While the Harlem Renaissance (or New Negro Renaissance) was largely an urban phenomenon of the 1920s and 30s, New York was far from the only place were African Americans came together to discuss ideas and collaborate. Philadelphia, Washington D.C., Chicago, and other places also saw the establishment of salons and literary magazines. What writers and artists in the various places shared was the aim of defining African Americans in a way that went against the numerous racial stereotypes that had been perpetrated against them. Establishing and defining “Negro Literature” and “Negro Art” were major aspects of the goal. At the same time, there were debates regarding just what aspects of Black life should be represented, and how.

Alain LeRoy Locke, 1885-1954

Winold Reiss, 1886-1953

The New Negro: an Interpretation. New York: A. and C. Boni, 1925. First edition.

According to the Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, “New Negroes were middle class, demanding of their civil rights and they wanted to develop new images to replace old stereotypes.” In The New Negro, Alain Locke and his collaborators emphasized culture as the domain for this type of social redefinition. The lengthy book contains contributions by many writers, scholars, and artists. However, a certain tension around social class is evident. At certain points, the book suggests that less privileged members of the race were leaders in the new self-definition of Blacks. Langston Hughes was a champion of this vision. However, at other points emphasis is place on more elite Blacks, representatives of Dubois’ Talented Tenth.

Survey Graphic

Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro. New York: Survey Associates, 1925.

In 1925 the magazine Survey Graphic devoted one issue to Harlem, “Mecca of the New Negro.” Containing poetry, essays, fiction, and artwork, it laid out some central themes of the Harlem Renaissance: the battle against racism, African Americans’ contribution to the arts, and their connection to nationalist movements in other countries. The list of contributors included Alain Locke (who also edited the issue), James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, Angelina Weld Grimké, W.E.B. Dubois, Eunice Roberta Hunton, Anne Spencer, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, J.A. Rogers, Elise Johnson McDougald, and others. The Harlem issue of Survey Graphic was the basis for the better-known anthology, The New Negro, which can also be seen in this section of the exhibition.

Wallace Thurman, 1902-1934

Fire!! Metuchen, NJ; Fire!! Press, 1092. Facsimile edition, signed by Richard Bruce Nugent.

Conceived by authors Langston Hughes and Richard Bruce Nugent, Fire!! was a statement of youth to their elders. By evoking topics such as homoeroticism and street life, Fire!! shifted from the middle-class focus of Dubois’ ideal, the Talented Tenth. The editorial team included novelist Wallace Thurman, Zora Neale Hurston, and artist Aaron Douglass, who created innovative illustrations. Poetry, fiction, drama, and essays were contributed by Hughes, Nugent, Countee Cullen, Dorothy West, and others. Dubois and other Black critics were displeased by Nugent’s homoerotic story “Smoke Lillies and Jade.” The magazine appeared only once and a large number of copies of the issue burned in a fire. However, Fire!! is now considered a key document of the Harlem Renaissance.

Jessie Redmon Fauset, 1882-1961

The Chinaberry Tree. London: Mathews & Marrot, 1932. First edition.

As literary editor of the Crisis (the magazine of the NAACP), Fauset aided the development of many Harlem Renaissance writers, including Langston Hughes and Wallace Thurman. The Chinaberry Tree (the third of Fauset’s four novels) tells the story of Sal Strange, a Black woman who has a daughter with a wealthy white businessman, who refuses to marry her. The novel describes the search for love among the women of Sal’s family, which is privileged, but also set apart from the African American community by the interracial relationship which brought it into being. All of Fauset’s novels examine the intersection between race, class, and gender among members of the African American middle class.

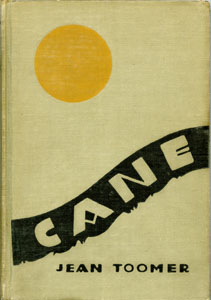

Jean Toomer, 1894-1967

Cane. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1923. First edition.

Considered by many to be a masterpiece of the Harlem Renaissance, Cane is experimental in form, combining poetry and prose in a manner that had not been seen before (and that annoyed some critics, such as W.E. B. Dubois). The work is an exploration of southern, African American culture. Liberating sensuality and spiritual wholeness are associated with the South, in contrast to the intellectualism of the North. Toomer believed that this vibrant southern culture was in the process of disappearing due to industrialization, and the novel presents African American characters who reflect various ways of being linked to this social transformation.

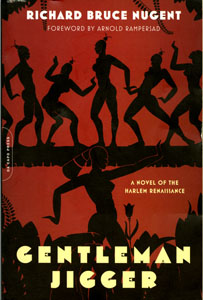

Richard Bruce Nugent, 1906-1987

Gentleman Jigger. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo, 2008. First edition.

Gentleman Jigger was first published in 2008, after the author’s death. It is the only known novel of Richard Bruce Nugent, a key figure in the core group of Harlem Renaissance writers, whose essay “Lilies, Smoke and Jade” appeared in the magazine Fire!! That story is the first by an African American to feature a bisexual character, as part of a creative exploration of sexuality and race. Gentleman Jigger (a roman à clef)describes the gatherings and interactions of the Harlem Renaissance group, but also relates the sexual (mostly gay) experiences of onemember of that group, the semi-autobiographical character Stuart Brennan.

Nella Larsen, 1891-1964

Quicksand. New York; London: A.A. Knopf, 1928. First edition. From the library of Alice Dunbar-Nelson.

Quicksand, Larsen’s first novel, was praised as one of the finest of its time, and it catapulted the author into prominence in Harlem Renaissance circles. The work is largely autobiographical, drawing on the author’s difficult experiences as the daughter of a white Danish American mother and a Black West Indian father, growing up in racially segregated Chicago. Quicksand describes the biracial protagonist Helga’s failed attempts to find a place in American society, either among whites or Blacks.