Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) is one of the most heavily forged of all American artists. Even in his own lifetime, forgeries of his paintings abounded, a point that Ryder himself was well aware of. Today there are more fraudulent Ryder paintings than there are genuine ones in existence. Ryder had a comparatively small artistic output, especially later in life, at a time when his works already commanded high prices. This gave forgers an obvious profit incentive. His style was relatively easy to imitate, at least on a superficial level. Many forgers either imitated existing, genuine Ryders, or selected recurring images and topics that he would likely have painted. In 1913, the Armory in New York City held a major exhibition of his work and, after his death, his works increasingly appeared in public galleries, giving would-be forgers easy access to genuine paintings that could be used as models. Eventually, Ryder forgeries became so common that many forgers were likely basing their forgeries off of other forged paintings.

In 1935, Lloyd Goodrich (1897-1987), then a curator at the Whitney Museum in New York, visited a Ryder exhibit and came away with serious concerns about the authenticity of the paintings on display. In an attempt to set the record straight, Goodrich began a comprehensive study of Ryder. He started by identifying Ryder paintings that could be verified based on provenance and other objective evidence. He examined these paintings under x-ray, microscope, and ultraviolet light, and used his findings as a means by which to authenticate other Ryders. Ryder produced his paintings by using a slow and pain-staking technique in which he would build up multiple layers of pigment and glaze. Forgers, who were trying to quickly produce work to sell for a profit, would, at best, try to imitate this without taking the necessary time and effort, as could readily be seen when a painting was examined under x-ray.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

Elegy, oil on canvas, [no later than 1924; probably no earlier than 1880-1885]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

Llyod Goodrich examined Elegy in 1967, while it was on loan to the Whitney. On the surface, Goodrich thought the painting came “close to the general ‘Ryder style,’.” An x-ray analysis showed that the painting had only a general preparatory surface and a uniform layer of brushstrokes. It lacked the multiple layers of paint that would be found in a genuine Ryder, making it most certainly a forgery. Goodrich concluded that this was “an early one, probably, and a good one, but still not genuine.” Elegy appears to have been painted in imitation of a genuine Ryder painting, The Lone Horseman (ca. 1880-1885). Elegy is one of several such imitations, and many of them were so similar in style and composition that they were probably produced by the same forger. (Goodrich thought that the forger behind Elegy was also responsible for The Horseman, also on display in this gallery.)

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

Industry, oil on panel, [circa 1884?; no later than 1935]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

This painting purports to be a work by the American artist Albert Pinkham Ryder, but it is actually a fake. Lloyd Goodrich, an expert on Ryder, analyzed Industry in 1937 and dismissed it on stylistic grounds. He thought the figures were “very badly drawn and executed,” to the point that “this must have been done by an artist who had not even the competence of a third-rate professional.” The painting’s color scheme was “not characteristic of Ryder.” Finally, the forger had attempted to make do with a crude imitation of Ryder’s painting technique, which involved using multiple layers of paint to create an image. In producing an imitation of this, the forger appears to have first coated the panel with random “gobs of paint” and then painted a finished image over them.

This painting was sold at auction in 1935. The sales description for the auction alleged that it had been purchased directly from Ryder by Louis F. Prang (1824-1909), an American lithographer. This does not confirm that the painting is genuine: many forgers fabricated a provenance to go alongside their paintings to make them seem more believable. The auction listing also stated that Industry was displayed as a Ryder at the New England Manufacturer’s & Mechanic’s Institute Exposition in 1884. The catalog for the Exposition does list a Ryder painting by this name, but the catalog listing is not illustrated, making it impossible to verify if this is the painting that was exhibited there. If true, though, this would mean that this forgery was mistaken for a genuine Ryder painting while the artist was still alive. Ironically, the Exposition was intended to showcase the greatest accomplishments in all of American art for that year.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

Quietude, oil on canvas, [circa 1914–1918]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

Lloyd Goodrich examined Quietude in 1956 and 1957. At first he thought this was most likely a genuine Ryder due to its style. Closer examination raised some doubts, but, he later wrote, “it seemed closer to Ryder than any problem picture I had examined.” He noted that it was also very similar in style, technique and color to a series of early forgeries, all of which date back to at least 1920. (Quietude first appeared on the market in 1918). Quietude is also very similar to a genuine Ryder painting, The Shepherdess, which had been exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum from 1914 onwards, allowing opportunity for a forger to copy it. An x-ray raised further doubts, revealing an irregular undersurface beneath the painting, suggesting that an earlier painting was scraped off of the canvas and then further cleaned off with a solvent, providing a canvas that would look old enough for a Ryder. Goodrich spent over a month examining Quietude. He felt it was “the most puzzling ‘Ryder’” that he had ever come across.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

Sailing by Moonlight, oil on panel, [no later than circa 1894; probably no earlier than ca. 1880-1885]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

This painting comes with a seemingly good provenance: it passed through the firms of William Macbeth and Robert C. Vose, both of whom were early champions of Ryder, and sold a number of his paintings in the early twentieth century. Prior to them, Sailing by Moonlight’s ownership in private hands can be traced back to about 1894. The painting was authenticated by three members of the American Art Dealers Association in 1932. However, Goodrich, having examined a great number of other Ryder’s, both genuine and fraudulent, concluded otherwise. The forger tried to imitate Ryder’s technique of using multiple layers of glaze to construct a finished image, but did so without putting anywhere near the same amount of effort or labor into it. Instead, it has a fairly smooth and even surface, suggesting it was probably painted all at once. On a more subjective, stylistic level, Goodrich also thought the drawing was much more crudely formed than anything Ryder would have painted, though it still displayed enough technical skill to be more convincing than most forgeries. He thought it was likely that the painting had been based on a genuine Ryder, Toilers of the Sea.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

A Spanking Breeze, oil on canvas, [no later than circa 1935]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

An x-ray of A Spanking Breeze shows that this was painted over another landscape. The artist selected one of Ryder’s common themes – a boat at sea, under a moonlit sky – as was typical of many other Ryder forgeries. Goodrich dismissed this piece as “an obvious fake.”

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

The Storm, oil on canvas, [no later than 1930; probably no earlier than 1909]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

The Storm is an example of a particularly bad forgery. Its provenance already gives cause for suspicion. There are no published references to it dating to Ryder’s lifetime and the first mention of it is when it was being offered for sale by the Ferargil Gallery in 1930. Ferargil has long been associated with Ryder forgeries, and so any painting that was offered by them – especially one that appeared at the gallery with no earlier trace of its existence – is suspect. The reverse of the painting has what purports to be a presentation inscription from Ryder, although Goodrich thought the handwriting was unlike Ryder’s. The name of the recipient is indecipherable, which may have been intentional, so as to create the appearance of a clear provenance without actually allowing one to easily verify its accuracy. As early as 1936, Frederic Fairchild Sherman (who wrote the first monograph on Ryder) had denounced The Storm as a fake, and Goodrich followed suit two years later. In 1977, an examination of the pigment and an x-ray further confirmed the painting’s fraudulence. It is very similar to The Smuggler’s Cove, an authentic Ryder, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1909 onwards, but it lacks Ryder’s usual technique of mixing layers of oil paint, glaze and varnish. The cracks in the paint further expose it as a hastily made fake. Ryder’s real paintings often exhibit cracks, caused by premature aging, partly because he would often paint over areas before they were fully dry. This resulted in complex structures, produced by a combination of shrinking and other mechanical processes. Forgers tried to imitate this, sometimes by rolling or baking their paintings, other times by painting in cracks, as appears to the case here, resulting in an especially sloppy effect.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

The Horseman, oil on panel, [no earlier than 1880-1885]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

As with Elegy (also on view in this gallery), The Horseman appears to have been painted in imitation of a genuine Ryder painting, The Lone Horseman (as reproduced below). Goodrich thought that these paintings may have been produced by the same forger. If so, this is probably an earlier effort, and the two paintings allow one to see the evolution of this forger’s technical skills. Elegy displays a much greater degree of sophistication than this painting. Goodrich dismissed The Horseman as “crude and insensitive and amateurish.” Goodrich also thought that the Ryder signature here “looks more neat and tidy than Ryder’s genuine ones,” suggesting that the forger was trying too hard to imitate Ryder’s script.

Forgery of Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

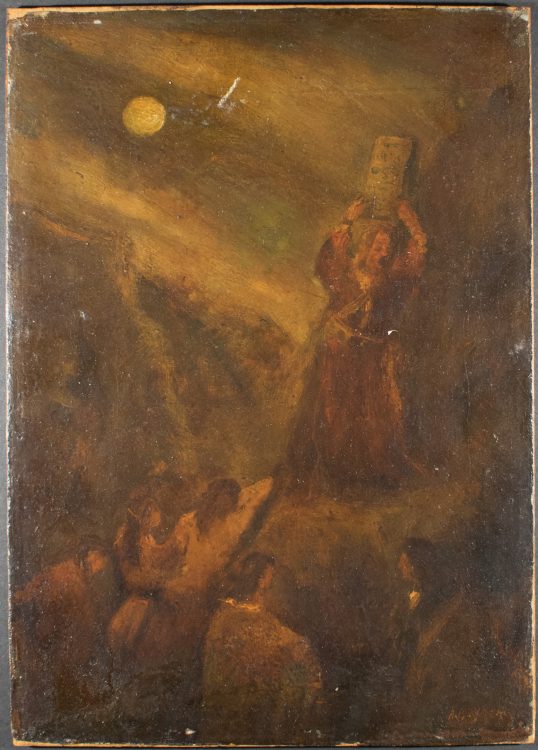

Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law, oil on panel, [no later than 1938]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

X-ray scan of Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law, revealing an older, undated painting beneath. X-ray scan taken in 1943

Goodrich was frank in his critique of this painting: “The handling is dashing and quite sloppy. The picture appears to have been painted with a full brush. The drawing is horrible, quite incompetent. No feeling for form in the picture. No detail or fineness; everything is just slopped in. Altogether one of the worst fakes I have seen.” Goodrich first viewed the painting in 1938, and pronounced it a fake on stylistic grounds alone. In 1943, a collector showed him the same painting, which he had bought from a dealer who had advertised it as genuine. This time, as a further test, Goodrich had this painting x-rayed at New York Hospital. The x-ray (which is reproduced below) revealed that there was a damaged painting of a child beneath this one, in a style completely unlike Ryder’s. The forger probably used that painting as a base because it made the forged Ryder painting look older than it really was.

Forgery of or mis-attribution to Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917)

[Untitled sketchbook], pencil on paper, [circa 1882?]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

This sketchbook contains twenty-eight sketches of scenes from Venice and other European cities. It was once thought that Albert Pinkham Ryder drew them in 1882, while travelling through Europe and Tangier with his dealer, Daniel Cottier (1838-1891), and the sculptor Olin Warner (1844-1896). Philip Evergood (1901-1973) acquired the sketchbook from the home of Louise Fitzpatrick in 1934, and then gave it to Lloyd Goodrich (1897-1987). Louise Fitzpatrick was a close friend and pupil of Ryder’s, and he also lived with Louise and her husband, Charles, during the final years of his life. Thus, it was certainly probable that she could have had a Ryder sketchbook in her possession. As of 1939, Goodrich had concluded that the Ryder attribution was incorrect. Because we have no record of how Fitzpatrick obtained the sketchbook, nor of when or why it was attributed to Ryder, it is unclear whether this was an intentional forgery or just a case of mistaken identity.

![[Untitled sketchbook] [Untitled sketchbook]](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/things-arent-what-they-seem/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2019/10/sketchbook-e1579642876937.jpg)