The 1920s had been Langston Hughes’ breakout decade: the publication of his signature poem, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” in The Crisis in 1921, followed by his acclaimed poetry collection, The Weary Blues, and his manifesto, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” both appearing in 1926. Within a few years, as the Great Depression roiled the United States, Hughes became increasingly radicalized by the racial and economic injustices he witnessed in America and by the political possibilities offered by communism and the example of the Soviet Union. His poetry and plays of the 1930s reflected his commitments to workers’ rights and racial equality—from his verse play “Scottsboro Limited” to the critique of capitalism in his poem “Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria.” As he traveled, especially in his poetry tours of the U.S. South, he experimented with ways to broaden the reach of Black literature by printing cheap editions of his work affordable for a mass audience. In 1932-33, he traveled extensively in the Soviet Union. He planned to return to the Soviet Union in 1937, but instead went to Spain as a correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American to write about the experiences of African American soldiers who volunteered to fight for the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War—a fight many Black Americans saw as a second chance to oppose the wave of fascism in Europe that had led to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. When Hughes returned home from Spain in 1938, he launched a speaking tour on which he brought his internationalist vision to U.S. audiences with a talk variously called “A Negro Poet Looks at the World” or “A Poet Looks at a Troubled World.”

Brochure for Edutravel, Inc., “Langston Hughes, Poet-Playwright Directs a Survey [of] National Minorities in Europe and the Soviet Union,” circa 1937, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

This brochure advertises Langston Hughes’ planned trip to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1937, although this trip never actually happened. Hughes cancelled it in order to act as a reporter in Spain during the civil war--a fight between the left-leaning Second Spanish Republic, supported by forces from the Soviet Union and the International Brigades, and the insurrectionist Nationalists, supported by fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. Despite the cancellation, this brochure reveals much about Hughes’ continued support for the Soviet Union and its leftist political ideology. The brochure also reveals the reasons Hughes was in favor of the Soviet brand of socialism. Namely, Hughes saw how much better the minority populations of these countries were treated as compared to the United States and other capitalist nations. Though Hughes certainly had his radical and revolutionary moments, his enthusiasm for certain aspects of leftist ideology was in a constant state of flux throughout his life. However, his passion for racial equality, and how it could be achieved through socialist principles, never waned.

Langston Hughes was not always so explicitly political. In his early poems he dreamed of one day living in an equal America, but he never proposed how the country might get there. Hughes was deeply affected, however, by the infamous Scottsboro trials of 1932, in which nine Black teenagers were wrongfully accused and convicted of raping two white women--and were defended by the Communist Party of the United States. In his poem on the case, entitled simply “Scottsboro,” published in Opportunity, Hughes first makes reference to the Soviet Union in the line, “Lenin with the flag blood red.” The Soviet Union had clearly ignited Hughes’ interest. His trip to the country in the summer of 1932 would make him a truly radical poet.

Hughes embarked on this trip with twenty-one other young Black American artists in order to film a Soviet propaganda film on the evils of American racism called “Black and White.” This band of travelers had trouble seeing eye to eye, some being staunch communists and some refusing to align themselves with any leftist ideology at all. Hughes, however, showed no such reticence. Hughes’ biographer Arnold Rampersad noted, “Hughes himself had oscillated between radical fervor and compliant sentimentality, between worship of the masses and an attachment to luxurious patronage, between radical socialist discipline and an almost aimless anarchy of consciousness. Now he was in the motherland of world revolution, where political indecisiveness has no place” (244).

“The system under which the successful live – left, or right – capitalist or communist – did not seem to make much a difference to that group of people.” - Langston Hughes

Hughes combined a commitment to revolutionary causes with his characteristic pragmatism, but he believed that communism provided a potential answer to racial issues: “I have seen dark races exploited unmercifully the world over. And now . . . I have at last seen a country where the dark people are given every opportunity” (quoted in Rampersad 264-65).

In this tour planned for the summer of 1937, Hughes was to lead an interracial group of travelers in witnessing the opportunities given to “national minorities” in the Soviet republics. Ultimately, however, Hughes spent the summer reporting on African Americans who had traveled to Spain and joined the Soviet-led International Brigades in their fight against fascism.

-Nicholas Carlino (Class of 2021)

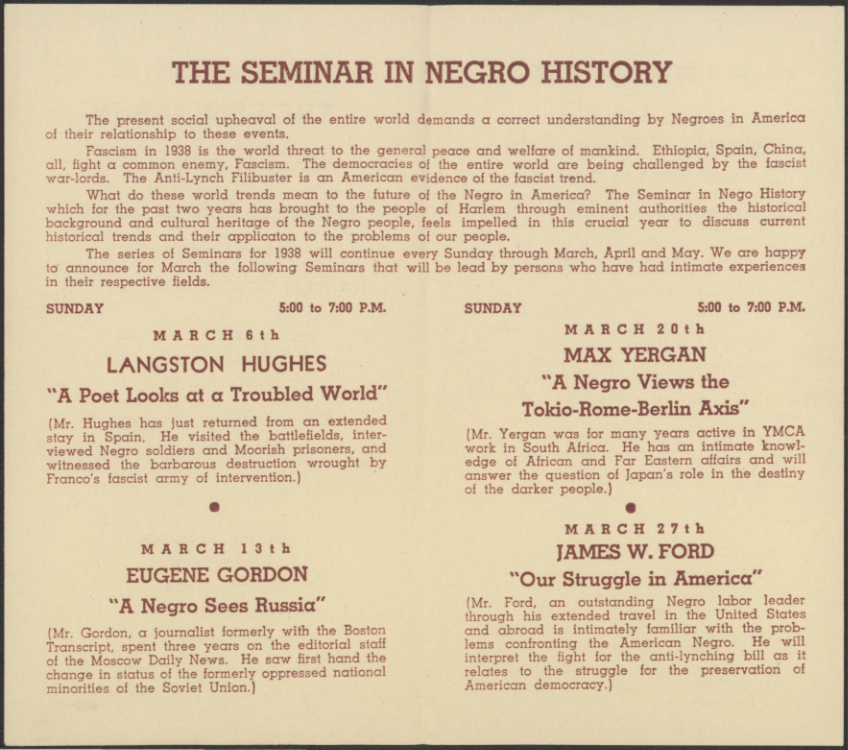

Program for Langston Hughes' "A Poet Looks at a Troubled World" lecture at The Seminar in Negro History event, Harlem Community Center, Solidarity Br. 691 of the International Workers Order, New York, March 6, 1938, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

When Langston Hughes returned to the United States after covering the Spanish Civil War in 1937, he started on a tour around the country that was sponsored by leftist and racial equality groups, most notably and consistently the International Workers Order (IWO) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This tour was titled “A Negro Poet Looks at the World.” Hughes likely shared his thoughts on global issues of racial equality and the threat of fascism. A flier for one of his talks on this tour stated that Hughes “looks at the world today that is full of alarms, wars, and threats to world peace and democracy.” For “The Seminar in Negro History,” pictured here, Hughes gave a talk with a slightly different title: ”A Poet Looks at a Troubled World.” He discussed “the barbarous destruction wrought by Franco’s fascist army.” Here was Hughes’ opportunity to discuss what he had witnessed in Spain and share his perspective on fascism.

This speaking event connects to Hughes' 1937 poem “Madrid,” with the lines “In the darkness of her broken clocks / Madrid cries NO! / In the timeless midnight of the Fascist guns, / Madrid cries NO! /To all the killers of man’s dreams, / Madrid cries NO! / To break that NO apart / Will be to break the human heart.” In this poem, Hughes illustrates how the Nationalists taking over Madrid had put out a light of hope for the Republicans’ ideals of freedom, democracy, and equality. World War II started just months after the end of the Spanish Civil War, with the German and Italian forces joining sides again to try to spread far-right politics to the rest of the world, fighting against the Soviet Union and other Allied forces that acted to stop the spread of fascism. Many historians consider the Spanish Civil War a precursor to World War II. The Nationalists’ victory in Spain turned the tide in favor of fascism in Europe, adding to its power in countries such as Italy under Mussolini and Germany under Hitler.

-Alex Carey (Class of 2021)

Flier, Langston Hughes’ “First Appearance in Chicago,” March 29, 1938, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

A single-page advertisement for an appearance by Hughes following a tour in Spain, this flier was printed on a single-sided sheet of paper. It is one of several pieces of ephemera from 1938, when Hughes embarked on a speaking tour sponsored by the International Workers Order (IWO). Each flier prominently advertises Hughes’ recent return from Europe, especially Spain, where he had covered the Spanish Civil War for the Black press, an experience he chronicles in his second memoir, I Wonder as I Wander.

For this event in Chicago, a number of “leading citizens” would be present to honor Hughes, as shown in the list on the right of the flier. They included representatives of the Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee (PWOC), Chicago Urban League, National Negro Congress, and several leftist or African American newspapers. Other organizations involved were the Metropolitan Community Church, which hosted the event, and the Frederick Douglass Lodge of the IWO, which sponsored it. Of note on the list of “leading citizens” is the presence of Arna Bontemps, a fellow writer and close friend of Hughes. Bontemps appears quite frequently throughout the ephemera, often co-performing with Hughes. Nevertheless, Bontemps was not as highly regarded or famous as Hughes, despite being his peer. Although named for Hughes, the ephemera collection highlights precisely this sort of individual, who traveled in the same circuits as Hughes but may not have been as popular or well-known.

-Hayden Troy (Class of 2021)

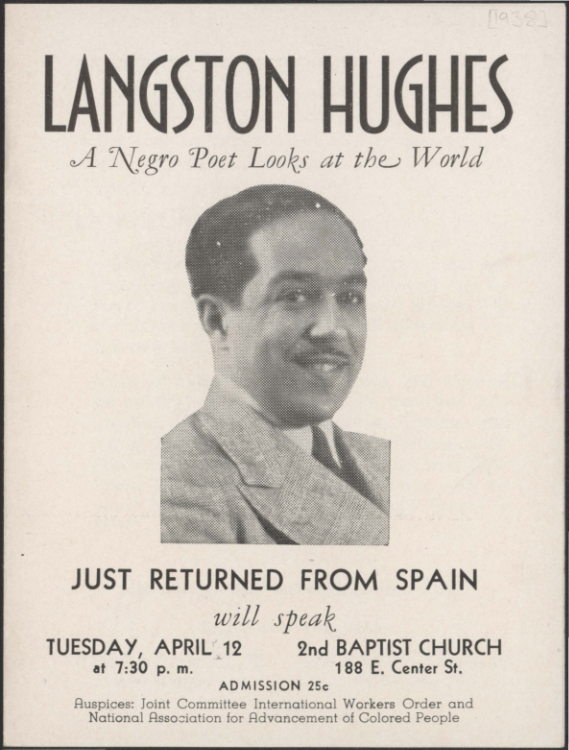

Flier, Langston Hughes: “A Negro Poet Looks at the World,” appearance at 2nd Baptist Church, Akron, Ohio, April 12, 1938, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

Hughes’ travels to the USSR in 1932-1933 were highly influential in the development of his radicalism. His distance from the United States gave him the room necessary to evaluate American culture from the lens of a foreigner. This new sense of objectivity allowed Hughes to assess and recognize how irrefutably entrenched the tradition of capitalism was in America, even in its church system. However, despite the unabashed criticism of religious authority present in Hughes’ works like the poem “Goodbye Christ,” Hughes was still present in houses of worship across America as a frequent and treasured speaker.

How does one reconcile the poet’s subversive secular writings with his presence in the church?

On April 12, 1938, Langston Hughes was the featured presenter at a “A Negro Poet Looks at the World” event held at the Second Baptist Church in Akron, Ohio. As evident in the program, Hughes’ engagement was co-sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and by the International Workers Order, a fraternal order associated with the Communist Party that received his leftist attitudes with open arms. This event represents an apparent contradiction between Hughes’ “blasphemous” poems of the early thirties and his consistent engagement with the church. However, events like “A Negro Poet Looks at the World” captured the interests of differing Christian communities who supported Hughes for several reasons. The first stems from Hughes’ lifelong insistence that he was not in fact, an “atheist.” This repeated proclamation, viewed in conjunction with his frequent participation in church services or his readings in church venues, casts a different light on the poet than the one adopted by his critics: Hughes was not a sacrilegious man. Rather, he could be characterized as an individual deeply appreciative of the church’s role in community engagement, especially its importance within Black communities, while also recognizing the imperfections of the institution.

Ephemera such as this program reveal that Hughes had a complex and often mutually beneficial relationship with the church. Christians who did not disavow the artist recognized Hughes’ seemingly inflammatory works to be valid assessments of capital-driven religious institutions. Hughes’ value as a celebrated artist and a speaker also outweighed any controversy attached to his personal ideologies. As observed in the flier, events featuring Hughes’ work provided vital safe spaces for members of the Black community to gather and exchange ideas. This particular engagement makes overtly clear that Hughes blended two critical communities: the political and religious domains.

-Jane GaNun (Class of 2021)

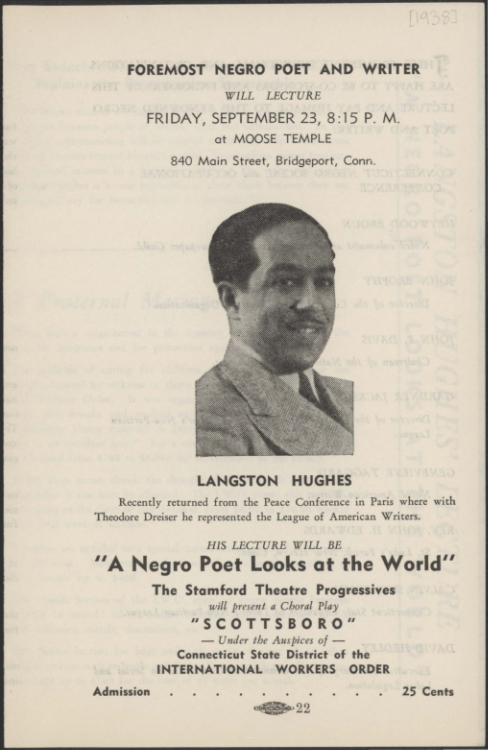

Program for Langston Hughes appearance at Moose Temple, with performance of “Scottsboro,” under the auspices of the Connecticut State District of the International Workers Order, Bridgeport, Connecticut, September 23, 1938, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

The appearance of Langston Hughes at the Moose Temple in Bridgeport, Connecticut on September 23, 1938, was similar to other events that year when Hughes read his poetry for leftist and activist audiences - in this case under the auspices of the International Workers Order. In Bridgeport, Hughes gave his lecture, “A Negro Poet Looks at the World,” and the Stamford Theatre Progressives group staged the choral play “Scottsboro,” which was likely a performance of Hughes’ “Scottsboro Limited,” a “play in verse.”

In the Scottsboro trial, eight Black boys were accused of raping two white women in Alabama in 1931. In his play, Hughes conceptualized the racism of the criminal justice system, injustice and maltreatment of Black Americans, and the struggle of oppressed minorities across time. The play aimed to awaken members of the audiences of different races to work as comrades to “fight the great fight / To put greed and pain / And the color line’s blight / Out of the world / Into time’s old night.”

This program shows that Hughes was not only a writer and artist, but also an important activist. His response to the Scottsboro boys, whom he met in 1932, echoed other moments when he combined his travels and activism during some of the most important decades in history of the nation. In 1927, for example, Hughes took a road trip with Zora Neale Hurston. On that trip, he witnessed a chain gang--a group of prisoners chained together to perform menial or physically challenging work as a form of punishment, such as building roads or repairing buildings. Hughes wrote about the Black men in the chain gang in his poem called “Road Workers.” Hughes’ commentary on Jim Crow laws in the South, racial inequalities, and lynching culture coalesced in one of his most well-known poems, “Let America Be America Again.” Published in the July 1936 issue of Esquire magazine, the poem emphasizes the idea that ‘America’ is only a wish never realized. “I am the people, humble, hungry, mean”: the speaker of the poem stands for all those condemned and oppressed, for whom America “never was.” The poems “Road Workers” and “Let America Be America Again,” and his play, “Scottsboro Limited,” are examples of Hughes’ activist writing.The framing of the Scottsboro boys, and years later, the lynching of Emmett Till, were injustices that heavily impacted Hughes' life and work.

-Emily Bravo Crespo (Class of 2021)

![Brochure for Edutravel, Inc., “Langston Hughes, Poet-Playwright Directs a Survey [of] National Minorities in Europe and the Soviet Union,” circa 1937, Langston Hughes ephemera collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/langston-hughes/wp-content/uploads/sites/241/2021/08/01-edutravel-pp1-2.jpg)