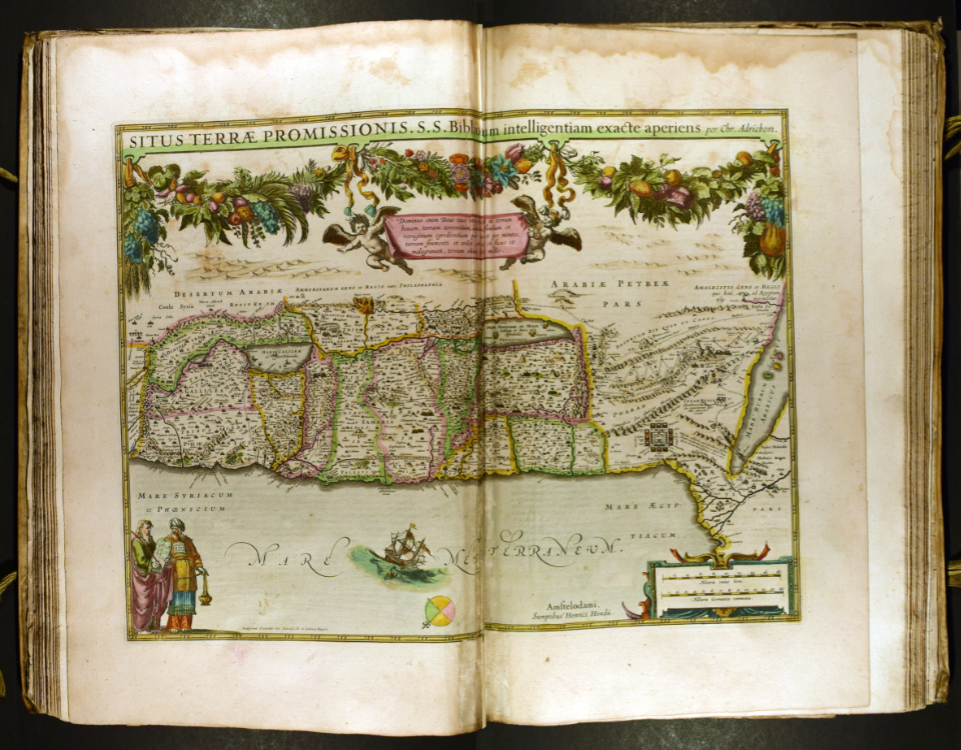

Situs Terrae Promissionis. S.S. Bibliorum intelligentiam exacte aperiens per Chr. Adrichom, in Atlantis Novi, Pars Tertia

Henrik Hondius (1597–1651) and Johannes Janssonius (1588–1644)

Amsterdam, 1638

20.5 x 13 x 3 in. (52.1 x 33 x 7.6 cm)

University of Delaware Special Collections, Folio+ G 1007 .A7 1638

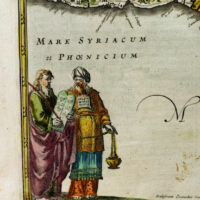

This vibrantly colored map depicts the Mediterranean Sea and the Middle East. Leafy branches adorned with bright flowers and ripe fruits crown the page. Unexpectedly, the top of the map is oriented east instead of north. Why did the mapmakers make this choice? The two figures at the lower left provide several clues. The man at the far left is identifiable as Moses due to the tablets of the Ten Commandments in his hands. To his right is his brother Aaron, who wears a priestly breastplate. The brothers play prominent roles in the Book of Exodus, the details of which appear on this map. Close inspection reveals that it outlines the Israelites’ winding path through the desert and marks significant events that occurred along the way. On the right side, they cross the “Mare Rubrum,” or Red Sea. Higher up on the page, Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai. These elements emphasize the historical and religious significance of this region. This map, which conveys a biblical narrative through a cartographic format, encourages viewers to travel back in time to trace the Exodus story.

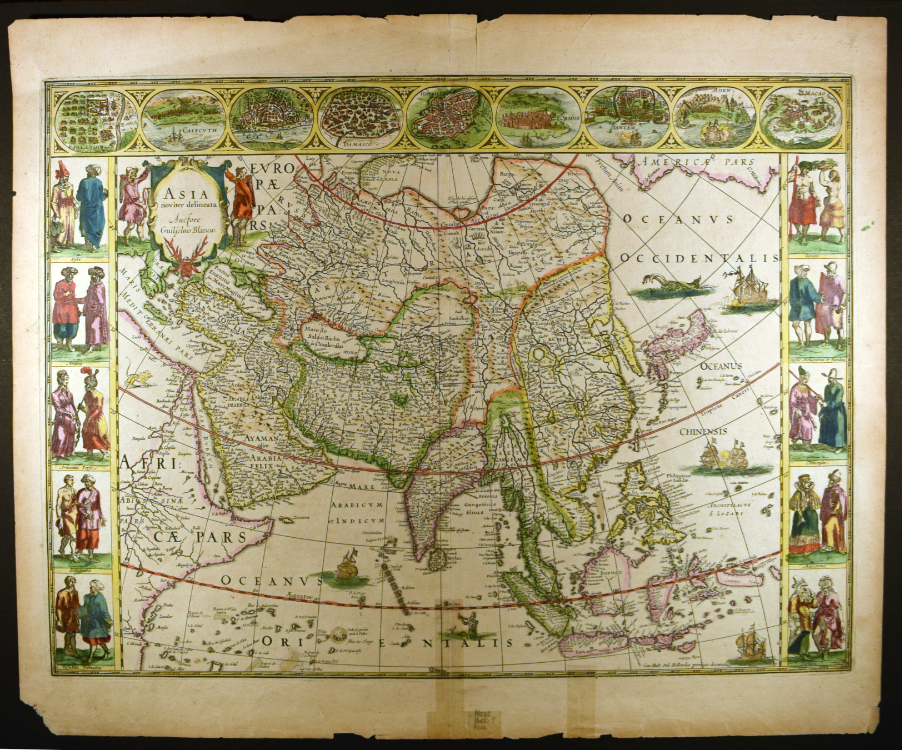

Asia noviter delineata

Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571–1638)

Amsterdam, about 1640

Hand-colored engraving

19.5 x 23.5 in. (49.5 x 59.7 cm)

University of Delaware Special Collections, 01812 gr

Can maps help us think about human difference? For the Dutch cartographer Willem Janszoon Blaeu, who worked for the Dutch East India Company, maps provided an opportunity to represent each continent’s inhabitants in detail. Here, he renders the people of Asia, who he arranges by ethnicity, in pairs along the left and right edges. This orderly arrangement, as well as the accompanying labels, suggests Blaeu’s desire to categorize and classify humankind. He takes the same approach in his maps of Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

Maps can also visualize colonization. The cities depicted along the top row were strategically important to colonizing powers. For example, Macao was a Portuguese colony, and it functioned as a point of arrival for Jesuit missionaries in Asia. Similarly, the port of Bantam was critical to the spice trade. The ships that occupy prominent positions in several of these scenes suggest a European colonial presence. Interestingly, the arrangement of the cities from left to right does not correspond to their geographic locations. Jerusalem occupies the middle of the row, but not the center of the continent. Its placement instead reflects its enduring significance to European Christians.

For additional information about the cities and people depicted in Asia noviter delineata, please see Asia as Defined by Dutch Mapmakers by Zixin Ma.

For additional information on connections between cartography and the European colonization of Asia, please see French and Dutch East India Companies by Mireille Miller.

![[Detail of Moses and Aaron]. Situs Terrae Promissionis. S.S. Bibliorum intelligentiam exacte aperiens per Chr. Adrichom, in Atlantis Novi, Pars Tertia. Amsterdam, 1638.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/multiple-middles/wp-content/uploads/sites/239/2021/05/mercator-promissionis-FolioG1007.A7_1638-DETAIL-MOSES-AARON.jpg)

![[Detail showing the Red Sea and Mount Sinai]. Situs Terrae Promissionis. S.S. Bibliorum intelligentiam exacte aperiens per Chr. Adrichom, in Atlantis Novi, Pars Tertia. Amsterdam, 1638.](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/multiple-middles/wp-content/uploads/sites/239/2021/05/mercator-promissionis-FolioG1007.A7_1638-DETAIL-MARE-RUBRUM.jpg)