This part of the exhibition brings together a range of items from the Black Power and Black revolutionary movements of the 1960s. Also included are a few texts representing the philosophy of non-violence, which was also an important element of the civil rights movement during that period.

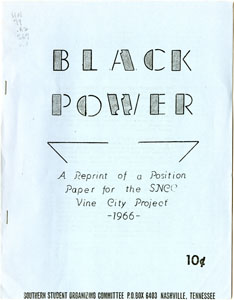

Southern Student Organizing Committee

Black Power. Nashville, Tenn.: Southern Student Organizing Committee, 1966[?]

This booklet is a reprint of a position paper put out by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an important 60s era civil rights group that first came to prominence during the 1961 Freedom Rides. In 1966, when Stokely Carmichael became chairman, the group moved away from a strong emphasis on nonviolent struggle and interracial cooperation, both of which had characterized its earlier years. Carmichael’s call for Black power emphasized the importance of Black leadership and control of organizations such as SNCC, with less input from whites. This position put the group at odds with more moderate civil rights organizations, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Martin Luther King, Jr., 1929 -1968

Where do we go from here: chaos or community? New York: Harper & Row, 1967. First edition.

This book contains a direct response to the Black Power strategy coming out of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Here King writes, “effective political power for negroes cannot come through separatism.”

Bayard Rustin, 1912-1987

“Nonviolence in the South.” New York: War Resisters League, 1957.

Rustin was the most accomplished American strategist of non-violent resistance, having trained Martin Luther King and other leaders. This pamphlet was written in the 1950s as a “report with suggestions” on the training Rustin was doing in various parts of the South, in support of the Montgomery Bus boycott and other protests. Rustin’s identity as a gay man caused him at times to be sidelined as he carried out his civil rights organizing work. This was particularly true at the time of the 1963 March on Washington, of which he was the main organizer.

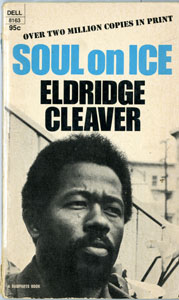

Eldridge Cleaver, 1935-1998

Soul on Ice. New York: Dell, 1968. First edition. From the library of Littleton B. Mitchell.

Cleaver had quite a varied career as a revolutionary, eventually becoming a conservative born-again Christian. Soul on Ice is his best known book, composed of reflections on the time he spent in prison, thoughts on the status of Black people in America, and a particularly conservative take on gender relations and gay issues. At the time he wrote the book, Cleaver was a member of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, which espoused the views of Malcolm X and Marxist Leninist socialism, in the belief that community organizing and armed struggle would lead to an end of capitalist exploitation and an equitable redistribution of wealth.

Clarissa Sligh, 1939

Transforming Hate: an Artist’s Book. Asheville, North Carolina: Clarissa T. Sligh, 2016.

Clarissa Sligh is a well-known African American book artist and photographer. This recent book is part of a project in which artists were asked to create works using copies of The White Man’s Bible, a white supremacist document. Using text and photographs, Transforming Hate documents how Sligh used The White Man’s Bible to create hundreds of beautiful origami doves. Sligh’s book also recalls her personal experiences with racism as a child in the Jim Crow South, and later as an activist in the civil rights movement.

Malcolm X, 1926-1965

Alex Haley, 1921-1992

The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Grove Press, 1964. First edition. Author’s autograph presentation copy.

This bestselling book has at times received criticism on account of the heavy editorial influence of co-author Alex Haley. Nonetheless, it has been an influential source of information on the life of Malcolm, describing his transformation from criminal to prison inmate to spokesperson for Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. A pivotal section explains his move away from separatism, after his pilgrimage to Mecca. Malcolm’s growing prominence was followed by a rupture with Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. The Autobiography appeared shortly before his assassination in 1965.

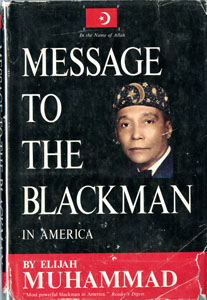

Elijah Muhammad, 1897-1975

Message to the Blackman in America. Chicago: Muhammad Mosque of Islam No. 2, 1965. First Edition

The leader of the Nation of Islam wrote this book in 1965. The Black nationalist philosophy it presents is based on a particular interpretation of Islam. In this view, Blacks were the original humans and the white race emerged from a scientific experiment gone awry. Separation of the races is the solution Muhammad proposes. Message to the Blackman also devotes numerous chapters to describing how African Americans should understand their proper place and function in America.