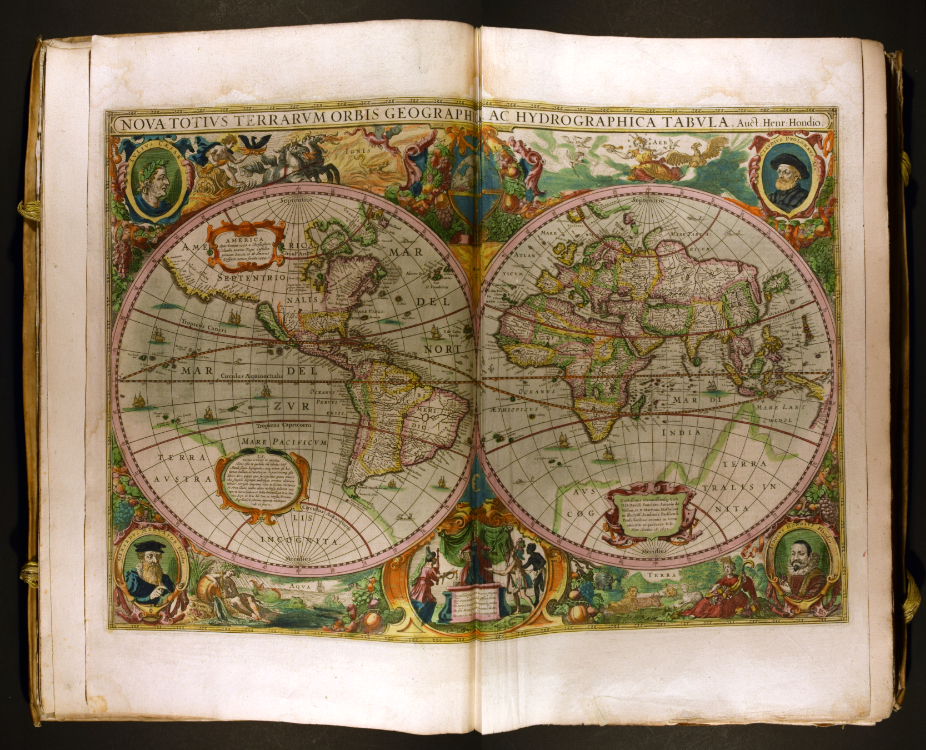

Nova Totivs Terrarvm Orbis Geographica AC Hydrographica Tabvla, in Atlas Novus, Volume 1

Hendrik Hondius (1597–1651)

Amsterdam, 1638

Hand-colored engraving on paper

20 1/2 x 13 x 3 in. (52.1 x 33 x 7.6 cm)

University of Delaware Special Collections, Folio+ G 1007 .A7 1638

The very core of the universe was in question. In a time of drastic scientific change, Hendrik Hondius clung to tradition. When this map was made, Europe was in the midst of a major shift started by mathematician and astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543). Copernicus asserted that the earth was not the center of the universe. In fact, he declared that the universe bears no one center. But Hondius had other things on his mind: he had to maintain the family business.

In a race to compete against a rival publishing house, Hondius produced this map with up-to-date geography. While innovative for its inclusion of the Australian coastline and Korea’s position as an isthmus, this map’s order of the universe recalls long held beliefs. Many of these date back to Claudius Ptolemy (c. 100–c. 170 BCE), pictured in the map’s upper right. He assumed that the earth was the unmoving center of the universe. The lower right corner holds the portrait of the mapmaker’s father, Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612), to accompany the other notable geographers. In so doing, Hondius traces a lineage of mapmakers from ancient Rome to his own family. Through this elaborate peripheral decoration, he wields tradition to claim authenticity for his map, avoiding the risks of contemporary controversy.

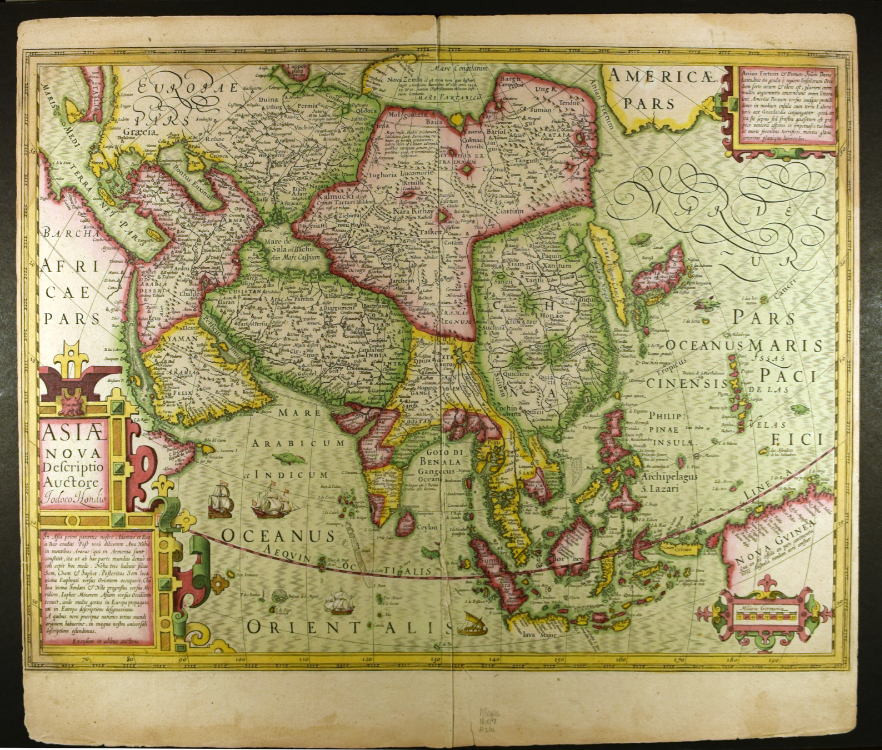

Asiae nova descriptio

Jodocus Hondius (1563–1612)

Amsterdam, 1607

Hand-colored engraving on paper

17 1/2 x 20 in. (44.5 x 50.8 cm)

University of Delaware Special Collections, 01807 gr

Though depicting Asia, this map connects the entire human world. Woven with myth and religion, the Dutch mapmakers present their order of the universe. Two corner text blocks reveal these perspectives.

In the lower-left, Latin text places humanity’s origins in Asia. It states that God created Adam and Eve, the first humans, there. Additionally, the text places Noah’s ark in Asia, referencing the large boat that saved enough people and animals to repopulate the world after a global flood. It was thought that Noah’s three sons fathered three races, leading to harmful, long held beliefs about racial hierarchy.

This desire to categorize people motivated another critical early modern myth. The text in the upper-right describes the well-accepted, yet to be confirmed, Northwest passage to Asia. This stretch of water called “Anian Fretum” lies just west of its description on the map. Seventeenth-century explorers believed in a perfectly balanced cosmos where the northern and southern hemispheres mirrored each other. Following this logic, because straits at the tip of South America were found, a northern maritime passage had to exist. Their belief that Indigenous peoples of the Americas migrated from Asia also added weight to Europeans’ obsession. Many ships sank in pursuit of this elusive route to Asia.

For additional information on European perceptions of the other continents in the early modern period, please see Mercurio Geografico: Pictorial Separation by Erin Hein.