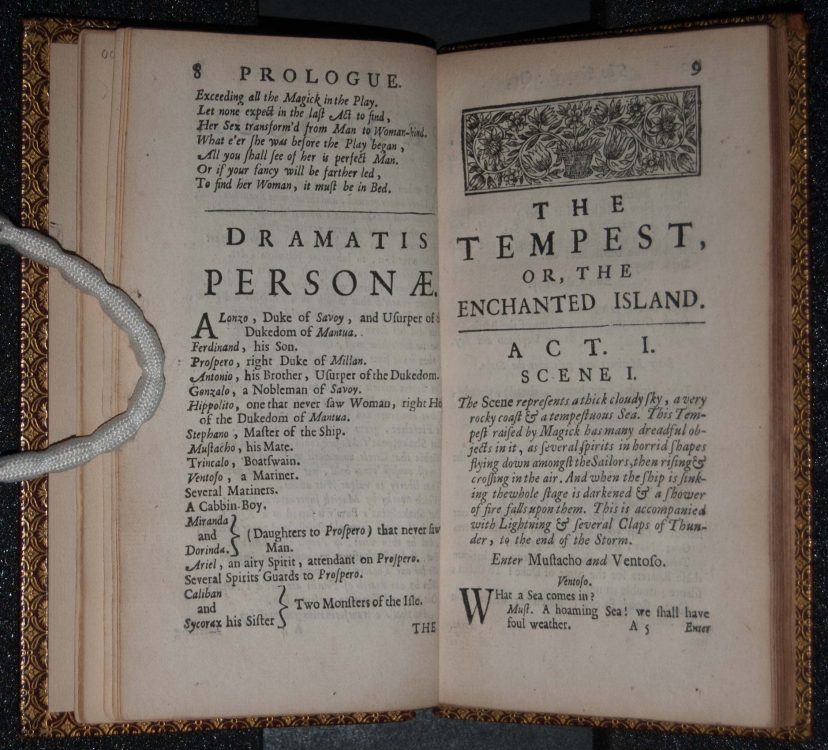

William Davenant (1606-1668) and John Dryden (1631-1700)

The Tempest, Or, the Enchanted Island: A Comedy. London [i.e. The Hague: s.n.], 1710.

Written as a collaborative effort between William Davenant and John Dryden, The Tempest, Or, the Enchanted Island was an incredibly successful adaptation of Shakespeare’s play. It was first performed in 1667, and first published in 1670. In 1674, the play was further altered by Thomas Shadwell (ca. 1640-1692), who transformed it into an opera, complete with stage machinery, singing, and dancing.

In adapting The Tempest, Davenant and Dryden retained portions of Shakespeare’s original text, but they simplified some of his language and grammar to better suit their audiences. They also introduced a host of new characters. As a parallel to Miranda, a woman who had never seen a man, they introduced Hippolito, a man who had never seen a woman. (In his preface, Dryden said that this was done so that, together as counterparts, the two characters could all “the more illustrate and commend each other.”) Prospero received a second daughter, Dorinda (who also had never seen a man before). Lastly, Caliban received a sister, Sycorax, who was named for Caliban’s mother, a character who is mentioned but never actually appears in the original play.

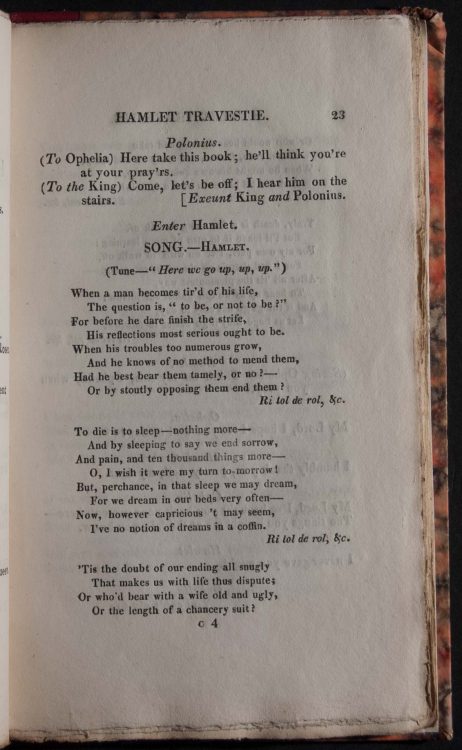

[John Poole (1786?-1872)]

Hamlet Travestie: In Three Acts. With Annotations by Dr. Johnson and Geo. Steevens, Esq. And Other Commentators. London: J.M. Richardson, 1810.

John Poole’s Hamlet Travestie was an extremely popular parody of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In his introduction, Poole insisted that Shakespeare’s works were so great that it was fine to poke fun at them, since there was no risk that a parody or mockery could ruin the enjoyment of the original. In this play, the texts and plots of Hamlet were blended with a mixture of contemporary colloquialisms and anachronisms, with much of the tragedy played to comic effect. For example, Hamlet’s “to be or not to be speech,” shown here, was recast as a song, played to the tune of “Here go up, up, up.” In place of the duel and poisoned chalice that brought Hamlet (and almost all of its characters’ lives) to a close, Hamlet Travestie ends with a boxing match and poisoned beer. Poole did not only make fun of Shakespeare himself. In the introduction, Poole wrote venomously about Shakespearean scholars and their tendency to produce increasingly pretentious and long-winded annotated editions in which one finds “his sense perverted, and his meaning obscured, by the false lights, and the fanciful and arbitrary illustrations, of Blackletter Critics and Coney-Catching Commentators.” Accordingly, the printed text of Hamlet Travestie included a series of critical footnotes intended to mock the critical and textual studies of Shakespeare’s own works.

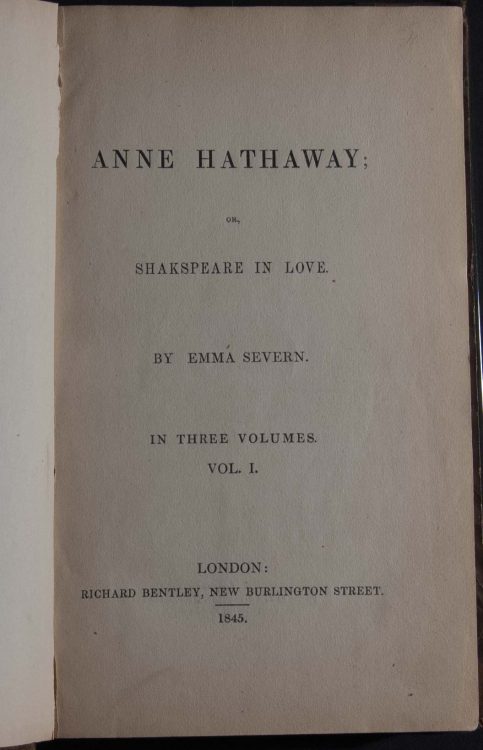

Emma Severn

Anne Hathaway, Or, Shakspeare in Love. London: R. Bentley, 1845.

Emma Severn’s Anne Hathaway was an early example of Shakespearean historical fiction. The novel presented a heavily idealized vision of Shakespeare’s marriage to Anne Hathaway (1555/6-1623), with Shakespeare cast as a romantic hero. In reality, as with most other elements of Shakespeare’s life, we have very little surviving evidence of any sort about Shakespeare’s marriage. This, of course, has led to all manner of speculation, and Severn’s novel was one of many examples of a desire to imagine a happy and idyllic domestic life for Shakespeare.

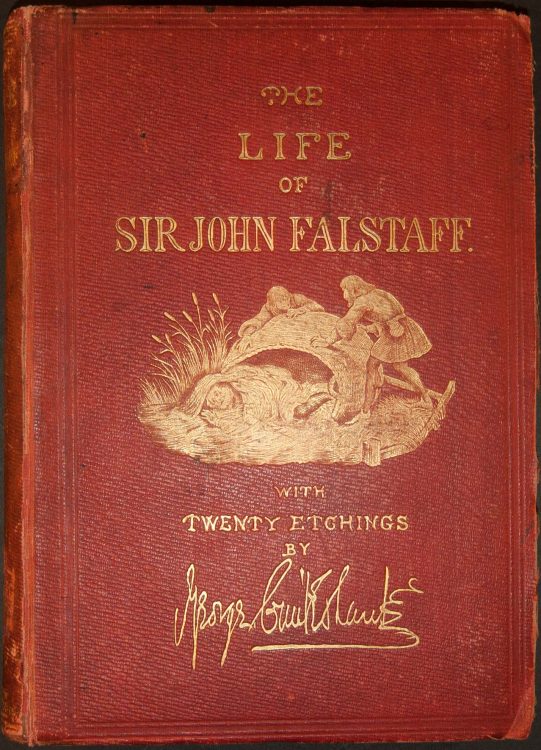

Robert B. Brough (1828-1860) and George Cruikshank (1792-1878)

The Life of Sir John Falstaff. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1858.

A collaborative effort between the writer George Brough and the artist George Cruikshank, The Life of Sir John Falstaff presented a fictitious biography of Falstaff, who had appeared in Shakespeare’s Henry IV Parts I & II and in The Merry Wives of Windsor. The narrative was spun out of the details included in Shakespeare’s plays and embellished from there. (In his preface, Brough wrote that, in Falstaff, Shakespeare had created a character so vivid that it was hard to imagine that he had not “actually lived and influenced the age he is assumed to have belonged to.”) The text was accompanied by twenty of Cruikshank’s illustrations. Unfortunately for Brough and Cruikshank, the book sold poorly. The production was further complicated by the fact that Brough missed many publishing deadlines due to his own ill health. Because the book was originally issued in parts, this, in turn, resulted in a sporadic publication schedule, which further hampered sales.

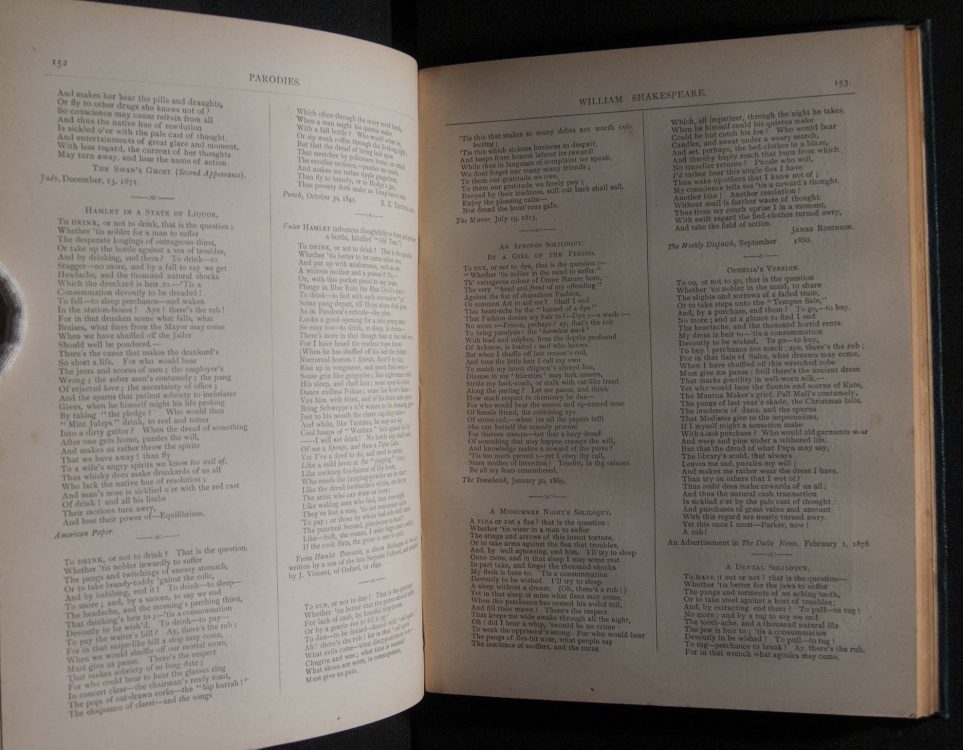

Walter Hamilton (1844-1899)

Parodies of the Works of English and American Authors. London: Reeves & Turner, 1885.

Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

This volume presented a compilation of parodies of English and American literature. Shakespeare’s works received particular attention: the index of titles to Shakespeare parodies is almost three pages long on its own. There are over fifty parodies of Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” speech, including such gems as “a Flea, or not a Flea?,” “to Pay, or not to Pay?,” “To be, or not to be Polite?,” and “To Drink, or not to Drink?” In introducing the section on Shakespeare, the editor reassured his readers that “not the slightest disrespect is intended, either to the works themselves or to that great author whose name, and fame, are dear to every Englishman.” Hamilton observed that, by this point in time, almost every Shakespeare play had received some kind of parody, and, anytime a Shakespeare performance was staged in London, a parody version was bound to appear almost immediately in response. Hamilton also noted that “there are many worthy people who take offence at this, and fail to see that such fun is of a very harmless description.”

Most of the Shakespeare parodies included in this volume are nineteenth-century productions, although there are also a few from the late eighteenth-century. In the introduction, the editor explained that, although there may be “some pieces which offend the taste” in this volume, “great care has been taken to exclude every parody of a vulgar or slangy description, although it need hardly be said that many such parodies exist.”