904

Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection

In 1876, Frederick Leyland asked Whistler to complete the dining room quickly at his London house when original decorator, Thomas Jeckyll left the project. Instead, Whistler made elaborate interventions for nearly two years, covering the Spanish leather and walnut paneling with blue-green paint and gold gilding, complementing his own painting, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain above the fireplace. When Leyland paid half of what Whistler asked for the unauthorized work, Whistler added a final element: a twelve-foot mural of two fighting peacocks representing artist and patron. The stunning Aesthetic interior became known as the Peacock Room.

This booklet promoted the sale of the Peacock Room when it was dismantled after Leyland’s death. The photographs document Whistler’s decorations and open shelving designed to display Leyland’s collection of ceramics. Charles Lang Freer purchased and moved the room to his home in Detroit. It was later relocated to the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, where it remains today.

More about this item

A Catalogue of Blue and White Nankin Porcelain: Forming the Collection of Sir Henry Thompson, Illustrated by the Autotype Process from Drawings by James Whistler, Esq., and Sir Henry Thompson. London: Ellis and White, 1878

Sir Henry Thompson (British, 1820–1904)

A Catalogue of Blue and White Nankin Porcelain: Forming the Collection of Sir Henry Thompson, Illustrated by the Autotype Process from Drawings by James Whistler, Esq., and Sir Henry Thompson. London: Ellis and White, 1878

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In the 1860s and 1870s, Chinese porcelain and British porcelain modeled on Chinese designs were fashionable among artists and collectors in London. Whistler, Frederick Leyland, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti had collections. Blue and white porcelain became an important feature in Aesthetic Movement interiors, meant to infuse beauty into every aspect of life. Collecting was highly competitive—there are even reports of collectors stealing pieces from one another. This elaborate privately printed book catalogues ceramics owned by Henry Thompson, a rich physician and amateur painter and friend to Whistler in the 1870s. Whistler made sixteen full-page illustrations for this book, as well as a cover design in the style of a Japanese lacquer box.

The catalogue was limited to only 220 copies circulated privately among a select milieu. This copy is inscribed by Thompson to a well-known authority on Chinese porcelain, Stephen Wootton Bushell.

More about this item

Dinner plate, c. 1878

Minton and Company

Dinner plate, c. 1878

painted earthenware

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This plate is an example of a late nineteenth-century form made by Minton and Company, which had been originally founded in 1793 by Thomas Minton. The design was derived from Chinese export porcelain, which had become popular in England. Both Whistler and his patron Frederick Leyland were known for their love of blue and white porcelain. The Peacock Room in Leyland’s London home was filled with open shelving to display his extensive collection of porcelain.

More about this itemThe Butterfly Goes to Court

Men of the Day No. 40: “The Realisation of the Ideal,” 1872

Adriano Cecioni (Italian, 1836–1886)

Men of the Day No. 40: “The Realisation of the Ideal,” 1872

color lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

John Ruskin was a prominent social theorist and the foremost art historian and critic of Victorian Britain. He attacked Whistler from a position of considerable authority, having been appointed the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford University, a position that he held from 1869 until 1878. Captioned “The Realisation of the Ideal,” this caricature from Vanity Fair simultaneously mocks Ruskin’s less-than-ideal rigid and awkward appearance and references his philosophies regarding society and art. Ruskin believed that art had a moral purpose and should be used to uplift society, a philosophy that was in conflict with Whistler’s view that art was, foremost, an arrangement of visual elements.

More about this item

A Symphony, 1878

Leslie Matthew Ward (known as Spy), (British, 1851–1922)

A Symphony, 1878

color lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This caricature of Whistler was published in Vanity Fair in January of 1878, a month after John Ruskin’s counsel filed the first official response to Whistler’s libel lawsuit. It contains many of the characteristic elements in portraits of Whistler, including his monocle, walking stick, cigarette, and the prominent lock of white hair that protrudes from his hat. The caricature was accompanied by a brief biography that addressed Whistler’s artistic theories. In it, the anonymous author defended Whistler’s art in language that would be repeated during the trial. “He has been accused of not finishing his pictures,” the author wrote, “but ‘finish’ is a word that has been abused to convey the more apparent absence of a conventional amount of labour which he rejects…and replaces by his assurance that he has done the work when he has done with it.”

More about this item

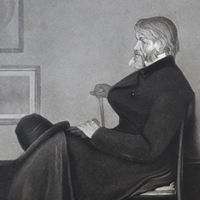

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2, Thomas Carlyle, 1878

Richard Josey (British, 1840 or 1841–1906), after James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 2, Thomas Carlyle, 1878

mezzotint on paper, London: Graves

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Oscar Wilde called the portrait of the Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle the “one really good picture” among the paintings that Whistler exhibited at the controversial Grosvenor Gallery exhibition in 1877, which led to the legal dispute with John Ruskin. In pose and mood, the composition reflects Whistler’s well-known portrait of his mother.

This mezzotint reproduction was made “under the immediate supervision of the painter.” It was produced in September 1878, shortly before the Whistler v. Ruskin trial began.

More about this item

Notes for The Stones of Venice, c. 1850

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900)

Notes for The Stones of Venice, c. 1850

autograph manuscript with sketches

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This sheet contains notes and sketches that John Ruskin used when preparing his multivolume architectural treatise, The Stones of Venice. In it, Ruskin questions the relationship between art and society, arguing that the decline in Venice’s morality—manifested in its art and architecture—presents a warning for England. Ruskin’s opposition to Whistler’s art was an extension of these views. He believed in the moral value of art and railed against what he saw as amorality and consumerism in Whistler’s work.

More about this item

Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain. London: Printed for the author by Smith, Elder & Co. ... and sold only by Mr. G. Allen ..., 1871–1884

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900)

Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain. London: Printed for the author by Smith, Elder & Co. … and sold only by Mr. G. Allen …, 1871–1884

Special Collections

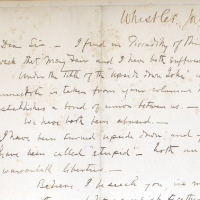

John Ruskin launched his attack on Whistler in July 1877 in letter 79 of Fors Clavigera, his series of polemical pamphlets. Appended to a lengthy discussion of the value of labor and money, Ruskin’s discussion of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibition began with favorable comments on artworks by Edward Burne-Jones in the exhibition. Turning his attention to Whistler, whom he negatively contrasted with Burne-Jones, Ruskin wrote:

“For Mr. Whistler’s own sake, no less than the protection of the purchaser, Sir Coutts Lindsay ought not to have admitted work into the gallery in which the ill-educated conceit of the artist so nearly approached the aspect of willful imposture. I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

Several London newspapers reported Ruskin’s statement, bringing it to Whistler’s attention.

More about this item

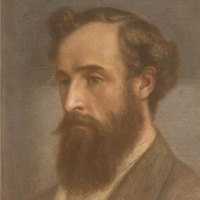

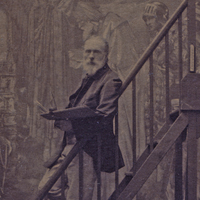

Edward Burne-Jones, c. 1890

Barbara Leighton (British, 1870–1952)

Edward Burne-Jones, c. 1890

platinum print cabinet card

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Edward Burne-Jones was the star witness on Ruskin’s behalf in the Whistler v. Ruskin trial. This photograph shows him at work on the large watercolor painting The Star of Bethlehem. Relatively little is known about the photographer, Barbara Leighton. The daughter of a Conservative politician, she was especially known for her portraits of other artists.

More about this item![Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2021/03/Burne-Jones-ruskin-thumb.jpg )

Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]

Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898)

Autograph letter signed to John Ruskin, 5 November [1878]

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

NEW ACQUISITION

In early November 1878 John Ruskin asked Edward Burne-Jones to testify on his behalf at the upcoming Whistler v. Ruskin trial. Burne-Jones answered him in this letter, emotionally proclaiming his support for Ruskin in a stream-of-consciousness style of communication. Part of the letter reads, “if that advertising Yankee quack teases you I’ll kill him. I thought perhaps it was over. I’ll help in any way that I am told – turn up at a court like Mr. Winkle if you like – so will [William] Morris – it won’t bother you will it? I want peace for you and rest and friends all about spoiling you….,” adding in a postscript, “I have re-read the bit about your commission to lawyers. But I am to be teased & want it. It’s no teasing – I’ll do anything more than gladly.” Despite Burne-Jones’s uneven testimony at the trial, his correspondence indicates the depth of his support for Ruskin.

More about this item![Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/whistler-ruskin-thumb.jpg )

Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics. London: Chatto & Windus, [1878]

Inscribed by Rosa Corder to Frank Newburn

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Less than a month after the trial ended, Whistler published the first of his infamous brown-paper pamphlets. The seventeen-page volume Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics presents the artist’s view of the trial and its significance. Casting the legal battle in moral terms, the text argues against the role of critics in the art world—a claim that Whistler would continue to make throughout his career. The pamphlet was an immediate success. In the two months after the trial, five editions of the volume appeared, bringing widespread attention to Whistler’s account of what he called “a battle fought for the painters.”

Rosa Corder, an artist and one of Whistler’s models, owned this copy of the pamphlet.

More about this item

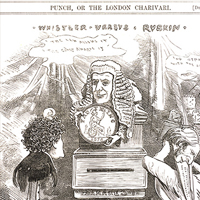

“An Appeal to Law,” in Punch, 7 December 1878

Edward Linley Sambourne (British, 1845–1910)

“An Appeal to Law,” in Punch, 7 December 1878

University of Delaware Library

Showcasing the widespread interest in Whistler and his lawsuit against John Ruskin, this illustration from the popular periodical Punch lampoons both men. The judge, wearing a legal barrister’s wig, presents an oversized farthing to Whistler, highlighting the meager award he received for victory in the legal dispute. Ruskin, identified as the “old pelican in the art wilderness,” looks downward in a way that suggests decapitation. The two-headed snake at the bottom of the illustration indicates the ultimate result of the trial. Labeled “costs,” it extends its tongue in the direction of both Whistler and Ruskin, referencing the legal fees that each side was obligated to pay. Despite his success in the trial, Whistler’s obligation to pay his legal costs led to his financial ruin.

More about this item

James Anderson Rose, 1861

Frederick Sandys (British, 1829–1904)

James Anderson Rose, 1861

black, white, and red chalks on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

As Whistler’s solicitor, James Rose directed the legal strategy used in the Ruskin trial. He retained the barrister John Humffreys Parry to argue the case before the court.

Rose was a close friend and associate of many artists, including Whistler. He assembled a collection of artworks by his friends and clients, which included several paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and a prized collection of Whistler’s prints. This portrait drawing by the Pre-Raphaelite artist (and Whistler associate) Frederick Sandys appears to depict the sitter deep in thought, emphasizing his keen and penetrating mind.

More about this item

Virgil and the Muse of Poetry, c. 1880–1890

Edward Burne-Jones (British, 1833–1898)

Virgil and the Muse of Poetry, c. 1880–1890

watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Edward Burne-Jones was a close friend of John Ruskin and one of the three witnesses who appeared on his behalf at the trial. Of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold—the painting that Ruskin specifically criticized in his review—Burne-Jones testified, “It would be impossible to call it a serious work of art.” One of Burne-Jones’s main complaints about Whistler’s art was its apparent incompleteness. Although he praised Whistler’s use of color, Burne-Jones criticized what he saw as a lack of form and “finish.”

As this watercolor indicates, Burne-Jones frequently depicted medieval and mythological subjects. This is one of a number of artworks that relate to Virgil or his epic poem, The Aeneid. The frame is original and was designed by the artist.

More about this item

Study of a Draped figure for the right-hand figure in The Shulamite, 1864

Albert Joseph Moore (British, 1841–1893)

Study of a Draped figure for the right-hand figure in The Shulamite, 1864

black and white chalks on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

Whistler and Albert Moore first met in 1865, the year after this drawing was made, and the two men developed a lifelong friendship. As one of Whistler’s three witnesses at the Whistler v. Ruskin trial, Moore was the strongest proponent of Whistler’s art during the proceedings. Despite differences in their preferred subject matter, Whistler and Moore shared an aesthetic affinity that celebrated “art for art’s sake.”

Like Whistler, Moore employed meticulous working methods. For each painting, Moore prepared numerous studies of figures and drapery. This characteristic study depicts an early pose, which Moore later modified, for one of the figures in his large 1866 painting, The Shulamite.

More about this itemThe Butterfly in Venice

San Giorgio Maggiore, the Basin of St. Mark's and a Balcony of Casa Contarini-Fasan, 1876. Watercolor over pencil on paper, heightened with gouache with touches of pen and ink. Collection of BNY Mellon.

John Ruskin (British, 1819–1900)

San Giorgio Maggiore, the Basin of St. Mark’s and a Balcony of Casa Contarini-Fasan, 1876

watercolor over pencil on paper, heightened with gouache with touches of pen and ink

Collection of BNY Mellon

For the Victorian public, no figure was more strongly associated with Venice than John Ruskin. He made eleven visits and published numerous books about the city. He also produced drawings that recorded details of Venetian architecture. The Ca’ Contarini-Fasan, the so-called “House of Desdemona,” appears on the left side of the watercolor. In contrast to the loose rendering of the sky and water, Ruskin has carefully pictured the spiral designs on the palace’s famous balconies.

This watercolor was made during Ruskin’s last major trip to Venice. He returned to England in June 1877 and soon published the negative review of Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold that prompted the Whistler v. Ruskin trial. Despite Ruskin’s vitriolic reaction to Whistler’s painting, their art occasionally shared surprisingly similar characteristics, including soft, dissolving atmospheres and a recurring fascination with the details of building facades.

More about this item

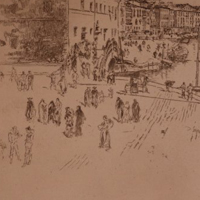

The Riva, No. 2, 1880

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Riva, No. 2, 1880

etching on paper

Museums Collections

Recent Acquisition

Whistler left for Venice in September of 1879, intending to make a dozen etchings on commission from the Fine Art Society. After spending over a year in the city, he produced some four-dozen etchings of Venetian subjects, including close-up renderings of the city’s architecture and its people, as well as more expansive views like this one. As the title suggests, this is one of Whistler’s two depictions of the Riva degli Schiavoni, a waterfront promenade that extends east from the Piazza San Marco. Since Whistler preferred to work directly on his etching plates, this artwork—like all of his Venetian prints—shows the cityscape in reverse.

Whistler likely made this etching from a room at the Casa Jankowitz, where he and his longtime companion Maud Franklin—who was also an artist—rented a room in the summer of 1880. Many of his young associates, including Otto Bacher, rented rooms in the building.

More about this item

St. Mark’s, Venice, 1880

Otto Henry Bacher (American, 1856–1909)

St. Mark’s, Venice, 1880

etching on paper

Museums Collections

In 1880, Whistler befriended a circle of young American artists who were studying in Venice for the summer. Otto Bacher was among this group, many of whom were enamored of the now-notorious Whistler. The two men became close and remained friendly throughout their lives. Following Whistler’s death, Bacher published several articles and a book detailing his time in Venice with Whistler.

Whistler and Bacher shared an interest in depicting everyday life in Venice. In addition to this image of a woman praying at a side altar in the church of San Marco, Bacher depicted Venetian gondoliers, bead-stringers, and net-makers.

More about this item

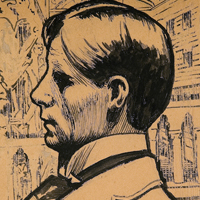

Self-portrait, 1897

Walter Richard Sickert (British, 1860–1942)

Self-portrait, 1897

ink, watercolor, and wash on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Like Joseph Pennell, Walter Sickert’s interest in Venice may be attributed to Whistler. Sickert once worked as Whistler’s assistant and was a longtime follower. After first visiting the city in 1894, Sickert made a handful of visits between 1895 and 1904, each of which lasted several months or more. In this self-portrait, Sickert positions himself in front of the Bridge of Sighs, one of Venice’s most recognizable landmarks.

More about this item

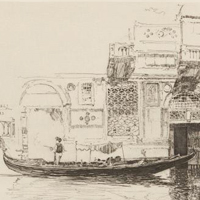

A Watergate in Venice, 1883. Etching on paper. Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978.

Joseph Pennell (American, 1857–1926)

A Watergate in Venice, 1883

etching on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1978

Exhibited Spring 2021

In 1881, Joseph Pennell encountered Whistler’s Venetian etchings in an exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. This print shows the extent of Whistler’s influence upon Pennell. Both the subject—an intimate glimpse of a fleeting moment in everyday Venetian life—and the style are indebted to Whistler. Whistler was particularly drawn to palaces with elaborate grates surrounding the doors and windows. Pennell would have seen one such print, The Doorway, in Philadelphia, which likely influenced Pennell’s subject matter.

More about this item

![Etchings & Drypoints: Venice, Second Series. [London]: J. M. Whistler, 1883. Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/etchings-drypoints-thumb.jpg )

Etchings & Drypoints: Venice, Second Series. [London]: J. M. Whistler, 1883. Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection.

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Etchings & Drypoints: Venice, Second Series. [London]: J. M. Whistler, 1883

Courtesy, the Winterthur Library: Printed Book and Periodical Collection

Shortly after his return to London, Whistler exhibited a dozen Venetian etchings at the Fine Art Society. Additional exhibitions of Venetian pastels and etchings occurred in the following years. For the second exhibition of Venetian etchings in 1883, Whistler prepared a catalogue that foretold The Gentle Art of Making Enemies and other publications. In it, Whistler extracted selections from critical reviews, to which he appended witty responses.

Among the etchings included in the 1883 exhibition were Riva, No. 2 and Nocturne: Furnace, both of which are on view in this exhibition.

More about this itemThe Butterfly and Aestheticism

La Robe Rouge, 1894

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

La Robe Rouge, 1894

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Beatrix Whistler (née Beatrice Philip) was an artist and designer who met Whistler through her first husband, the architect Edward William Godwin. In La Robe Rouge, she reclines in an armchair in the drawing room of their Parisian house. The original drawing was done on thin paper, which was sent to Whistler’s printer, Thomas R. Way, who transferred the image onto a lithographic stone for printing. It was one of many portraits Whistler made of his wife in the early 1890s as they traveled between London and Paris seeking improvement for her poor health.

More about this item

Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1894

Beatrix Whistler (British, 1857–1896)

Count Robert de Montesquiou, 1894

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

For many years scholars and collectors believed this lithograph was by James McNeill Whistler, but recent research has convincingly suggested that it was actually drawn by his wife Beatrix. Her print is based on a portrait of the French aristocrat, dandy, collector, and arch-aesthete Count Robert de Montesquiou, painted by her husband in 1892 (The Frick Collection). Both James and Beatrix set to work on a lithographic version of the portrait for a French art journal in the summer of 1894. However, neither artist was satisfied with the results, so the portraits were never published. This proof print is a rare example of Beatrix Whistler’s work held outside of the Whistler collection at the University of Glasgow.

More about this item

The Thames, 1896

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Thames, 1896

lithotint with scraping on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

One of Whistler’s most complex and evocative nocturnes, The Thames was also the last image he created while living at London’s Savoy Hotel with his wife Beatrix in early 1896. Many of Whistler’s lithographs from this period were printed using transfer paper, but he drew this image directly on a stone, which his printers had prepared and delivered to the hotel. Whistler worked on the stone on his balcony for several weeks, eventually capturing the effects of the silvery mist and delicate lights of the Thames at dusk. At this point Beatrix was quite ill with cancer, but when possible her bed was moved near the windows so that she too could take in the view of the river and the city. She died in May 1896.

More about this itemWhistler and Wilde

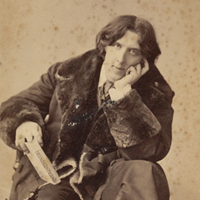

It was almost inevitable that Whistler’s friendship with writer Oscar Wilde would end with enmity. The men were too much alike: wits, dandies, self-promoters, and outsiders—one American, one Irish—clamoring for attention. A leading proponent of the Aesthetic Movement, Wilde is best known for his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), his comic play The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), and the 1895 trial that led to his imprisonment for homosexuality.

When Wilde met Whistler around 1879, he quickly fashioned himself as the artist’s disciple. As his popularity eclipsed Whistler’s in the 1880s, a battle of wits began to play out in private and in the press. Whistler grew to resent the ways Wilde had adopted not only his ideas, but also elements of his speech and style. Once, after hearing Whistler make a clever remark at a party, Wilde exclaimed that he wished that he had said it. Whistler retorted “You will, Oscar, you will.” Despite their ultimate falling out, Whistler and Wilde’s repartee helped to shape the public’s perception of both men.

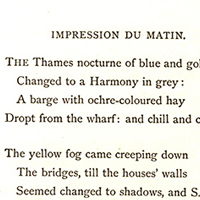

Poems. London: David Bogue, 1881

Oscar Wilde (Irish, 1854–1900)

Poems. London: David Bogue, 1881

Author’s presentation copy to Violet Fane, with original manuscript poem

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Oscar Wilde’s volume of verse reflects the significance of writers and artists associated with Aestheticism, including Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Swinburne, to his writing. Wilde’s admiration for Whistler is apparent in the poem “Impression du Matin.” The opening lines evoke the combination of music and color Whistler sought to convey in his work:

The Thames nocturne of blue and gold

Changed to a Harmony in grey

Wilde gave this copy of Poems to the writer Violet Fane (pseudonym of Mary Singleton), who was also a friend of Whistler.

More about this item

Oscar Wilde, 1882

Napoleon Sarony (American, b. Canada, 1821–1896)

Oscar Wilde, 1882

albumen cabinet card

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In January 1882, shortly after arriving in America for a year-long lecture tour, Oscar Wilde posed for a series of photographs in the New York studio of Napoleon Sarony. The portraits were used to advertise his lectures, which were intended to promote Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera Patience. Like Whistler, Wilde purposefully shaped his image by adopting distinctive dress. His velvet jacket, knee breeches, and silk stockings quickly became fodder for caricatures and were adopted by his admirers. In this photograph he is holding a volume of his first book, Poems (1881). The influence of Whistler was equally evident in the substance of Wilde’s lectures, which addressed art, design, and Aesthetic theory.

More about this item![Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/53_Whistler_James_Ten_oclock_thumb.jpg )

Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Mr. Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock.” London: [Chatto and Windus], 1888

Author’s presentation copy to Beatrix Whistler, accompanied by a printed invitation to the lecture

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

On February 20, 1885, Whistler delivered his “Ten O’Clock” lecture, an hour-long evening talk in London later published in this volume. He carefully orchestrated the event, from the unusual time to the composition of the audience, which included fashionable artists, patrons, and writers. Whistler challenged contemporary ideas about art, arguing that it should not seek to copy nature, have literary meaning, or serve a social purpose. The talk was also a rebuke to Oscar Wilde, who watched from the third row. Whistler felt Wilde had plagiarized his artistic theories. Wilde responded to the lecture with critical articles in the Pall Mall Gazette, setting off a series of acerbic exchanges in the press that led to further estrangement.

Whistler inscribed this copy of the published lecture to his wife Beatrix using her pet name “To my ‘luck’” and signed it with his signature butterfly.

More about this item

Wilde v. Whistler: Being an Acrimonious Correspondence on Art between Oscar Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. London: Privately Printed, 1906

Oscar Wilde (Irish, 1854–1900)

Wilde v. Whistler: Being an Acrimonious Correspondence on Art between Oscar Wilde and James McNeill Whistler. London: Privately Printed, 1906

Special Collections

Based on the format of Whistler’s pamphlets, Wilde v. Whistler offers insight into the notorious feud between the writer and the artist. Wilde’s canny publisher, Leonard Smithers, produced this small volume as a rare collector’s item, taking advantage of the burgeoning market for both Wilde and Whistler after their deaths. The contents were nothing new, comprising letters and reviews published in London newspapers between 1885 and 1890. The book begins with Wilde’s negative review of Whistler’s “Ten O’Clock” lecture and chronicles their ongoing clashes in the press.

More about this item

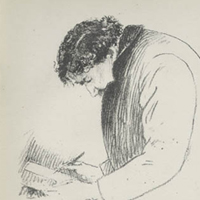

Autograph letter signed to G. F. Scotson-Clark, 9 August 1891

Aubrey Beardsley (British, 1872–1898)

Autograph letter signed to G. F. Scotson-Clark, 9 August 1891

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Aubrey Beardsley was a leading English illustrator of the 1890s and a central figure in the Decadent Movement. He is best known for his striking illustrations for Oscar Wilde’s play, Salome. In this letter to a former school friend, the nineteen-year-old artist indicates his great admiration for Whistler and the Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Painter’s Mother. He had recently seen the painting at the Society of Portrait Painters exhibition in London. Beardsley describes Whistler’s work as “a truly glorious, indescribable, mysterious & evasive picture…the curtain marvellously painted, the border shining with wonderful silver notes.” Beardsley includes a sketch of himself in the same pose as the seated figure of Whistler’s mother, going as far as to sign it with an imitation of Whistler’s butterfly.

More about this item

Sketches of “Patience” at the Opera Comique, from Punch, June 17, 1881

Harry Furniss (British, 1854–1925)

Sketches of “Patience” at the Opera Comique, from Punch, June 17, 1881

hand-colored lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Recent Acquisition

This print by illustrator Harry Furniss records scenes from the opening night of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera, Patience, which satirized the Aesthetic Movement. Published in the popular magazine Punch, the lithograph includes images of the actor George Grossmith in the role of the “fleshly” poet Reginald Bunthorne, who sings:

Am I alone, And unobserved? I am!

Then let me own I’m an aesthetic sham!

With his monocle and dark curly hair with a white streak, Bunthorne’s costume clearly references Whistler, but his knee breeches are reminiscent of Wilde. The show was a commercial success and was one of the few satirical depictions of their identities that both Whistler and Wilde enjoyed. Patience helped ensure that the two men were tied together in the public eye as exponents of Aestheticism.

More about this item

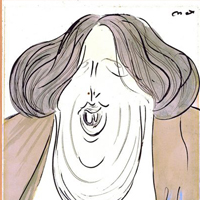

Oscar Wilde, late 1890s

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Oscar Wilde, late 1890s

pencil and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The celebrated caricaturist Max Beerbohm depicted Oscar Wilde repeatedly over the course of his career, capturing the controversial writer’s evolving public image and physical appearance. Although Beerbohm knew and greatly admired Wilde, his caricatures often cruelly exaggerated Wilde’s features and emphasized his increasingly corpulent body. When this caricature was produced in the late 1890s, Wilde had reached the height of fame and success with his plays and had met a swift downfall following his conviction for “gross indecency.”

Although their friendship was over, Whistler followed the legal proceedings and found the prison sentence—two years of hard labor—too harsh.

More about this item

Maudle on the Choice of a Profession, 1881

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Maudle on the Choice of a Profession, 1881

ink on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Illustrator and author, George Du Maurier, was a long-term contributor to the satirical magazine Punch, where his drawings critiqued Victorian society. Du Maurier helped to create an interest in Aestheticism through his mocking cartoons, many of which featured the characters Maudle and Postlethwaite, who resembled Wilde and Whistler. In this drawing Maudle is shown leaning in to speak to a woman at a fashionable event. The caption clarifies that the Wilde-like figure is arguing that existing beautifully is occupation enough for a young man, an exaggeration of Aesthetic values:

Maudle: “How consummately lovely your son is, Mrs. Brown!”

Mrs. B (a Philistine from the country): “What? He’s a nice, manly boy, if you mean that Mr. Maudle. He has just left school you know and wishes to be an artist.”

M.: “Why should he be an artist?”

Mrs. B.: “Well, he must be something?”

M.: “Why should he be anything — why not let him remain for ever content to exist Beautifully!” (Mrs. B. determines that at all events her son shall not study art under Maudle.)

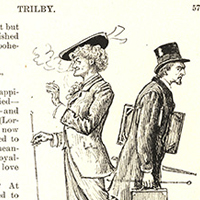

Trilby, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1894

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Trilby, in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1894

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Trilby was one of the most popular novels of the Victorian era. Set in Paris of the 1850s, it was based on George Du Maurier’s experiences when he and Whistler were students in the studio of painter Charles Gleyre. By 1894, when the story first appeared in installments in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, the once close relationship between Whistler and Du Maurier had grown distant. Whistler was outraged to discover an unflattering and thinly veiled portrait of himself—pictorial as well as textual—in the story. The character Joe Sibley, described as a lazy, pompous, and eccentric American art student, was easily identifiable. Whistler threatened legal action unless Harper’s removed all references to Sibley. The dispute drew attention from the British and American press and helped make Trilby a sensation—with Whistler’s name permanently attached to the story. When the installments were published as a book, Sibley was removed completely.

More about this item

Studies for “Punch,” 1893–1895

George Du Maurier (British, b. France, 1834–1896)

Studies for “Punch,” 1893–1895

album of drawings and autograph manuscripts

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This album of George Du Maurier’s sketches contains a portion of the manuscript of Trilby concerning Joe Sibley—an unflattering character based on Whistler. It also contains a draft of a letter from Du Maurier to Whistler in which he offers regrets for any offense given. Du Maurier writes that, “None of my characters were intended for real portraits. You were quite mistaken about my motives. I hope it is no libel to say that I have never been [jealous?] of you; nor (as you seem to think) afraid—nor have I ever borne you any ill will.” The publisher, Harper’s, printed a public apology to Whistler, but it is not clear if a version of this more personal missive was ever sent.

More about this itemThe Butterfly’s Legacy

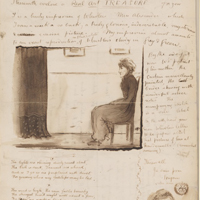

Sketch of Whistler When He was Retouching a Stone, 1895

Thomas Robert Way (British, 1861–1913)

Sketch of Whistler When He was Retouching a Stone, 1895

lithograph on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Thomas R. Way was the son of Whistler’s printer, Thomas Way. Over the course of their long relationship with Whistler, the Ways printed and helped to prepare Whistler’s prints, produced catalogues of Whistler’s major exhibitions, and authored texts on lithography and Whistler’s art. Significantly, the Ways introduced Whistler to various lithographic techniques and collaborated with him on lithographic projects.

Despite his contentious public persona, Whistler was meticulous about his art. Here Way shows him standing, deep in concentration, as he makes changes on a lithographic stone.

Less than a year after this portrait was made, a number of conflicts, including Whistler’s desire to control his publicity and disputes about the ownership of artworks in Way’s possession, led to the end of the relationship between Whistler and the Ways.

More about this item

The Smith’s Yard, 1895

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Smith’s Yard, 1895

lithograph on paper

Museums Collections

Whistler produced lithographs throughout his career, but he devoted particular attention to the medium in the 1890s. He was especially important in advocating for the elevation of lithography from its association with commercial use to the realm of fine art.

Whistler spent the autumn of 1895 in Lyme Regis, a resort town on the English coast. The blacksmith’s yard in this print was not far from Whistler’s studio, and Whistler made numerous depictions of the smith, his property, and members of his family. Scenes of everyday life and labor are seen from the beginning of Whistler’s career to his last decade of work.

More about this item

St. Jacques, Dieppe from the Rue Pecquet, c. 1900

Walter Richard Sickert (British, 1860–1942)

St. Jacques, Dieppe from the Rue Pecquet, c. 1900

ink, charcoal, and wash on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

In 1885, Whistler joined his pupil and assistant Walter Sickert at the French resort town of Dieppe. The experience marked the beginning of Sickert’s decades-long fascination with Dieppe. The Gothic church of St. Jacques particularly appealed to Sickert, who depicted it over two dozen times. The loose, shadowy rendering of this drawing is reminiscent of Whistler’s cityscapes and Whistler’s interest in exploring the aesthetic potential of complex building facades.

Sickert’s interest in Dieppe would outlast his relationship with his former artistic mentor. After a series of disputes, the two artists became estranged in 1896.

More about this item

Ida Nettleship, 1899–1900

Augustus John (Welsh, 1878–1961)

Ida Nettleship, 1899–1900

pencil on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

As a young artist, Ida Nettleship studied at Whistler’s Académie Carmen in Paris. Here she is depicted in a pencil portrait by the Welsh painter Augustus John, whom she would marry in 1901. The composition is reminiscent of Whistler’s Symphony in White No. 2: The Little White Girl. (A photograph of that painting, signed by Whistler, is on view in the exhibition.) Yet while the subject of Whistler’s painting gazes dreamily into a mirror, Nettleship turns to look over her shoulder, directing her lively expression outward.

More about this item

Seated Cat, 1907

Gwen John (Welsh, 1876–1939)

Seated Cat, 1907

watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Gwen John is one of the best-known artists who studied at the Académie Carmen, the art school that Whistler founded in Paris. Her brother Augustus John described Whistler’s influence on his sister: “With some talented student friends she passed some time in Paris under the tutelage of Whistler. It was thus she arrived at that careful methodicity, selective taste and subtlety of tone which she never abandoned.”

Among John’s favorite subjects were her cats, which she frequently depicted in watercolors.

More about this item

Nocturne, Furnace, 1879–1880

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Nocturne, Furnace, 1879–1880

etching on paper

Special Collections, A. J. Rosenfeld Etchings Collection

Whistler frequently incorporated views through doorways or other openings into his prints. This etching, made during the artist’s 1879–1880 sojourn in Venice, shows the canal door of a small workshop. The bright light from the furnace illuminates the worker who stands, wearing an apron, in the middle of the doorway. Dark, hatched lines around the doorway reinforce the nocturnal setting. The distinctive prow of a gondola floats in the water at left. Like many of Whistler’s etchings, this composition combines elements of detail at the center with a dissolving, ambiguous atmosphere at the edges.

This print and Riva, No. 2 (on view nearby) were published in Whistler’s “Second Venice Set” in 1886.

More about this item

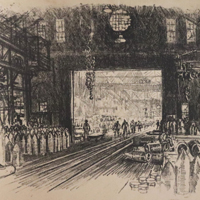

Shell Factory, No. 2: from Shop to Shop, 1917

Joseph Pennell (American, 1857–1926)

Shell Factory, No. 2: from Shop to Shop, 1917

lithograph on paper

Museums Collections

Joseph Pennell was an artist, writer, and—along with his wife, Elizabeth—a friend and staunch supporter of Whistler and his art. This print shows the enduring impact of Whistler’s style and printmaking strategies on Pennell’s own work. Although it was made over a decade after Whistler’s death, the print, from Pennell’s series depicting the labor of war in Britain and the United States, utilizes the same compositional strategy seen in Whistler’s Nocturne, Furnace (nearby). Both Pennell and Whistler also shared an interest in labor as a subject.

More about this itemWhistler and Max Beerbohm

Max Beerbohm was among the most significant caricaturists at the turn of the century. He met Whistler in London in 1896 and became engaged in a verbal exchange that was played out in the press. Mocking Whistler for his vanity, Beerbohm wrote, “[w]hile other great painters have…been tearing their hair, he has been arranging his before a mirror.” However, Beerbohm nonetheless appreciated the older artist’s writing, telling a friend that Whistler’s art criticism gave him “keenest delight.” He produced several caricatures of Whistler, both during and after the artist’s lifetime.

Autograph letter signed to Eric Parker, c. 18 July 1903

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Autograph letter signed to Eric Parker, c. 18 July 1903

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This letter references The Gentle Art of Making Enemies and asks if the recipient saw the headline in the Sun that linked the deaths of Whistler and Sir Peter Edlin, the judge who presided at the litigation William Eden brought against the artist. Of the connection, Beerbohm wrote, “I think a certain monocled cherub must have chuckled at it.” Whistler’s legal battles were clearly of interest to Beerbohm, who depicted the artist’s contentious legal proceedings in several caricatures.

More about this item

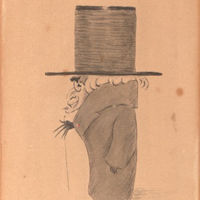

Mr. James Whistler, c. 1900

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Mr. James Whistler, c. 1900

ink and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This small caricature shows Whistler, buttoned up in an oversized coat, wearing a comically large hat. That Whistler appears swamped in his garments may be a reference to his slight figure. The artist wears a monocle and is depicted with a tiny red dot on his coat—likely a mocking reference to the medal that Whistler was frequently depicted wearing after being awarded the French Legion of Honor in 1889.

More about this item

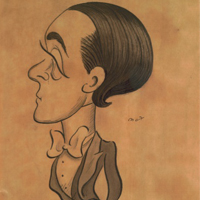

Self-caricature, c. 1900

Max Beerbohm (British, 1872–1956)

Self-caricature, c. 1900

ink and watercolor on paper

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Made around the same time as his caricature of Whistler on view nearby, this self-portrait shows Max Beerbohm with similar accessories, including an exaggerated top hat, long coat, and walking stick. Beerbohm fashioned himself a dandy in the mold of Whistler or Oscar Wilde.

More about this item

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. London: William Heinemann, 1890

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. London: William Heinemann, 1890

Inscribed by Whistler to Ellen Sickert

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

The publication history of Whistler’s notorious book The Gentle Art of Making Enemies is fraught with controversy and uproar—just like its contents. The project originated with an American journalist, Sheridan Ford, who proposed a book containing Whistler’s extensive published newspaper correspondence. After Whistler abruptly ended the project, Ford published the book anyway. Whistler sought legal intervention to stop the book’s distribution and determined to publish his own edition of The Gentle Art.

Whistler presented this inscribed first edition of the book to the artist Ellen (“Nellie”) Sickert, the wife of Whistler’s assistant and follower, Walter Sickert.

More about this item

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. A New Edition. London: William Heinemann, 1892

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

The Gentle Art of Making Enemies: as Pleasingly Exemplified in Many Instances, wherein the Serious Ones of this Earth, Carefully Exasperated, have been Prettily Spurred on to Unseemliness and Indiscretion, while Overcome by an Undue Sense of Right. A New Edition. London: William Heinemann, 1892

Inscribed by Whistler to George Moore

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

Whistler approached the publication of The Gentle Art of Making Enemies with the same care that he devoted to his art. He used quality paper and placed his unique butterflies in precise locations on the pages to interact with the text. The pared-down elegance of the book’s typography and its off-centered title page would greatly influence turn-of-the-century bookmaking. Beyond merely highlighting Whistler’s verbal battles with his enemies, the book presents Whistler’s aesthetic philosophy as articulated in the Ruskin trial and the “Ten O’Clock” lecture.

Whistler presented this expanded later edition of the book to the Irish novelist, critic, and champion of the Impressionists, George Moore—a Whistler frenemy.

More about this item

Cope's Mixture: Selected from his Tobacco Plant. Liverpool: At the Office of Cope's "Tobacco Plant," 1893. No. 8 of Cope's Smoke-Room Booklets

Cope’s Mixture: Selected from his Tobacco Plant. Liverpool: At the Office of Cope’s “Tobacco Plant,” 1893. No. 8 of Cope’s Smoke-Room Booklets

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This advertisement from a Liverpool tobacco company shows how successfully Whistler’s Gentle Art of Making Enemies became a part of British popular culture. Although Whistler’s name does not appear, the reference is unmistakable: at the top of the page, a caricature of the artist—complete with monocle and pipe—takes the form of a butterfly, complete with a stinger.

More about this item![Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/whistler/wp-content/uploads/sites/227/2020/07/74_Whistler_James_Eden_vs_Whistler_thumb.jpg )

Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]

James McNeill Whistler (American, 1834–1903)

Eden versus Whistler: The Baronet & the Butterfly, A Valentine without a Verdict. Paris: Louis-Henry May, [1899]

Inscribed by Whistler to his sister, Deborah Haden

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection