Gerard Langbaine (1656-1692)

An Account of the English Dramatick Poets. Or, Some Observations and Remarks on the Lives and Writings, of All Those That Have Publish'd Either Comedies, Tragedies, Tragi-Comedies, Pastorals, Masques, Interludes, Farces, or Opera's in the English Tongue. Oxford: Printed by L.L. for George West and Henry Clements, 1691.

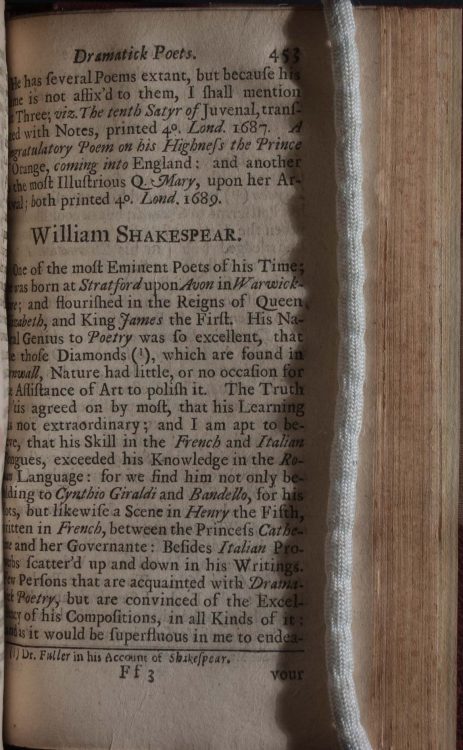

Langbaine’s Account of the English Dramatick Poets was the first systematic account of English plays and playwrights. Langbaine had previously published a series of catalogs of English plays, but this volume was far more ambitious than any of his previous works. The book presented brief biographical information, lists of each author’s plays, and an assessment of each playwright’s artistic significance. When possible, Langbaine identified the sources for each play and, in some cases, provided information about contemporary performance history. Langbaine singled out Shakespeare for particular praise: introducing Shakespeare as “one of the Most Eminent Poets of his Time,” he wrote that it would be an “injury beyond pardon” to compare Shakespeare with any of the playwrights “of our Age” and concluded that “I esteem his Plays beyond any that have ever been published in our Language.” Langbaine did not add much in the way of biographical details, although he did claim that Shakespeare had received little in the way of a formal education and that all of his skill in poetry had necessarily been born out of “natural genius.” Unfortunately, Langbaine did not provide any sources for this account, so, given that Langbaine was writing seventy-five years after Shakespeare’s death, it is difficult to gauge the accuracy of his narrative. It is also hard to tell what effect Langbaine’s book actually had on Shakespeare’s critical standing in its day: his book was printed in Oxford (most of the book trade was centered in London), and only one contemporary Shakespeare critic is known to have cited Langbaine’s volume.

David Erskine Baker (1730-1767)

The Companion to the Play-House: Or, an Historical Account of All the Dramatic Writers (and Their Works) That Have Appeared in Great Britain and Ireland, from the Commencement of Our Theatrical Exhibitions, Down to the Present Year 1764. Composed in the Form of a Dictionary, For the More Readily Turning to any Particular Author, or Performance. London: T. Becket and P.A. Dehondt, 1764.

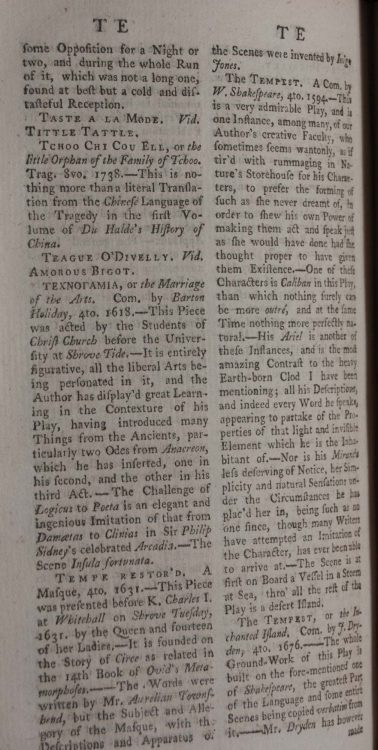

The Companion to the Play-House was a comprehensive account of British theater up to the present day. The first volume presented a catalog of every British play, with critical summaries and information about publication and performance history. The second volume contained biographies of all of the dramatic writers and several major actors. Baker accorded particular praise and attention to Shakespeare, whom he introduced as the “great Poet of Nature, and the Glory of the British Nation.” While Langbaine’s 1691 biography had contained little beyond Shakespeare’s birth and death in Stratford, the narrative had expanded quite a bit by the time that Baker produced his account. Unfortunately, Baker also did not cite any sources. Among other things, Baker wrote that Shakespeare had intended to enter the wool-trade, but he ran into trouble after he and his friends were caught poaching deer from Sir Thomas Lucy (ca. 1532-1600), who subsequently had them whipped. According to the story, a young Shakespeare responded with a ballad so pointed and venomous “that it became unsafe for the author to stay any longer in the country,” prompting him to flee to London, where he found his true calling. There is no surviving evidence for this story, but it has been a particularly enduring legend. It was first mentioned by Richard Davies (1635-1708) in the late seventeenth century and was later expanded upon by Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718) in 1709. Both biographers seem to have sourced the tale in rumors that were circulating around Stratford long after Shakespeare’s own death.

Interestingly, Baker’s catalog of plays lists several quarto editions of Shakespeare which are no longer extant. Although the First Folio is the only surviving textual source for the plays The Tempest, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Taming of the Shrew, King John, and Macbeth, Baker recorded quarto editions for each one, all pre-dating the First Folio. It is unclear if Baker was referring to quarto editions now lost to us or if Baker’s citations were simply erroneous and referred to publications that had never existed in the first place.