[William Henry Ireland (1777-1835)]

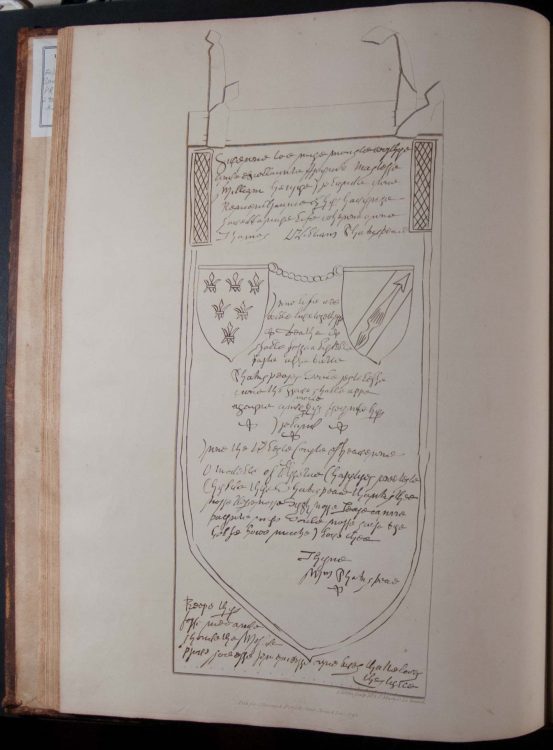

Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments Under the Hand and Seal of William Shakespeare: Including the Tragedy of King Lear, and a Small Fragment of Hamlet, from the Original Mss. in the Possession of Samuel Ireland, of Norfolk Street. London: Printed by Cooper and Graham […] Published by Mr. Egerton, Messrs. White, Messrs. Leigh and Sotheby, Mr. Robson and Mr. Faulder, and Mr. Sael, 1796.

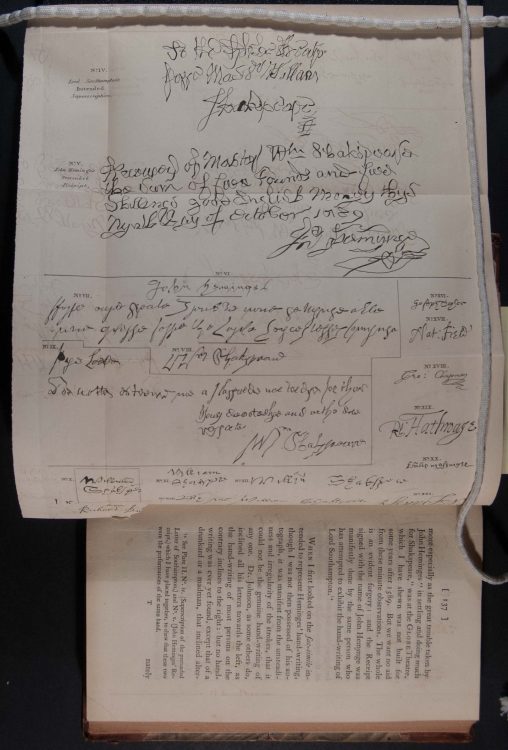

William Henry Ireland’s (1777-1835) father, Samuel Ireland (d. 1800), was a passionate Shakespearean, as well an obsessive (and gullible) collector of all things related to Shakespeare. In particular, Samuel Ireland yearned to own a specimen of Shakespeare’s own handwriting. (Today, there are six known surviving examples of his signature, and one possible manuscript fragment, so this would still be any collector’s dream.) William had once harbored literary aspirations, but he performed poorly in school, and even his parents seem to have thought little of him, his intelligence, and his future prospects. William worked as an apprentice in a law office, where he was often left unsupervised, with access to centuries worth of old legal documents. In December 1794, William “found” a legal document that was signed by Shakespeare and presented it to his father. William Henry Ireland had, of course, created Shakespeare’s signature by taking an old document and supplying an imitation signature based on a printed facsimile of a genuine one. Samuel took it to be authentic. Moreover, Samuel, who had always been distant from his son, offering William little in the way of warmth or affection, was ecstatic at the find. William explained that he had found the document in a trove owned by a “Mr. H.,” who had no interest in the documents himself and said that William was welcome to whatever he wanted. Samuel insisted that William find more -sometimes begging, other times demanding - and William complied, with increasingly exciting “finds.” He “found” a series of letters, including a love letter to Anne Hathaway (1555/6-1623) and a friendly letter from Elizabeth I (1533-1603) to Shakespeare. The “discoveries” got better and better still, with William producing annotated books from Shakespeare’s library, the manuscript of King Lear (which showed that all of the bawdy sections were not original to the play, but had been added by actors or later editors), and, finally, Vortigern, an undiscovered Shakespeare play (which had, of course, been composed entirely by William Henry Ireland). In Februrary 1796, Samuel displayed the documents to the public, and many people who should have known better took them to be authentic. Finally, William produced a document in which Shakespeare willed his writings to an Elizabethan by the name of William Henry Ireland. (Ireland, the document attested, had saved Shakespeare from drowning, and the writings were offered by way of thanks).

Ireland used this volume to publish transcripts and facsimiles of most of his Shakespeare forgeries. While many had viewed Ireland’s Shakespeare “manuscripts” when they were displayed at Samuel Ireland’s home, few had had a chance to scrutinize them in any serious detail. However, now that published copies were readily available, the critical response became increasingly skeptical. Still, the forgeries retained some supporters who insisted that they were genuine.

Edmond Malone (1741-1812)

An Inquiry into the Authenticity of Certain Miscellaneous Papers and Legal Instruments, Published Dec. 24, MDCCXCV, and Attributed to Shakspeare, Queen Elizabeth, and Henry, Earl of Southampton: Illustrated by Fac-Similes of the Genuine Hand-Writing of That Nobleman, and of Her Majesty: a New Fac-Simile of the Hand-Writing of Shakspeare, Never Before Exhibited: and Other Authentick Documents: in a Letter Addressed to the Right Hon. James, Earl of Charlemont. London: Printed by H. Baldwin for T. Cadell, Jun. and W. Davies (successors to Mr. Cadell,) in the Strand, 1796.

Edmond Malone was an esteemed literary scholar and biographer. In 1790, he had produced a new edition of Shakespeare’s works based on an extensive study of the quarto and folio editions. He had also spent many years examining the documentary record in order to expand and correct the details of Shakespeare’s biography. He denounced Ireland’s manuscripts as forgeries, and produced this scathing account in which he documented the many ways in which the documents were clearly fraudulent. He also reproduced additional facsimiles of the forgeries, paired with facsimiles of authentic documents, showing just how drastically different Shakespeare’s handwriting was from the handwriting found in Ireland’s manuscripts. All the more damaging, Malone’s Inquiry appeared in print just two days before the first performance of Vortigern, the “new” Shakespeare play that Ireland had “discovered.” Vortigern debuted and flopped before a packed crowd on April 2, 1796.