Forgery of Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919)

Evening, oil on panel, undated, [probably late nineteenth or early twentieth century]

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

Blakelock’s paintings received little attention while he was actively producing them. He lived most of his life in poverty and struggled to support his family. In 1891 he experienced a mental breakdown and spent most of his remaining life in state mental hospitals, suffering from depression and schizophrenia. His fame and popularity grew only after his institutionalization, and his paintings, which he once sold for a pittance, began selling for enormous sums. Because there were a limited number of genuine Blakelock paintings on the market, forgers capitalized on his newfound popularity, producing a multitude of imitations for sale, so much so that he holds the dubious distinction of being one of the most widely forged painters of his day. In addition to fabricating new artwork, forgers would also select genuine paintings by artists who had painted in a similar style, and then forge Blakelock’s signature so as to create a more valuable piece. (Perversely, some dealers did this to paintings by his own daughter, Marian Blakelock, which led her to stop painting altogether). Blakelock forgeries can usually be debunked based on stylistic grounds. Unlike his real work, the forgeries were produced in haste by people trying to imitate his typical subject matter, and they tend to be crude by comparison. For example, the transition from light to dark portions of the canvas tends to be awkward, and the foliage in trees is often less defined. In this painting, the signature is also over-pronounced, and appears to have been done by someone trying too hard to imitate Blakelock’s letter forms.

Forgery of A. H. Wyant (1836-1892)

Landscape, oil on panel, undated

Lloyd Goodrich and Edith Havens Goodrich Papers Relating to Albert Pinkham Ryder

Originally attributed to the American artist A. H. Wyant, this painting was deaccessioned from an American art gallery after Lloyd Goodrich rejected its authenticity.

Probable forgery of Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796-1875)

“Landscape Sketch,” oil on panel, undated

Museums Collections, Gift of Mr. Van R. Coats

Originally trained as a draper, Corot took up painting as a hobby in 1821. A year later, an inheritance allowed him to focus solely on his artistic ambitions. Corot grew to become an incredibly popular artist, particularly in the last decades of his life. His popularity also inspired other, unknown artists to produce a great number of fraudulent Corot paintings, so much so that he became one of the most widely forged painters of the nineteenth century. His forgers were aided by the fact that there were already a great number of Corot paintings on the market, which supplied them with a number of landscapes they could imitate. Corot himself was actually a bit ambivalent about this. It’s believed that he may have even touched up some of the forgeries and claimed them as his own work. Additionally, he sometimes touched up artworks by his students, further complicating the task of authenticating alleged Corot paintings.

Although this painting has not been conclusively identified as a forgery, its provenance is shaky, making it unlikely that Corot actually painted it. In 1932 it appeared in a Samuel T. Freeman & Co. auction catalog; allegedly, a Mrs. Clarkson Carroll had received it from her father in 1911. There is no earlier known record of the painting’s existence. It has not yet been subjected to chemical tests. An analysis of the painting’s pigments and varnish, as compared to those found in genuine Corot paintings, might allow us to rule it out as a fake if it turned out that the painting’s chemical composition was atypical or anachronistic of the materials used by Corot. This would not, though, allow us to validate the painting as genuine, as it still could have been painted by someone who was imitating Corot’s style and using his same materials.

Forgery of Adolphe Monticelli (1824-1886)

Untitled (still life with flowers), oil on panel, undated (circa 1870s or 1880s)

Museums Collections, Gift of an Anonymous Donor

Today, Monticelli is probably best known for role in inspiring the work of Vincent Van Gogh. Forged Monticelli paintings were identified in the market as early as 1881, while the artist was still alive. His popularity increased after his death, with his paintings selling for enormous sums. The increased demand created an even greater profit incentive for artists to produce forgeries painted in his style. Monticelli’s own practices compounded the problem. Sometimes he sold unfinished paintings to friends and other artists, who could then finish a painting and present it as if it was all Monticelli’s doing. He also did not maintain records of what he had actually painted, which makes it all the harder to authenticate his work.

This painting is believed to be a forgery, although recent research suggests that it was probably produced by someone closely associated with Monticelli and his circle. This is in keeping with other known Monticelli forgeries, many of which were produced by close friends of the artist after his death. A scientific analysis of the painting’s composition confirms that it was painted in a manner consistent with Monticelli’s practices. An analysis of a paint sample from this painting shows that the paints contain resins, waxes, and asphaltum, all ingredients that were often used by nineteenth century painters in France and England. The painting is also executed on the same kind of material that Monticelli used: a wood panel, taken from a piece of disassembled antique furniture. Although a fake, this painting is very convincingly constructed.

Forgery of Paul Signac (1863 – 1935)

View of a Harbor, oil on canvas, probably early twentieth century

Museums Collections, Gift of Robert W. Birrell

This painting was created in the style of Paul Signac, and is similar to the kinds of scenes that he painted. It was probably also produced at the same time that Signac was active. It is not, however, an original work by Signac, and the Signac signature on the painting is fraudulent. It is not clear whether the painting was produced as an intentional forgery, or if someone later supplied the fake Signac signature in the hopes of amplifying the painting’s commercial value.

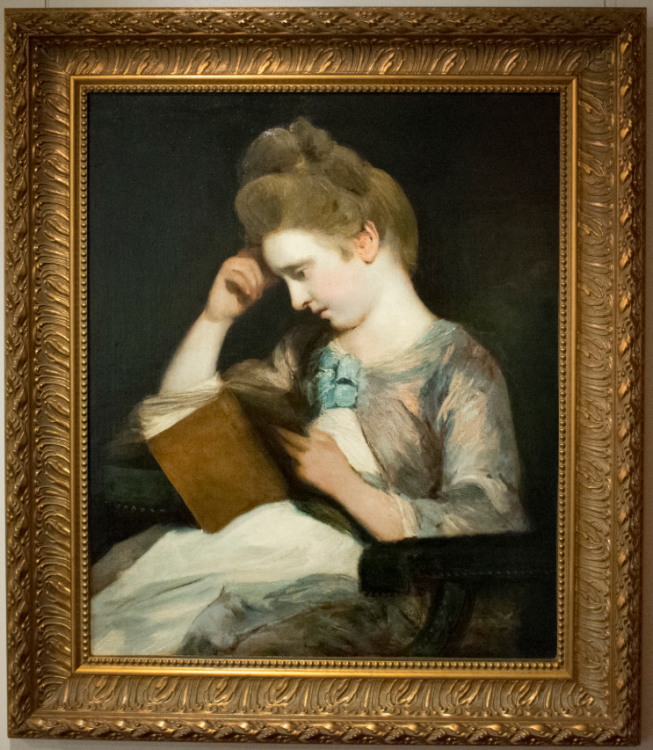

Unknown copyist, after Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792)

Portrait of Theophila Palmer, oil on canvas, undated

Museums Collections, Gift of an Anonymous Donor

While most of the paintings on display in this gallery are new paintings that attempt to mimic the style of other famous artists, this painting is an exact copy of one that Sir Joshua Reynolds painted in 1771. Unlike the others, this painting is almost certainly not an intentional fake. Copying is a common element of artistic education; by imitating another piece of artwork, a student can try to understand an artist’s technique and incorporate that into his or her own skillset. These copies only become problematic if they are misrepresented as or mistaken for genuine examples of the original artist’s work. Cases of mistaken identity become more likely after the piece has passed beyond the ownership of the original copyist. Subsequent owners, either through ignorance or wishful thinking, may mistake it for being much more than what it is.

Possible Forgery of Thomas Cole (1801-1848)

Swiss Landscape, oil on canvas, [circa 1820-1848?]

Museums Collections, Gift of an Anonymous Donor

The origins of this painting are uncertain. It was originally sold as a painting by Thomas Cole, an American romantic landscape painter and a founder of the Hudson River School. After doubts arose about its authenticity, the painting was bought back by the dealer and later donated to the University of Delaware as an example of a possible fake. Lacking any clear details of its provenance, we do not know if it was painted as a deliberate forgery, or if it was simply painted in Cole’s style with no attempt to deceive.

Possible Forgery of Théodore Rousseau (1812-1867)

Watching Cattle, oil on canvas, [circa 1840-1890?]

Museums Collections, Gift of an Anonymous Donor

This painting was originally attributed to the French painter Théodore Rousseau, one of the leaders of the Barbizon school of landscape painting, but its authenticity was called into question after it had been sold by an art dealer. Unable to conclusively verify whether or not it was fraudulent, the dealer repurchased it and eventually donated it as a teaching example of a possible forgery.

Possible Forgery of J. F. Millet (1814-1875)

Woman with a Stick Bundle on Her Back, oil on canvas, [circa 1860-1899?]

Museums Collections, Gift of Margaret W. Litt

This painting was donated to the University of Delaware in 2004. Although initially attributed to Millet, a French painter and founder of the Barbizon school, the lack of a clear provenance has left us unable to verify its authenticity. Authenticating Millet’s work is especially problematic, since he has been was a known target for forgers. In particular, his own grandson, Jean-Charles (1892-1944) was arrested and convicted for selling fraudulent paintings attributed to Millet.