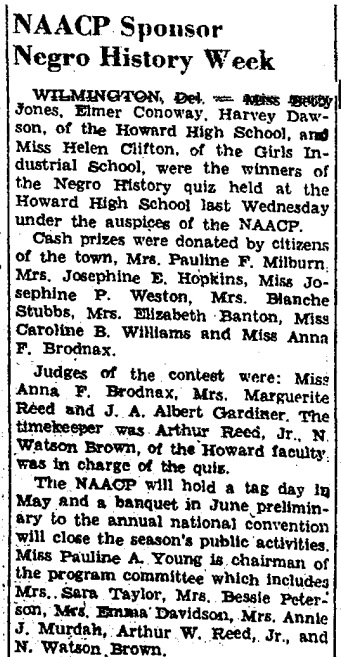

Pauline Young grew up with an acute awareness that Black history and Black achievements had long been overlooked and ignored in the United States. This disregard was even more apparent during her time working at Howard High School, where textbooks used to educate Black students failed to include information about their own people. Young made it her mission to collect as many items related to Black history as possible, from newspaper clippings to magazine articles to photographs to artifacts to ephemera. She took every opportunity to educate others on this history in everyday conversation. She was also dedicated to celebrating these stories of the past in organized events, such as during what was then known as Negro History Week--the predecessor of Black History Month.

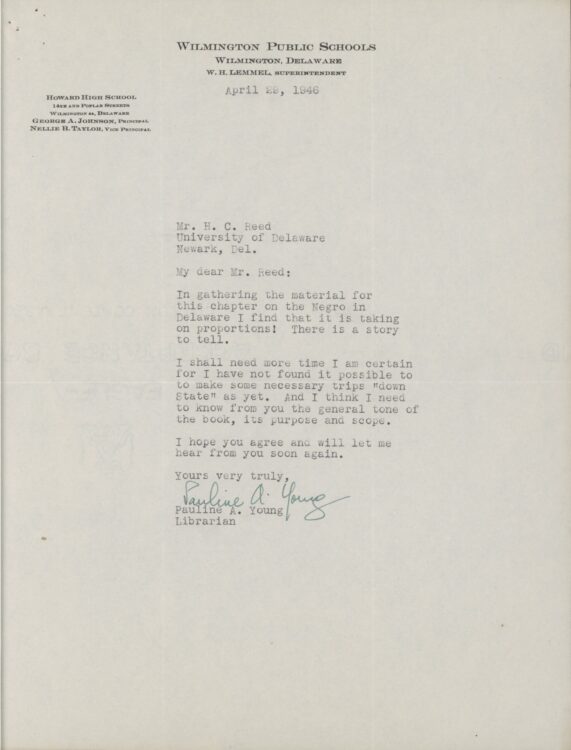

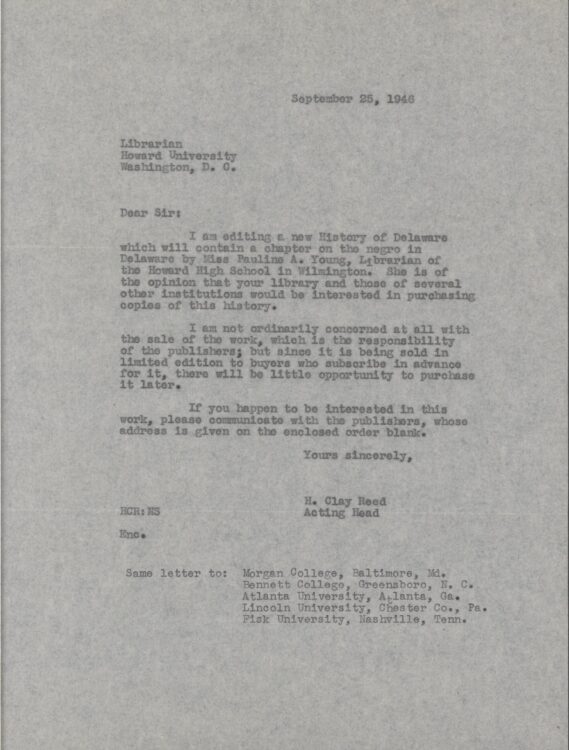

Young had the opportunity to bring this history to a wider audience when she was recruited by historian Henry Clay Reed to write a chapter on Black history for his three-volume work on the history of Delaware, which was published in 1947. With Black history having been dismissed for so many years, this chapter would be the first comprehensive account of Black history for the state. Young threw herself into the project, enthusiastic about the information she uncovered and traveling around the state to learn even more. She encouraged Reed to send word of the chapter’s existence to institutions beyond those in Delaware so that they could benefit from information about this long-overlooked history.

After retiring from Howard High School in 1955, Pauline Young continued her crusade to ensure that younger generations knew their history. She donated some of her collected materials to Howard to make them easily accessible for future high schoolers. She taught Black history to college students at the University of Delaware in the 1980s. She also sold her aunt Alice Dunbar-Nelson’s papers, including letters and manuscripts, to the university so that they could be preserved in the institution's Special Collections department. Her home in Ardencroft, still full of material despite her efforts to distribute items elsewhere, was a repository of Black history in itself, with researchers visiting to consult materials and institutions such as historical societies and the public library calling on Young for her subject expertise.

Toward the end of her life, others recognized Young herself as a living piece of Black history, asking her to speak about the things she’d seen over the course of her life and shine a more personal light on major events. She was honored with several awards. Some organizations even erected plaques recognizing her achievements. In her interviews and acceptance speeches, Young was quick to draw attention to her predecessors, such as her mother and her aunt, as well as activists, artists, and other individuals in the Black community in the hopes that their contributions to society would be recognized as well.