Edward Hall (1497-1547)

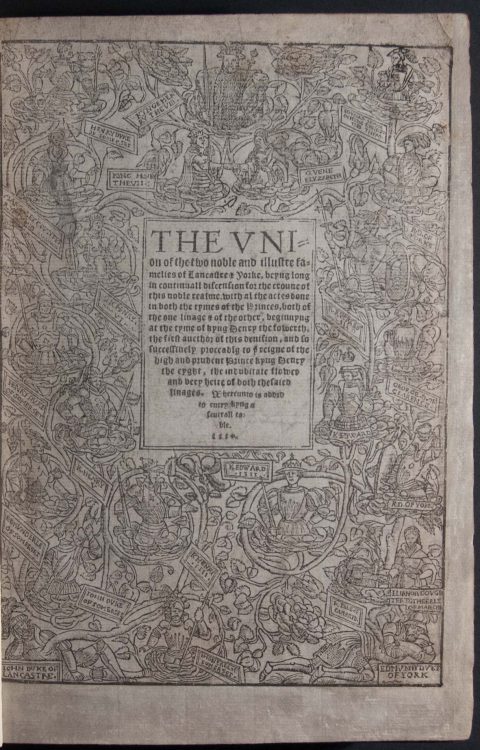

The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Famelies of Lancastre and Yorke, Beyng Long in Continnall Discension For the Croune of This Noble Realme. With Al the Actes Done in Both the Tymes of the Princes, Both of the One Image & of the Other, Beginnyng at the Tyme of Kyng Henry the Fowerth, the First Aucthor of this Deuision, and so Successiuely Proccading to ye Reigne of the High and Prudent Prince Kyng Henry the Eyght, the Indubitate Flower and Very Heire of Both the Saied Linages. Whereunto is Added to Every Kyng a Seuerall Table. London: Imprinted by Richard Grafton, 1550.

Edward Hall, a lawyer and at times a member of parliament, is today best remembered for his work as a historian. His chronicle of England, shown here in its second printing, began with the reign of Henry IV (1367-1413) and concluded with the death of Henry VIII (1491-1547) and the accession of Edward VI (1537-1553). Hall’s chronicle is among the sources that Shakespeare is known to have consulted when composing his history plays.

In a preface addressed to Edward VI, Hall suggested that writing could preserve knowledge and a legacy for all time, and that, in turn, would allow future generations to benefit from the examples - both good and bad - of their ancestors. The chronicle was thus advertised as a practical tool, one which would be of use to heads of state, such as the newly crowned king. The title page of the book, shown here, shows an illustrated lineage of the House of Tudor.

Hall’s chronicle appeared posthumously, in 1548. In an introduction, Richard Grafton (1506/7-1573), the printer, said that he had opted not to edit or alter any of Hall’s text, “for asmuche as a dead man is the aucthor thereof, I thought yt my ducty to suffer hys worke to be hys awne.” Grafton’s statement cannot be entirely true, though, as the chronicle covers some events that happened after Hall’s death. (Hall had actually bequeathed the chronicle to Grafton in his will, with the expectation that Grafton would see the book into print.) In 1555, the book was banned by Queen Mary (1516-1588) (Hall had expressed Protestant sympathies), although this did not prevent another edition from appearing in 1560. (Grafton would also go on to produce several histories of his own.)

Robert Fabyan (d. 1513)

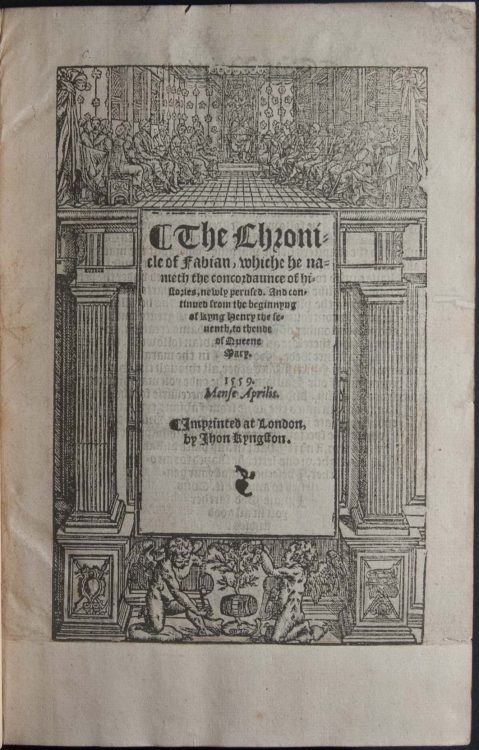

The Chronicle of Fabian: Whiche He Nameth the Concordaunce of Histories, Newly Perused. And Continued from the Beginnyng of Kyng Henry the Seuenth, to the Ende of Queene Mary. Imprinted at London: By Jhon Kyngston, 1559.

Robert Fabyan was a draper, sheriff, and alderman. He is best known for his history of England and France, The Newe Cronycles of England and France, often referred to as Fabian’s Chronicle. It was first published anonymously in 1516; Fabian’s own name did not appear in print until 1533. The Chronicle enjoyed great popularity in England, going through numerous editions. Interestingly, the subsequent editions of the Chronicle did not simply reprint the text as Fabyan had composed it. Instead, Fabyan’s editors continued on from where he had left off, in order to keep his history as up-to-date as possible. For example, in this copy, the title page states that the book goes up to April of 1559, concluding with the end of Queen Mary I’s (1516-1588) reign. However, the book is actually even more up-to-date coverage than the title promises, as it actually concludes on May 8, 1559, in the early days of Elizabeth I’s (1533-1603) reign. (Presumably, the publisher decided to supply additional sections while the book was being printed.)

Fabyan’s Chronicle served as one of the major sources for Shakespeare’s history plays. additionally, Fabyan was cited by the chronicles of Hall (1479-1547) and Holinshed (ca. 1525-1580), both of which, in turn, served as major sources for Shakespeare.

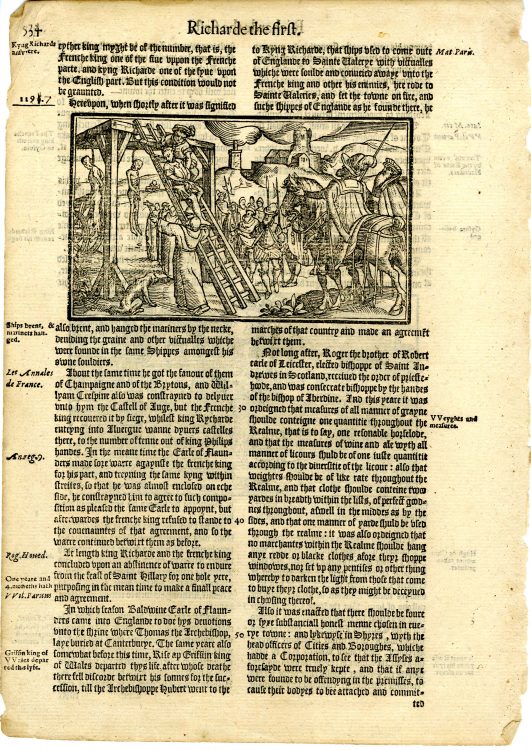

Single leaf from the first edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles

Single leaf from the first edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles: The Firste Volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande: Conteyning, the Description and Chronicles of England, from the First Inhabiting Vnto the Conquest. the Description and Chronicles of Scotland, from the First Originall of the Scottes Nation, Till the Yeare of Our Lorde. 1571. the Description and Chronicles of Yrelande, Likewise from the Firste Originall of That Nation, Vntill the Yeare. 1547. Faithfully Gathered and Set Forth, by Raphaell Holinshed. At London: Imprinted [by Henry Bynneman] for Iohn Harrison, 1577.

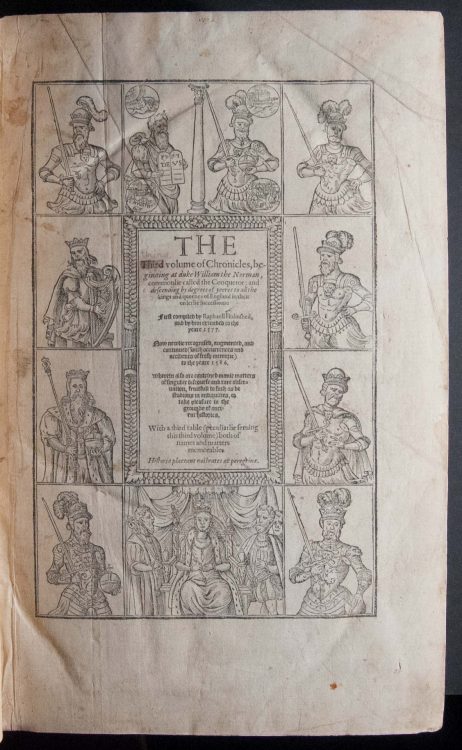

The Third Volume of Chronicles, Beginning at Duke William the Norman, Commonlie Called the Conqueror; and Descending by Degrees of Yeeres to all the Kings and Queenes of England in their Orderlie Successions. London: Printed in Aldergate Street at the Signe of the Starre, 1587.

The second printing of Holinshed’s Chronicles, shown here, was an important source for Shakespeare’s plays. Holinshed provided source material for all of Shakespeare’s history plays, as well as for the tragedies of Macbeth, King Lear, and Cymbeline.

Holinshed’s Chronicles began as a planned “universall cosmographie,” as envisioned by the printer Reginald Wolfe (d. 1573). Wolfe began working on this world history sometime around 1548, and recruited Raphael Holinshed as an assistant. Wolfe’s history remained unfinished at the time of his death and, as per his will, Holinshed continued on in his stead. At some point, though, the universal history was scaled back to a history and geography of the British Isles, from their mythical origins onwards. Additional contributions to the project came from Richard Stanihurst (1547-1618) and William Harrison (1547-1618) and, in 1577, a two-volume first edition of the Chronicles finally appeared in print. However, despite the nearly three decades that had gone into writing the Chronicles, the printing of the first edition appears to have been rushed, as Holinshed, Harrison, and Stanihurst all noted in their own introductions to the work.

The second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, as overseen by Abraham Fleming (ca. 1552-1607), presented an extensive rewriting and expansion of Holinshed’s original text, with the introduction of a great deal of new material, extensive quotations from original source texts, and a continuation of the history up to the present day. The new material was provided by Fleming and other collaborators, including William Harrison, John Stow (1524/5-1605), John Hooker (ca. 1527-1601), and Francis Thynne (1545?-1608), along with a new translation of Giraldus Cambrensis’ (ca. 1146-1223) Irish history.

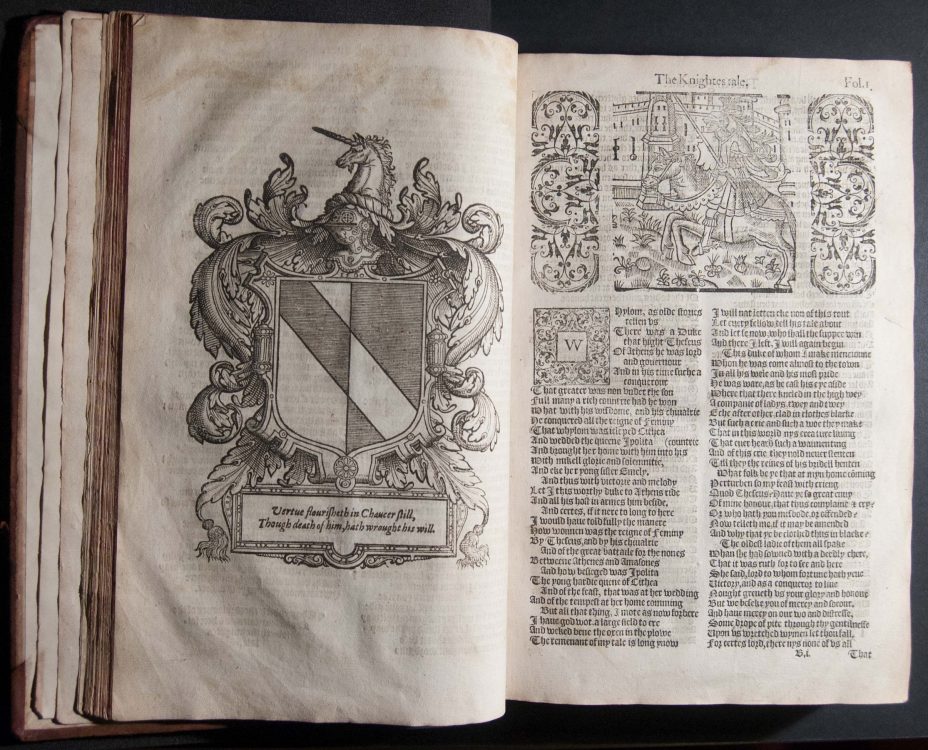

[The Workes of Our Antient and Learned English Poet Geffrey Chaucer, Newly Printed. London: Printed by Adam Islip, at the charges of Bonham Norton, 1598.]

The poet and administrator Geoffrey Chaucer, best known for his Canterbury Tales, was among the authors published by the first English printer, William Caxton (ca. 1422-1491), in the fifteenth century, and has been printed widely ever since. Prior to the invention of the printing press, Chaucer’s works were circulated extensively in manuscript, with at least 83 manuscripts of the Canterbury Tales still extant.

Chaucer’s “Knight’s Tale,” shown here, served as a source for Shakespeare’s collaborative play, The Two Noble Kinsmen. Additionally, Shakespeare also borrowed from Chaucer for Troilus and Cressida, and may have drawn inspiration from him for A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The edition of Chaucer on display was edited by Thomas Speght (d. 1621), a schoolmaster and antiquary. Speght had been a contemporary of Francis Beaumont the elder (d. 1598; father of the dramatist of the same name, Francis Beaumont) while they were students at Cambridge, and it was Beaumont who first inspired Speght’s interest in Chaucer. Speght’s Chaucer opens with a letter from Beaumont, seeking to refute the common complaints that Chaucer uses many difficult, obscure words, and that he is unnecessarily bawdy and offensive. Speght also provided a biography of Chaucer, which was not only the first written in English, but also the first to be based (in part) on research with official records. This biography also served as the basis for all subsequent accounts of Chaucer’s life up until the 1840s. Far from wholly accurate, however, Speght’s biography included a great number of spurious details. This edition also included an extensive glossary of “the old and obscure words of Chaucer, explaned” (also referred to, in the book, as “the hard words of Chaucer, explaned”), the first such compendium to appear in print, and a testament to the fact that the English language had changed a great deal in the nearly two centuries that separated Speght and Chaucer.

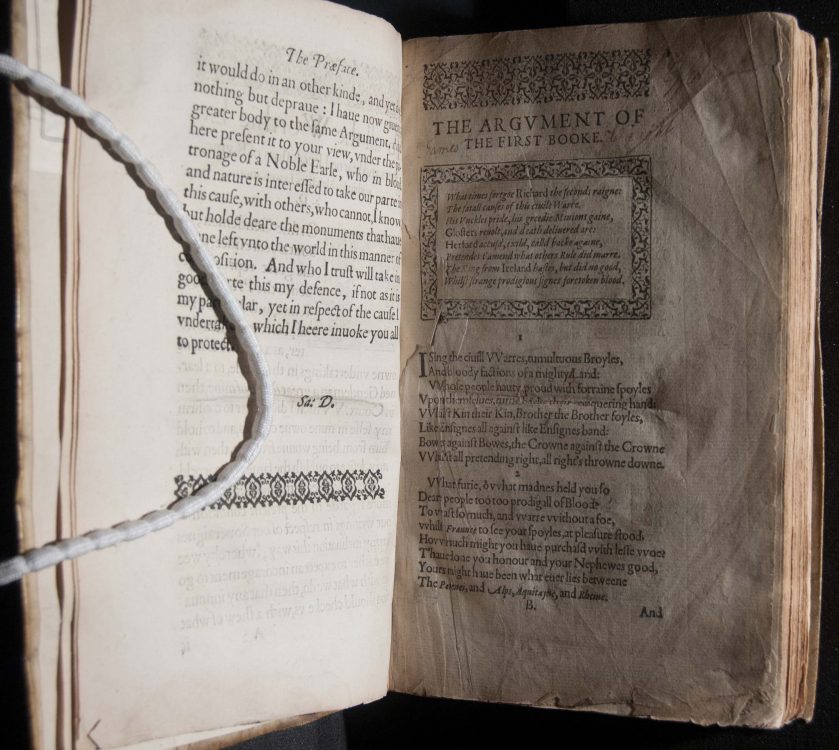

Samuel Daniel (1562-1619)

The Works of Samuel Daniel. [London: Printed for Simon Waterson,] 1602.

Samuel Daniel was an English poet and historian. His epic poem Civil Wars recounts the history of the wars between the Houses of Lancaster and York, beginning with the deposition of Richard II (1367-1400) and concluding with the death of Richard III (1452-1485), which paved the way for the Tudor dynasty. Published between 1595 and 1596 in two installments, the poem enjoyed great success. Shakespeare is known to have used the Civil Wars as a source for his history plays and, in the case of Richard II (believed to have been composed in 1595), Shakespeare was apparently reading and drawing from Daniel’s text just shortly after the poem’s publication.

The Civil Wars is shown here in the second edition of Daniel’s collected works. The first edition of his Works had been printed in 1601, with the second edition appearing just a year later.