Langston Hughes had the Midas touch. He left a lasting impact within many areas of the arts—whether it be poetry, lyrics, prose, or librettos. When it came to theatrical or lyrical work, Hughes collaborated with many composers who were, according to scholar Leslie Catherine Sanders, “attracted to his simple, yet elegant lyricism” (594). Hughes’ love for the theatre, fostered by his mother, began in childhood and never wavered. Throughout his autobiography, The Big Sea, Hughes mentions outings to the theatre as a favorite pastime. Moreover, Hughes not only enjoyed the theatre as a spectator but as a writer. Throughout the Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Hughes’ range of theatrical writing is demonstrated through playbills, advertising fliers, and reviews. From cantatas to operas to ballads to gospel plays, Hughes touched them all. In the 1960s, the last decade of Hughes’ life, some of his earlier theatrical works, such as Street Scene, continued to be performed, but he also created a number of new works for stage. He continued to collaborate with composer Margaret Bonds on works such as The Ballad of the Brown King, documented the civil rights movement in Jericho-Jim Crow, and debuted one of his signature contributions to the theater: the gospel play, documented here in ephemera for Tambourines to Glory and The Prodigal Son. These and other gospel plays were, according to Sanders, Hughes’s “most important dramatic works” (4). The theater, much like the rest of Hughes’ oeuvre, illuminated the voices of Black America culturally, politically, and religiously.

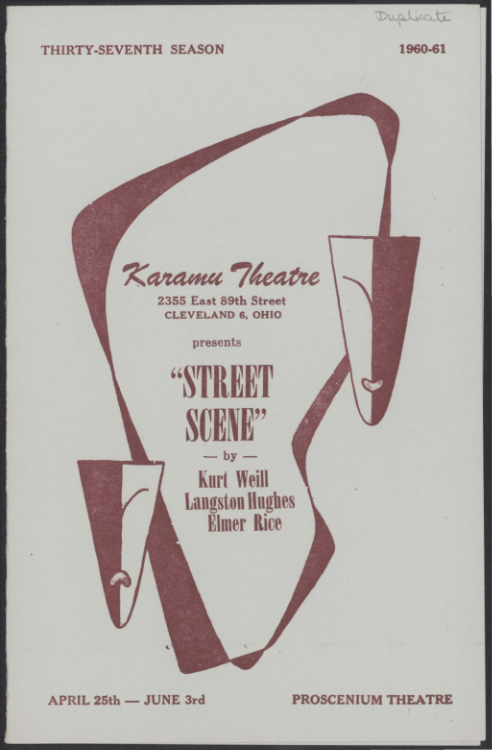

Playbill for Karamu Theatre’s production of Street Scene, Cleveland, Ohio, 1960-1961, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Street Scene is an opera with lyrics by Langston Hughes and music by Kurt Weill. Elmer Rice originally wrote Street Scene as a play in 1926, which won the Pulitzer Prize for drama. The opera was written twenty years later in 1946 and debuted in Philadelphia. The opera version of Street Scene is set in 1946 on the East Side of Manhattan, taking place over twenty-four hours, and centers the residents of a single tenement building. As scholar Leslie Catherine Sanders notes, Hughes’ involvement in Street Scene was notable because African American lyricists were rarely asked to collaborate on plays or musicals about white characters. When it came to picking a collaborator to write the lyrics, Weill looked for someone who could translate “everyday language” into poetry, and he admired Hughes’s musical sensibility. “They wanted someone who understood the problem of the common people,” Hughes remarked.

The original opera ran for 148 performances. While Hughes was alive, Street Scene was revived numerous times and optioned as a film--one of Hughes’ only lucrative ventures in theater. Since 1947, Street Scene has been performed in a number of theaters around the United States and, more recently, in the United Kingdom, with the most recent performance recorded and broadcast in April 2020.

The image above is of the Street Scene playbill from Karamu Theatre in Cleveland, Ohio in 1961. The Karamu Theatre was founded by Russell and Rowena Woodham Jelliffe in 1915 as a common ground in which people of all backgrounds could come together through art. In 1917, the first play was produced at the theatre, then called the Playhouse Settlement. In the 1920s, it quickly became a magnet for African American artists of the time: dancers, actors, and writers all found a place at the Playhouse Settlement. The theatre became an active contributor to the Harlem Renaissance and was a frequent venue for Hughes to develop or stage his work. The Playhouse Settlement was renamed in 1941 as Karamu House. In Swahili, Karamu means “a place of joyful gathering.” The theater is among the oldest African American theaters in the country and is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. According to the playbill, Street Scene was slated to run April 25th through June 3rd of the 1960-1961 season, fourteen years after the opera's creation and debut.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

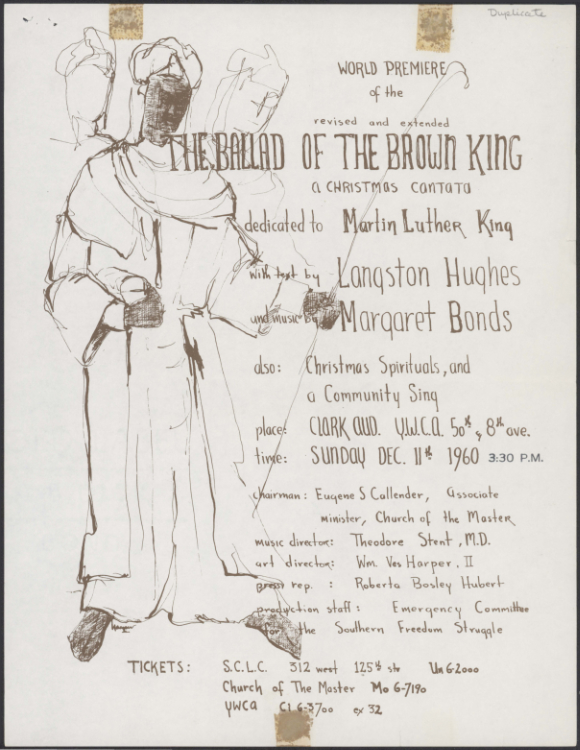

Production flier, The Ballad of the Brown King, Clark Auditorium, YWCA, New York City, New York, December 11, 1960, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

A cantata is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, several movements, and a choir. The term originated from seventeenth-century Italy and is written for special occasions such as Christmas. The Ballad of the Brown King, advertised in this flier, was written by Langston Hughes with music by composer Margaret Bonds. Bonds and Hughes met in 1936 and remained lifelong friends until Hughes' death in 1967. The Ballad of the Brown King, written and first performed in 1954, is one of several works Bonds composed using Hughes' poetry.

As this flier indicates, the world premiere of a revised and extended version of The Ballad of the Brown King would be dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr. The Ballad tells the nativity story with emphasis on King Balthazar. The brown king is meant to represent and pay homage to African American culture. This performance was scheduled for 11 December 1960, six years after the first performance of the piece, and included a full orchestra and additional text by Hughes. The Ballad of the Brown King was televised by CBS in December, 1960.

Bonds’ decision to dedicate the revised and extended version of The Ballad of the Brown King to Martin Luther King, Jr. reflected the changing political context of the cantata’s ongoing performance. The performance was held at the YWCA’s Clark Auditorium in New York as a benefit for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC was founded in Alabama in 1957, and King was elected as its first president. The beginnings of the SCLC can be traced back to the Montgomery Bus Boycott which began in December 1955, a year after the debut of The Ballad of the Brown King. This 1960 premiere of the revised and extended version was produced by the Emergency Committee for the Southern Freedom Struggle and chaired by Eugene S. Callender, associate minister of the Church of the Master. Callender was a civil rights activist and pastor who was the first African American to study at Westminster Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania, the first Black ordained minister in the Christian Reformed Church in North America (CRCNA), and the deputy administrator for the New York City Housing and Development Administration. Like Hughes, Callender spent most of his life in Harlem.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

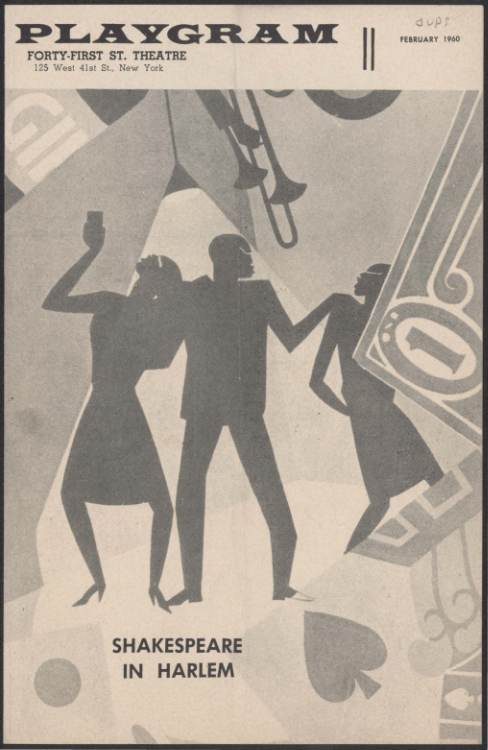

Playgram for Forty-first St. Theatre’s production of Shakespeare in Harlem, New York, New York, February 1960, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Shakespeare in Harlem was originally a volume of poems by Langston Hughes published by Alfred Knopf in February 1942. Hughes’s biographer, Arnold Rampersad, described the volume as eschewing the radicalism of Hughes’ 1930s poetry and revisiting elements of his 1920s work such as the blues (12). White playwright Robert Glenn brought Shakespeare in Harlem to the stage in 1960 based on Hughes’s volume of poems, with Margaret Bonds, Hughes’ collaborator, composing the musical score. Shakespeare in Harlem, documented in this playgram, ran for only thirty-two performances on Broadway. The illustration on the playgram is reminiscent of the roaring twenties, the Harlem Renaissance, and the Jazz Age, represented by flappers, a bottle of gin, spades, money, and a hand playing the trombone. The illustration is from “Prodigal Son,” a painting by Aaron Douglas, leading visual artist of the Harlem Renaissance as well as the first Black artist to create a distinctly modernist aesthetic connecting contemporary African Americans to their African heritage. Douglas provided art for many literary works, including Hughes’ Not Without Laughter and James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombones.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

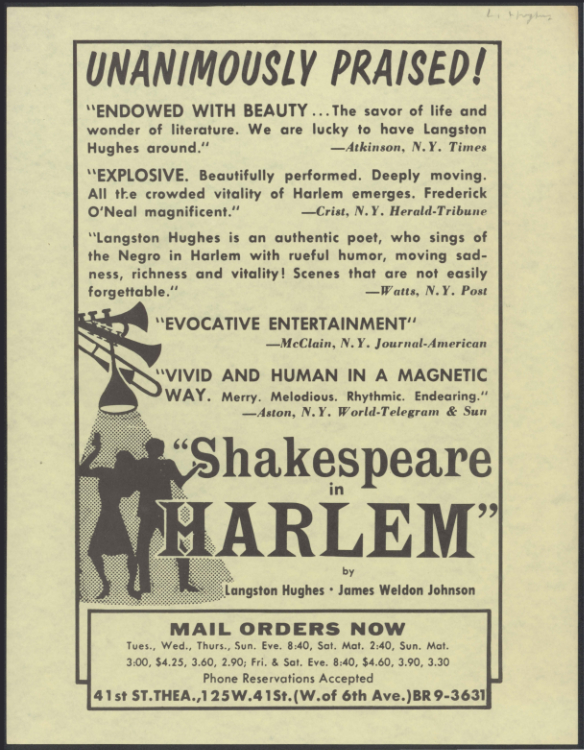

Production flier for Forty-first St. Theatre’s production of Shakespeare in Harlem, New York, New York, February 1960, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

This flier advertises Shakespeare in Harlem with blurbs from reviews of the play from several New York newspapers. The bottom of the flier states, “Mail Orders Now” with ticket prices to view the play at the Forty-first Theater in New York. Next to Hughes’ name at the bottom of the flier is the name of civil rights activist and Harlem Renaissance writer James Weldon Johnson. He was a leader of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in the 1910s and 1920s. Johnson’s book turned short play, God’s Trombones, a folktale of the biblical Old Testament, was playing at the Forty-first St. Theater alongside Hughes’ Shakespeare in Harlem, twenty-two years after Johnson’s death in 1938.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

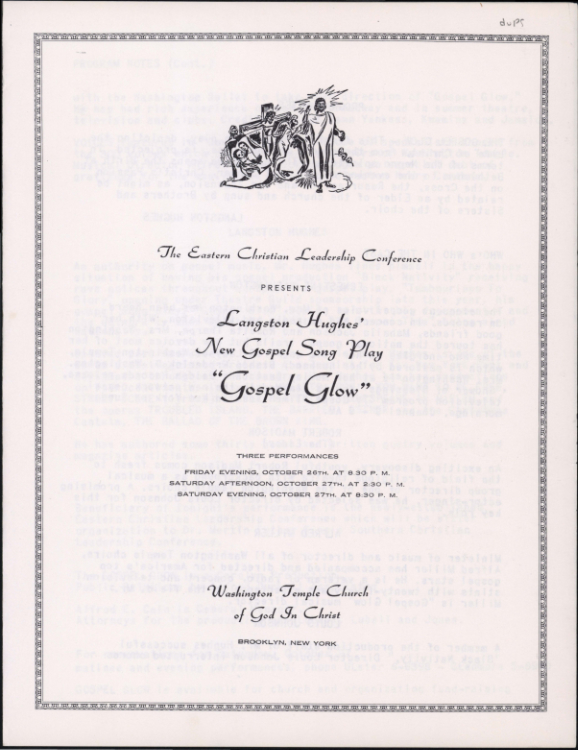

Flier for the Eastern Christian Leadership Conference production of “Langston Hughes’ New Gospel Song Play Gospel Glow,” Washington Temple Church of God in Christ, Brooklyn, New York, October 26-27, 1962, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Langston Hughes’ gospel play, Gospel Glow, was a passion play--a genre that presents a dramatic representation of the passion of Jesus Christ. Hughes notes that this is the first Negro passion play, “depicting the life of Christ, from the cradle to the cross.” Hughes made use of African American spirituals for this production, with the singers comprising the five choirs of Washington Temple-- a total of 300 singers. Louis Johnson, who was on the production staff for Hughes’ Black Nativity, was the director of Gospel Glow. This production was presented by the Eastern Christian Leadership Conference (ECLC), a newly-established sister organization of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Gospel Glow was not the first of Hughes’s theatrical productions to benefit the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; a 1960 production of The Ballad of the Brown King also raised money to benefit this civil rights organization. The performance was slated to run from October 26-27, 1962, at the Washington Temple Church of God in Christ in Brooklyn, New York.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

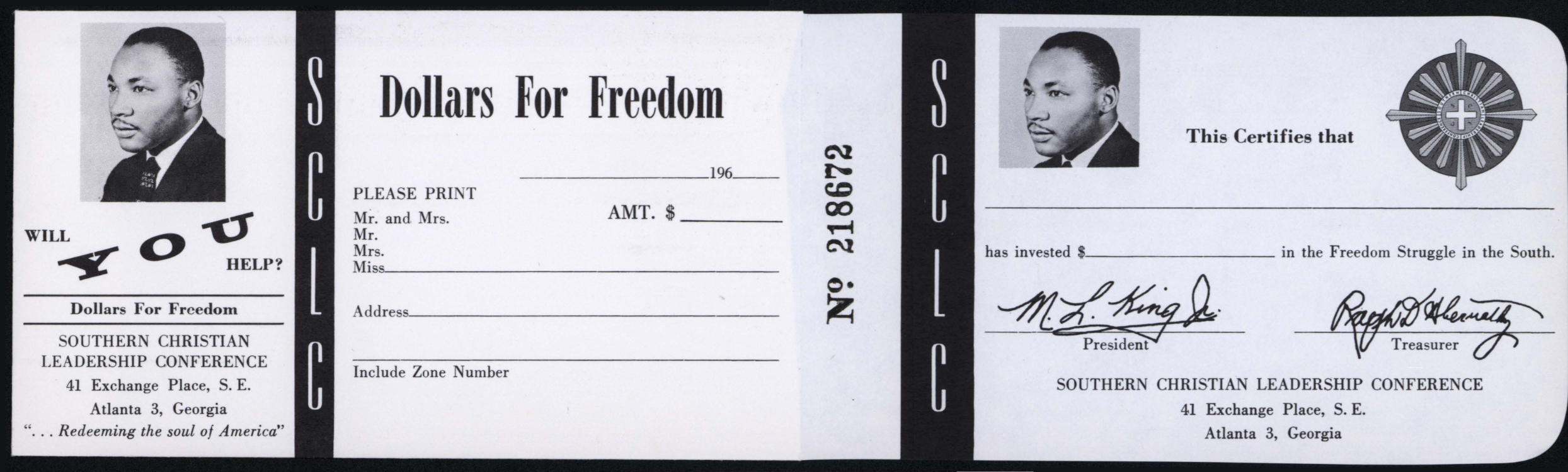

Donation slip for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's “Dollars for Freedom” campaign, Atlanta Georgia, October 26-27, 1962, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library. Produced in Atlanta, these slips were also used in Washington D.C. and Brooklyn, New York.

Enclosed in the Gospel Glow program is a Dollars for Freedom donation slip and envelope created by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, featuring a photograph of King. This production of Gospel Glow solicited donations from audience members to support civil rights organizing in the South. The left half of the donation slip was to be filled out and placed in the envelope with the amount being donated while the right half of the donation slip could be kept as a detachable keepsake card with King’s facsimile signature certifying the individual’s donation to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

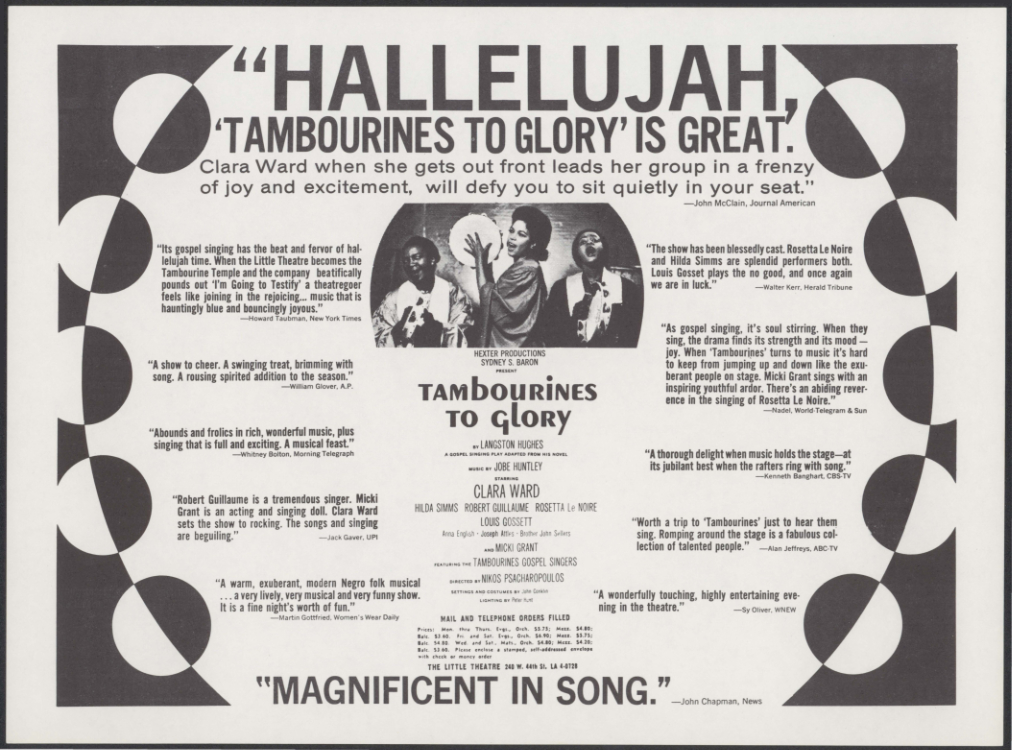

Flier for Little Theatre’s production of Tambourines to Glory, New York, New York, November 1963, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Tambourines to Glory was a gospel play by Langston Hughes written in 1956 and published as a novel in 1958. The music was written by Harlem composer Jobe Huntley and featured gospel singer Clara Ward as one of the lead performers in the play. Tambourines to Glory is about two female street preachers who open a storefront church in Harlem. Scholar Leslie Catherine Sanders describes the play as “simultaneously comical, satirical, and critical of certain religious practices” while also celebrating “the power of Black religious musical expression and the faith it supports” (280). Hughes’ invention of the gospel play is notable given his ambivalence about organized religion. As biographer Wallace Best argues, Hughes’s work was permeated by “religious themes, discourses, theological frameworks, and spiritual cadences” in spite of that ambivalence (29-31). Arnold Rampersad adds that Hughes “knew that religion had been crucial to black survival” and “associated it above all with an art that absorbed but also transcended organized religion” (22). In the 1950s, when Tambourines to Glory was written, Hughes was still under fire for his 1932 poem "Goodbye, Christ," a focus of interrogation when he was questioned about his Communist ties by Joseph McCarthy's Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. But Hughes’s past critiques of organized Christianity did not negate his deep interest in Black religious practices, and his invention of the gospel play is one example of that abiding interest.

This image is of an advertising flier for the gospel play with blurbs from ABC-TV, New York Times, Women’s Wear Daily, CBS-TV, and Herald Tribune, among others, as well as production information and ticket prices. The image on the flier is likely of the three lead gospel singers: Rosetta Le Noire, Hilda Simms, and Clara Ward. The play opened on Broadway at the Little Theatre in 1963 and ran for a few weeks in November.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

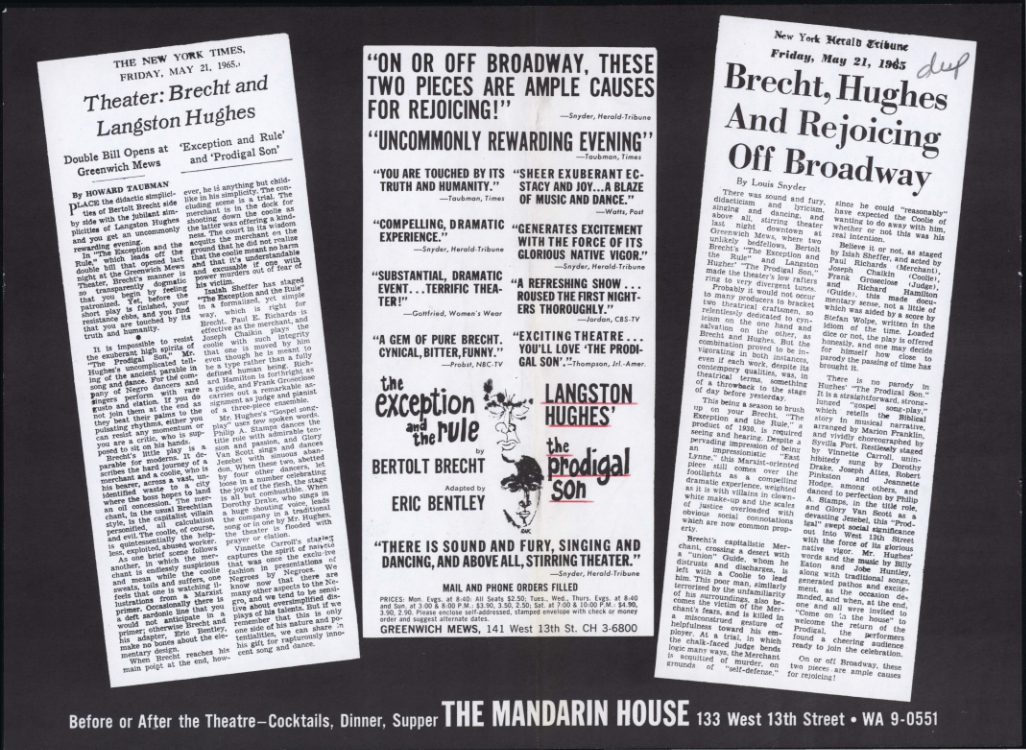

Newspaper article clippings for Langston Hughes’ The Prodigal Son and Bertolt Brecht’s The Exception and the Rule, Greenwich Mews Theatre, New York, New York, September 3, 1965, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

The Prodigal Son is a gospel play Hughes quickly finished writing in December 1961 after writing the musical play Black Nativity. In 1965, The Prodigal Son, in a double billing with Bertolt Brecht’s The Exception and The Rule, opened at the Greenwich Mews Theatre in New York, garnering positive reviews and enjoying robust attendance. The Greenwich Mews Theatre operated out of a 200-seat theater in the Village Presbyterian Church, and was one of just a few theaters producing shows with integrated casts. The venue’s manager was Stella Holt from 1952 through 1967. She welcomed production of works by people of color and produced works by Langston Hughes and many other Black writers.

The first image is a collage of newspaper clippings, one of which is the New York Times review by Howard Taubman in which he describes both plays. He describes Brecht’s “little play” as “a parable for Moderns. It describes the hard journey of a merchant and a coolie who is his bearer, across a vast unidentified waste to a city where the boss hopes to land an oil concession.” On Hughes, Taubman writes, “It is impossible to resist the exuberant high spirits of ‘The Prodigal Son,’ Mr. Hughes’ uncomplicated telling of the ancient parable in song and dance.”

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

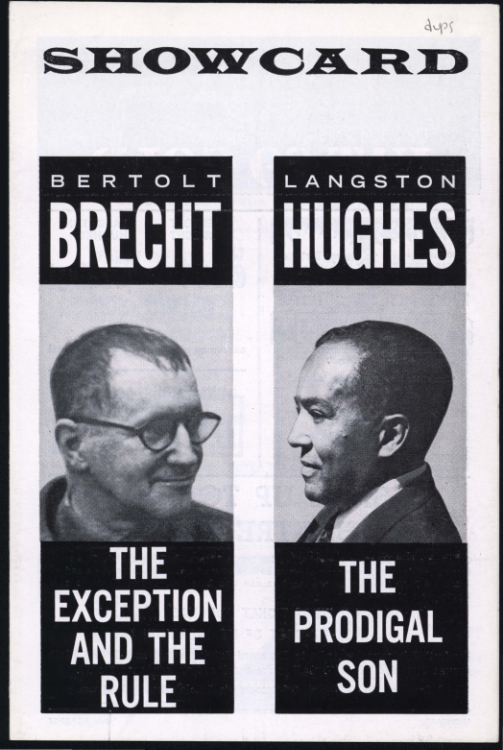

Production showcard for Greenwich Mews Theatre’s productions of Langston Hughes’ The Prodigal Son and Bertolt Brecht’s The Exception and the Rule, New York, New York, September 3, 1965, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Bertolt Brecht was a German playwright and poet. He is considered to be one of the most prominent figures of twentieth-century theater. Like Hughes, Brecht collaborated with Kurt Weill on an opera. In 1924, Brecht and Weill wrote The Threepenny Beggar, which they adapted from John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera. Hughes met Brecht in 1937 when he traveled to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War for the Baltimore Afro-American. During this time, Hughes met many leftist writers, though he and Brecht never appeared to have collaborated with each other in the theater. Brecht died in 1956, nine years before the double bill of The Prodigal Son and The Exception and The Rule at the Greenwich Mews Theatre. While The Exception and The Rule was a restaging of a relatively early piece (1930) from Brecht’s oeuvre, The Prodigal Son was a recent work by Hughes, and thus the Marxist themes in Hughes’s early work, which would have resonated with Brecht’s play, are absent. This is the last play of Hughes to debut before his death two years later.

-Britney Henry, Special Collections intern and PhD student in English

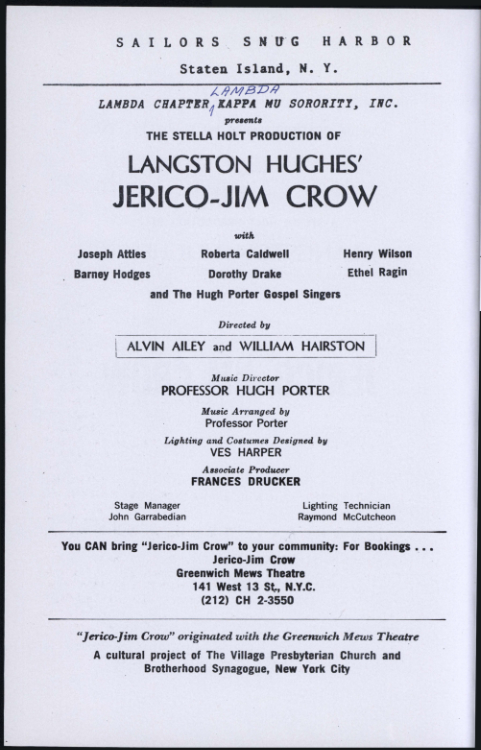

Production flier for the Stella Holt production of Langston Hughes’ Jerico Jim Crow, Staten Island, New York, 1964, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Jerico-Jim Crow, a musical written by Langston Hughes and directed by Alvin Ailey and William Hairston, was a gospel tribute to the civil rights movement, first staged in 1964 at the Greenwich Mews Theatre. It featured a history of African American freedom dreams via traditional songs, performed by the Hugh Porter Gospel Singers, as well as original songs written by Hughes entitled “Freedom Land” and “Such a Little King.” In “Freedom Land,” the singer, Henry Wilson, argued that he had every right to freedom and expressed anger with people who stalled change by suggesting that “tomorrow is another day, let things take their course.” Hughes personified the antagonist “Jim Crow,” portraying him as a racist southerner, a police officer, and a slave trader. The show’s performance in New York City also underscored the fact that the freedom struggle had to take place in the North as well as the South. Hughes used this production to spread awareness and educate. This performance of Jerico-Jim Crow on Staten Island was sponsored by the Lambda Chapter of Lambda Kappa Mu, a sorority for African American women. This detail is important as it shows how African American organizations supported and helped disseminate Hughes’ work. He used this play to educate. Not only did this production highlight Hughes' strengths as a writer, but it also revealed his show of support for those on the front lines of the civil rights movement.

-Jocelyn Santana (Class of 2021)