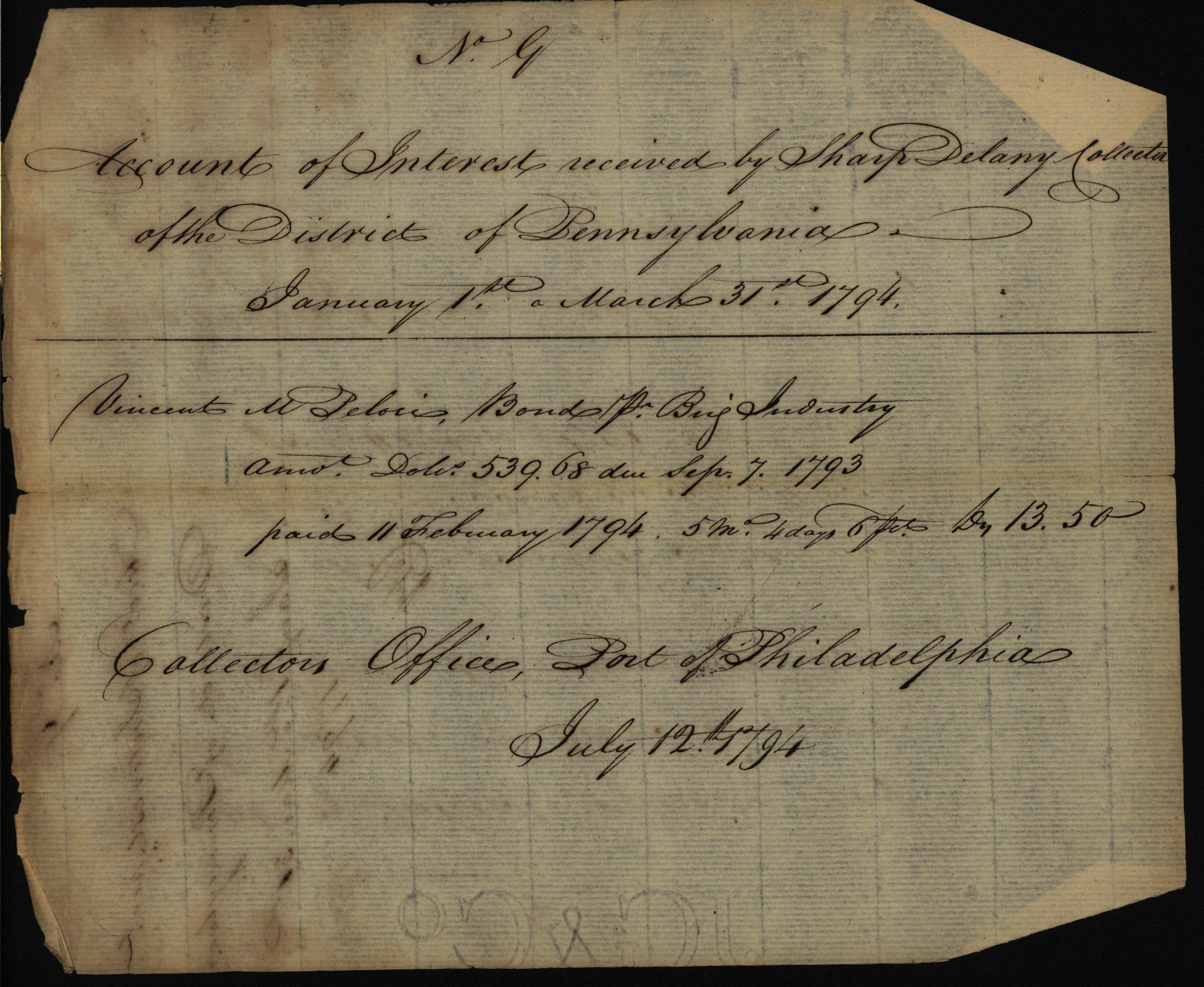

Following the American Revolution, and prior to the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, each state attempted to set up its own customs service. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania established the Custom House in Philadelphia in 1784, appointing Sharp Delaney as its first collector.

However, the adoption of the Constitution transferred the power to levy import tariffs from the states to the federal government and gave Congress control of international trade relations. The United States Customs Service was established on July 31, 1789 as a branch of the Treasury Department. Initially, Congress created 59 customs districts in 11 states, each with a customs collector and a naval officer. Many larger ports, like Philadelphia, also employed surveyors, inspectors, weighers, gaugers, and revenue-cutter crews, all reporting to the customs collector. Delaney stayed on at the port of Philadelphia as the district collector under the U.S. Customs Service.

The Customs Service was instituted to control shipping, enforce laws regulating exports and imports, register and license American vessels, and prevent smuggling. However, its primary function was to generate much-needed revenue for the new federal government. By 1860, the U.S. Customs Service was responsible for collecting nearly half of the revenue taken in by the federal government.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the U.S. Customs Service’s gained additional responsibilities, including issuing regulatory documents, collecting passenger lists from vessels arriving from foreign ports, holding imported goods in bonded warehouses until duties were paid, keeping official records on the sale of vessels, and collecting hospital fees from arriving vessels to fund the Marine Hospital for sick and disabled seamen. The expansion and specialization of the Customs Service also contributed to the rise of brokers, intermediaries who transacted customs house business on behalf of importers and exporters.