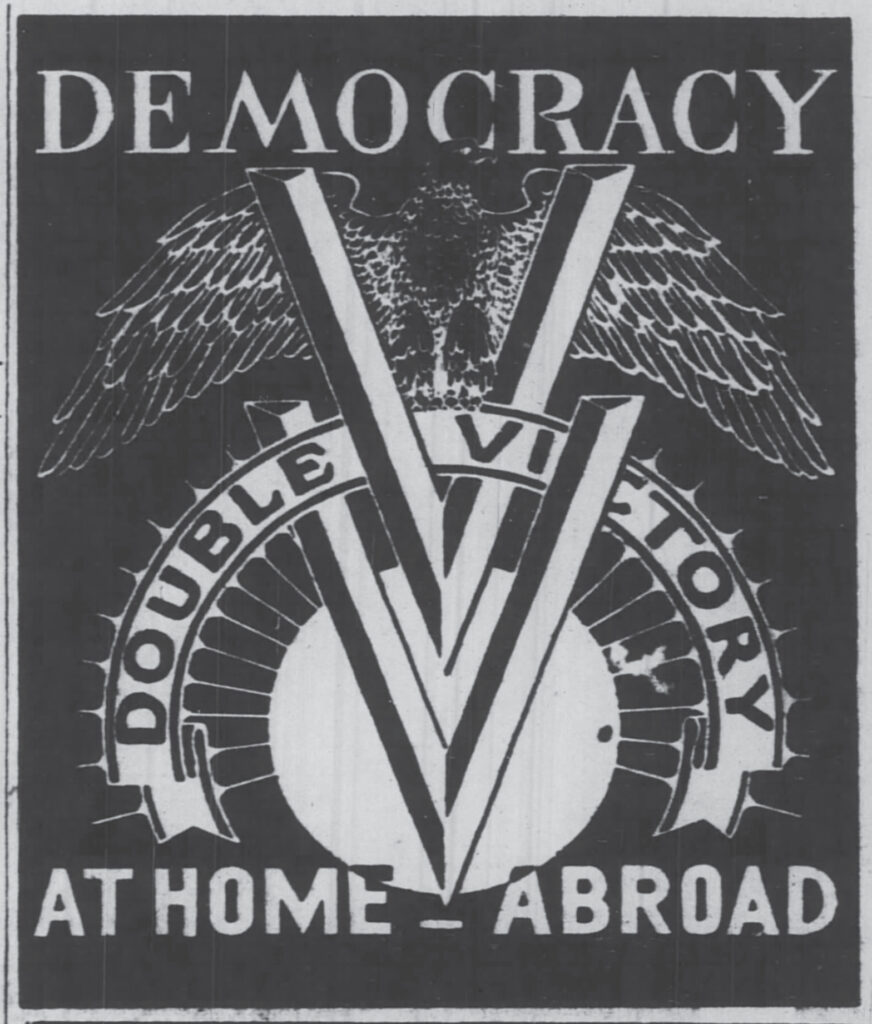

During the World War II era, Langston Hughes took on a prominent role as an activist. Hughes used his work to join a movement known as the Double V Campaign. The Double V Campaign started out as a slogan designed by the historically Black newspaper, The Pittsburgh Courier. The idea behind the slogan was that while African American soldiers fought for freedom abroad, the Double V Campaign fought for freedom for African Americans at home. The campaign promoted “double” victory that meant defeating fascism and Nazism abroad, while also defeating Jim Crow and inequality at home. The campaign pointed out the hypocrisy of the United States’ involvement in World War II, when freedom in America was only accessible for a white population. The movement also fought for the end to segregation and discrimination in the armed forces. Hughes used his art and fame to bring attention to the campaign during this period. This included songs, poems, radio broadcasts, and newspaper articles, some of which are featured in the Langston Hughes ephemera collection.

Program for “The Ivy Leaf Club of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority Presents Langston Hughes,” April 4, 1944, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware

On a Tuesday evening during World War II, Langston Hughes joined the Ivy Leaf Club of the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, Inc. with a message on his view on the war. Alpha Kappa Alpha was the first intercollegiate African American sorority, founded in 1908 at Howard University. The program presents Hughes as a poet whose work focuses on “the every day happenings, the idealism, the high aspirations of the new American Negro.” However, Hughes was not only reading his poetry, but also presented some of his musical pieces, among them “Freedom Road.”

“Freedom Road” was one of the pieces Hughes wrote during World War II with the Double V Campaign’s mantra in mind. The song featured a patriotic tone of fighting against Hitler and fascism, while also making it clear that at the same time there must be freedom for Black soldiers at home. The lyrics read “United we stand, divided we fall, Let’s make this land safe for one and all. I’ve got a message, and you know it’s right, Black and white together unite and fight.”

When “Freedom Road” first came out on the radio, Hughes wrote in a letter to Noël Sullivan, wealthy philanthropist and benefactor to Hughes, that the song stemmed from his concerns about how Black soldiers were being treated in the South. He wrote that “the lower Southern elements resent colored boys in uniform and so go out of their way often to be rude and unpleasant.” He pointed out that it reflected poorly on the U.S. government and the War Department that even as they fought for freedom abroad, “they [could not] protect their soldiers in certain parts of our own country” (quoted in Rampersad 244). Hughes finished the letter by saying that he had a lot more to say but “Freedom Road [was] the best [he] could do.”

It is clear why Hughes would have wanted this song performed for the audience at the Ivy Leaf Club: he was on a journey to share the idea that twenty-eight months into the U.S.’s involvement in World War II, the country should not just be looking at victory and freedom abroad, but also at home.

-Maddy Starling (UD Summer Scholar 2021)

Program for the Committee of the Plymouth Congregational Church's “Plymouth Lecture Series 7th Anniversary Presents Langston Hughes with the Dupre Victorian Chorus,” May 5, 1944, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware

This 11-piece program highlights the Plymouth Lecture Series in Detroit, Michigan featuring Langston Hughes. The fourth page includes an introduction to the lecture series and its rationale: “In these days when our community and the nation have been seeking a constructive way out in building human relations, this Lecture Series has been able to render a real service.” By featuring Langston Hughes, the committee for this lecture series sought his opinions on how the country could better build human relations, including Hughes’ opinions on the war and civil rights.

According to the program, Hughes performed six pieces for this audience which were interspersed with performances by the DuPre’ Victorian Chorus, advertised as one of the finest choral organizations in Detroit. Hughes’ selections included many pieces reflecting on the beauty and strength of African Americans, such as “Beauty of Negro Women” and “Strength of Negro Men,” but after the intermission, Hughes changed the tone of his lecture by switching to two pieces discussing the African American struggle for freedom. One of these pieces was his poem “Freedom’s Plow.”

“Freedom’s Plow” was originally published in April of 1943 in the midst of World War II. The poem tells the story of slavery, while also critiquing the unfinished American dream. Hughes invoked a song sung amongst enslaved people about keeping one’s hands on the plow and holding on until freedom would one day come. He wrote about how the end of the Civil War did not bring about the freedom and equality they had hoped for, so they must keep holding on to the plow and know that they cannot stop until everyone knows freedom. Hughes repeated words engraved into the backbone of America such as “Brotherhood,” “Democracy,” “Freedom,” and phrases like “All men are created equal.” He asks, “Who owns those words?” and answers “Americans! / Who is American? You, me!/ We are America!”

Hughes used this poem to share the narrative of the enslaved individuals from our country's history and remind his audience of their dreams. He did this to show his audience that there is still a lot to be done to reach these original dreams. He wrote, “If the fight is not yet won, don’t be weary, soldier!” This poem was written in a time when the U.S. was fighting against fascism and for the freedom of others abroad. It was and is a gentle and beautiful reminder that the fight at home is also incomplete. This poem addressed the original goal of the lecture series which was to find “constructive way out in building human relations,” which for Hughes meant ensuring that human relations include equality for African Americans.

-Maddy Starling (UD Summer Scholar 2021)

Program for “The Periclean Club Presents Langston Hughes,” Birmingham, Alabama, February 16, 1945, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware

At the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, The Periclean Club presented Langston Hughes. The program shows that while Hughes was the guest artist, the event equally featured choirs, essay contest winners, spiritual readings, and invocations. The event seemed to be closer to a late-night Baptist service that featured Langston Hughes. According to the program, Hughes performed a reading titled “I, Too, Sing America,” a title based on his most famous poem “I, Too.”

While “I, Too” was originally published in 1926, it is a timeless piece of poetry that is constantly being reread and re-adapted, even today. Most recently, the poem has been shared and read in correlation with the Black Lives Matter Movement.

In 1945, the poem would have spoken to racial inequities in the United States Armed Forces and the Jim Crow South. “I, Too” can be applied to this conversation as it tells the story of the “darker brother” who knows that he will one day having a seat at America’s table. At the time Hughes presented this poem to the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, having a seat at the table would have included meeting the goals of the Double V Campaign. It would have meant embracing Black soldiers on their return home, desegregating the military, and providing equal access to housing and jobs.

This program also speaks to the complexities of the Double V Campaign. The campaign was about promoting patriotism in the fight abroad but also critiquing America’s flaws in its democracy. This complexity can be seen in the fact that at this event both the American national anthem, “The Star Spangled Banner” and the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice” were performed. The performance showed how patriotism and the fight for equality could be intertwined.

The venue for this event also had significance in the fight for racial justice. Eighteen years after this event, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was bombed by white supremacists, which led to the death of four girls. Given that history, it is poignant to know that Hughes interacted with members of the congregation and gave a message of racial equality through the poem “I, Too.” Hughes responded to the bombing with his poem “Birmingham Sunday.”

-Maddy Starling (UD Summer Scholar 2021)

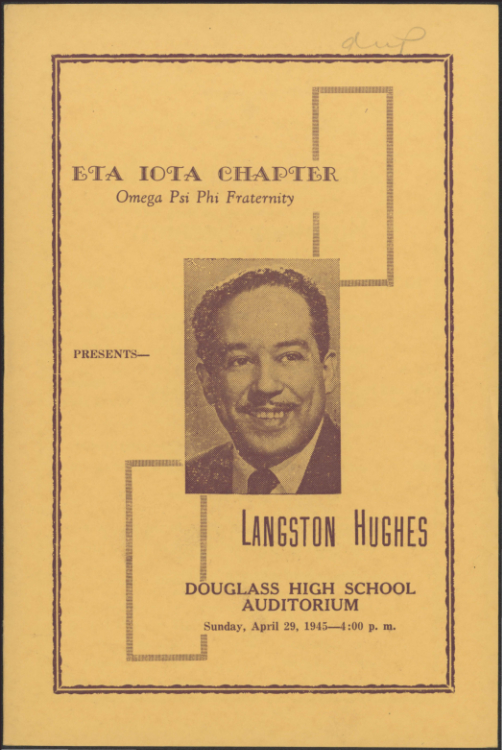

Program for “Omega Psi Phi Fraternity Presents Langston Hughes,” presented by Eta Iota Chapter of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, April 29, 1945, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware

Ten days before V-Day, the day that marked the end of World War II and the victory of the Allied Forces, Langston Hughes was presenting at Douglass High School in Oklahoma City. While the end of the war was near, Hughes still had his eyes on the prize of a double victory that included equality for all in the United States after defeating fascism abroad.

Hughes presented three pieces at this event which included a musical rendition of his poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (performed by Miss Henrietta Beasley and set to the music of Margaret Bonds and Howard Swanson), a lecture on “Color Around the World,” and his song “Freedom Road” (performed by Mr. Clarence Griffin). “Freedom Road” was a song Hughes wrote and Emerson Harper composed to directly address the mantra of the Double V Campaign--freedom and victory both abroad and at home. The song tackled the idea of defeating Hitler and the Nazis while also bringing Black and white soldiers together. The song featured clear patriotic tones by a narrator eager to fight in World War II. However, both Hughes and the singer John White received attacks because of this song and were labeled as communists and “anti-America.” The critiques of this song were not targeting the anti-Nazi and anti-fascism language, but instead the song’s subtle criticisms of America’s own inequalities.

The Writers’ War Board was a United States propaganda organization during World War II. This government agency published work from different American writers to help the efforts to win the war. Hughes wrote in a letter to Katherine Seymour, a member of the Writers’ War Board, about “Freedom Road,” telling her that he had been “able to give a little thought to the problems of the unity at home—victory abroad broadcasts” (quoted in Rampersad 254). He continued to say that radio has “insistently censored out any real dramatic approach to the actual problems of the Negro people.” He remarked that his song “Freedom Road” has been the victim of this censorship as well.

Hughes still performed this song after these criticisms, showing that he was willing to risk his reputation and career by fighting for the Double V Campaign. Ten days before the end of the war, Hughes continued to make a compelling case through his art against the hypocrisy of the United States fighting a war against inequalities and fascism, while its own democracy did not fully encompass every U.S. citizen.

-Maddy Starling (UD Summer Scholar 2021)

Conclusion

There were some victories that came out of the Double V Campaign. On July 26, 1948, President Tuman issued Executive Order 9981, officially desegregating the military on the basis of race, religion, or nationality. The desegregation of the military was an aim of the Double V Campaign. The campaign also created a platform and momentum for the Civil Rights Movement. It broadened the scope of African American issues in the United States, making housing and job equity and segregation core issues. Langston Hughes’ voice added class, credibility, and art to the Double V Campaign. His unwavering commitment to this campaign cannot be ignored when looking at the impact of this movement on African American history.