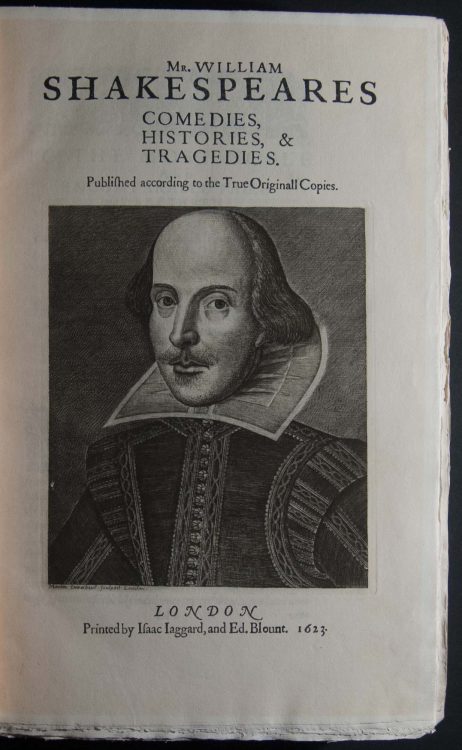

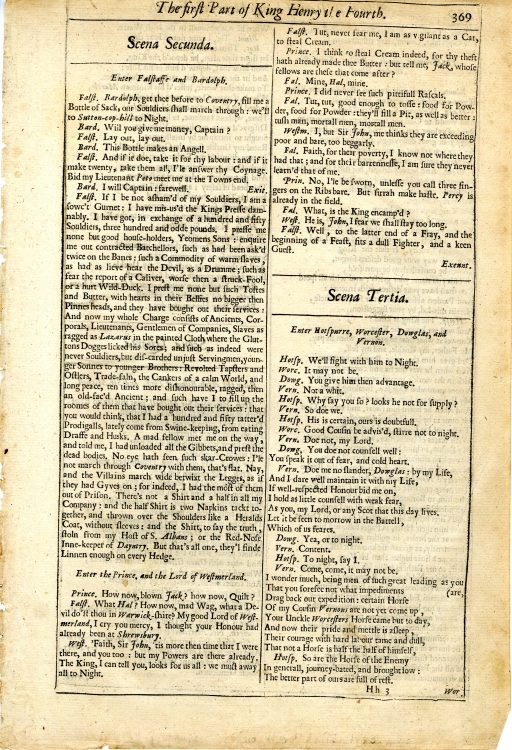

Facsimile of the First Folio

Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. Published According to the True Originall Comedies. London: Printed by Isaac Iaggard and Ed, Blount, 1623. (Facsimile: London: Methuen, 1910.)

At the time of his death in 1616, Shakespeare’s published legacy was limited to twenty plays that had been printed in cheap, often inaccurate editions. Shakespeare’s own colleagues would later refer to these editions as fraudulent and inaccurate, “maimed, and deformed by the frauds and stealhes of inurious impostors.” Shakespeare himself seems to have been indifferent to publication, and this attitude would have been in keeping with the ephemeral status that plays held in his day.

In 1623, however, the collected plays of Shakespeare appeared in a large (and expensive) folio-sized volume published by Isaac Jaggard (d. 1627) and Edward Blount (active 1588-1632), Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, which would later be known as the First Folio. The text was assembled by Henry Condell (d. 1627) and John Heminges (ca. 1556-1630), the two surviving members of Shakespeare’s company, the King’s Men. Condell and Heminges had acted alongside Shakespeare (they were also two of only three colleagues whom Shakespeare listed in his will), and they would presumably have had access to the play scripts that had been used by the King’s Men. In addition to providing accurate versions of plays that had previously appeared in quarto, the First Folio printed 18 plays which had never before been published, and would likely have otherwise been forever lost, among them being Macbeth, Julius Caesar, Twelfth Night, and The Tempest. The editors of the First Folio also introduced the division of Shakespeare’s plays into comedies, histories, and tragedies. The book opened with a series of elegies in memory of Shakespeare, written by men who would have known Shakespeare in life, including two by his friend and rival, Ben Jonson (ca. 1573-1637). The First Folio also presented a portrait of Shakespeare, as engraved by Martin Droeshout (b. 1601). Scholars have long questioned the accuracy of this posthumous portrait. Still, the engraving must have at least seemed suitable for a book assembled by people who had known Shakespeare well in life.

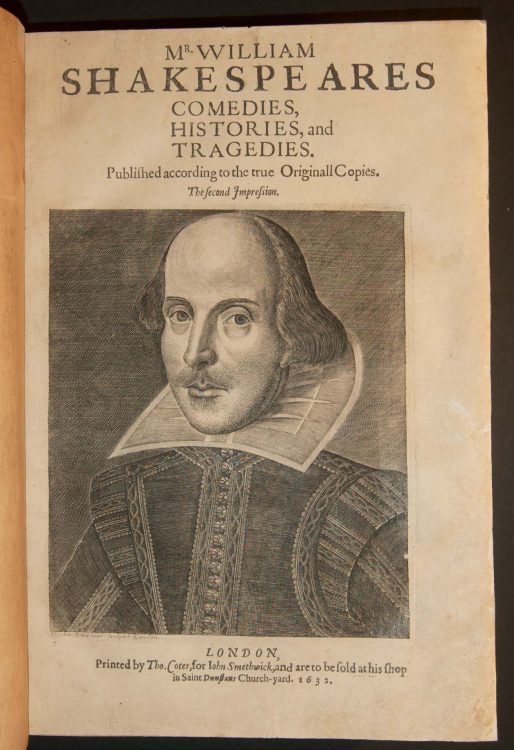

The Second Folio

Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies Published According to the True Originall Copies. London: Printed by Tho. Cotes, for John Smethwick, and are to be sold at his shop in Saint Dunstans Church-yard, 1632.

Nine years after the printing of the First Folio, Shakespeare’s works were printed for a second time, in a volume now known as the Second Folio. This edition was published collaboratively between five different publishers, presumably in order to reduce their financial risk. The printer of the Second Folio, Thomas Cotes (d. 1641), had been an apprentice to William Jaggard (ca. 1568-1623), publisher of the First Folio. Following the deaths of Jaggard and his son, Isaac (d. 1627), Cotes and his brother, Richard (d. 1653), acquired Jaggard’s printing rights from Isaac Jaggard’s widow, Dorothy. Robert Allot (active 1625-1636?), the principal publisher behind the Second Folio, had received his printing rights from Edward Blount (active 1588-1632), one of the other publishers behind the First Folio. Of the remaining publishers, two of them, John Smethwick (d. 1641) and William Aspley (d. 1640), had also collaborated with Jaggard and Blount on the First Folio.

The Second Folio was not a mere reprint of the text of the First Folio. The editors of the Second Folio made a conscious and systematic effort to correct the various errors that had crept into the First Folio. In particular, the editors were able to correct passages in which the First Folio’s editors had rendered lines in French, Latin, and Greek inaccurately (and, in some cases, insensibly). Still, the editors and typesetters inevitably introduced new errors of their own, any number of which were retained by successive editions. Today, the text of the Second Folio remains an important source in determining accurate texts of Shakespeare’s works.

Also new to the Second Folio was an anonymous elegy to Shakespeare, “An Epitaph on the admirable Dramticke Poet,” which had been written by a young John Milton (1608-1674), whose father was one of Cotes’ neighbors. The poem, which praises the Folio as a monument and a tomb that kings “would wish to die” for, was the poet’s first ever published writing.

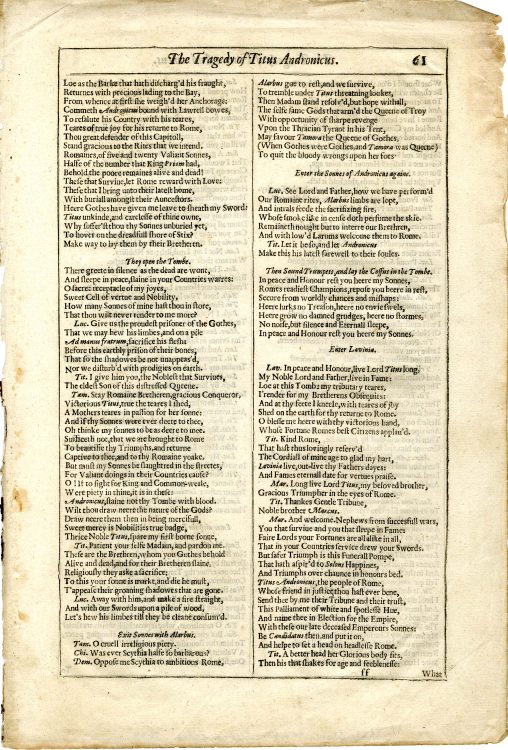

Single leaf from the Second Folio

Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies Published According to the True Originall Copies. London: Printed by Tho. Cotes, for John Smethwick, and are to be sold at his shop in Saint Dunstans Church-yard, 1632.

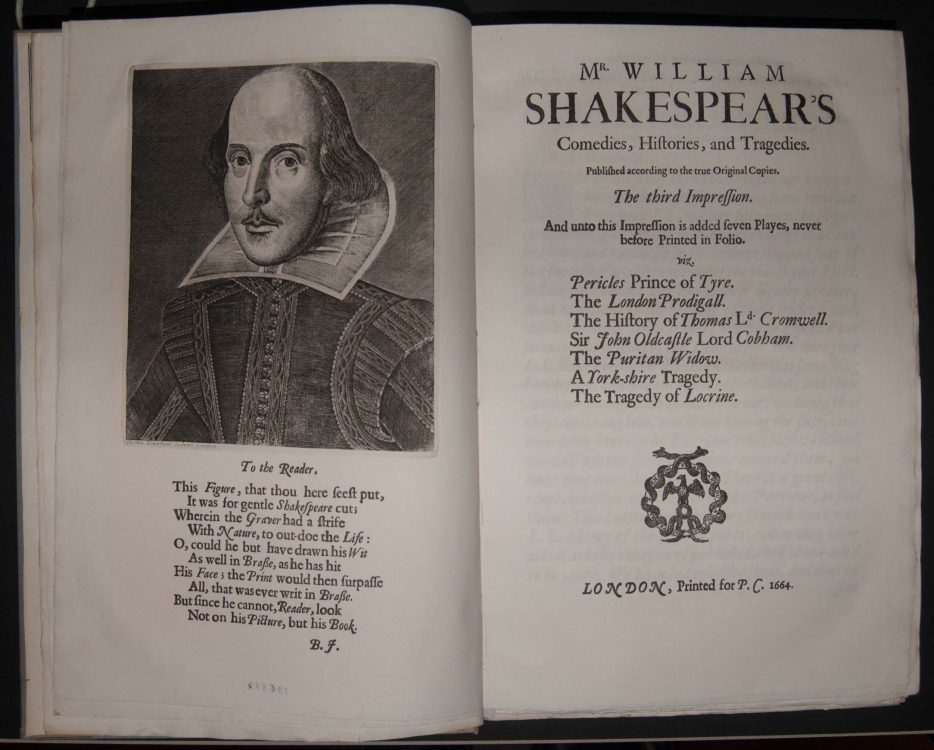

Facsimile of the Third Folio

Mr. William Shakespear’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies. Published According to the True Original Copies. London: Printed for P. C., 1664. (Facsimile. London: Metheun & Co., 1905).

The third collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays, the Third Folio, was published by Philip Chetwind (active 1653-1680), a cloth-worker whose wife Mary was the widow of Robert Allot (active 1625-1636?), the principal publisher behind the Second Folio. The first imprint of the Third Folio appeared in 1663 and reprinted the same collection of plays that had appeared over thirty years ago in the Second Folio. A year later, though, Chetwind issued a new imprint of the Third Folio, containing seven new Shakespeare plays. On the title page of the book, Chetwind advertised them as plays “never before Printed in Folio,” which was technically true, although he was stretching the truth a bit, since all of these plays had previously appeared in quarto editions. Of these seven plays, only one of them, Pericles, is now regarded as canonical. Chetwind was by no means the first person to attribute them to Shakespeare. All of them had previously appeared in quarto editions that identified them as Shakespeare’s work, making it understandable that Chetwind would have thought that they were worth including.

A fourth and final folio edition of Shakespeare would appear twenty-one years later, in 1685. Each edition attempted to correct the errors of the previous Folio, but each one also introduced new textual errors of its own, nor is it likely that seventeenth editors would have turned to earlier folio and quarto editions for clarification. For many years, this Fourth Folio would serve as the definitive text of Shakespeare, with many editors little realizing (or caring) that Shakespeare’s text had grown increasingly corrupted in the sixty-two years since the First Folio’s publication.

Single leaf from the Third Folio

Mr. William Shakespear's Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies. Published According to the True Original Copies. the Third Impression. and Unto This Impression Is Added Seven Playes, Never Before Printed in Folio. Viz. Pericles Prince of Tyre, the London Prodigall, the History of Thomas Ld. Cromwell, Sir John Oldcastle Lord Cobham, the Puritan Widow, a York-Shire Tragedy, the Tragedy of Locrine. London: Printed for P.C, 1664.

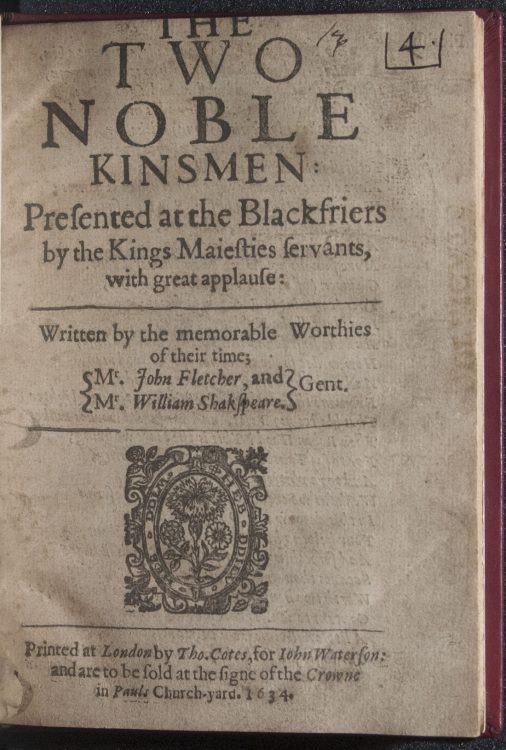

William Shakespeare and John Fletcher (1579-1625)

The Two Noble Kinsmen: Presented at the Blackfriers by the Kings Maiesties Servants, with Great Applause: Written by the Memorable Worthies of Their Time; Mr. Iohn Fletcher, and Mr. William Shakspeare. Gent. Printed at London: by Tho. Cotes, for Iohn Waterson: and are to be sold at the signe of the Crowne in Pauls Church-yard, 1634.

Printed plays accounted for only a very small (and fairly unprofitable) portion of the English book trade. Playwrights had little incentive to publish their works, since they could best expect to make a profit performing plays, not publishing them. When plays were published, they typically appeared in a small, quarto-sized format, as shown here. These volumes were printed cheaply and were sold as ephemeral items; they were not expected to survive. These copies were also not necessarily authorized. Intellectual copyright did not exist at the time: the only copyright in existence was the printing rights given to a publisher who had secured permission from the Stationer’s Company to publish a particular text.

The quarto volume shown here contains the first printing of The Two Noble Kinsmen, which was written as a collaborative effort between Shakespeare and John Fletcher. (Scholars differ in their interpretations of the roles that the two playwrights had in this work. As there is no extant documentation of the play’s composition, any speculation about the nature of their collaboration can only come from internal evidence in the play itself.) The play appears to have been written between 1613-1614, with its first performance occurring around that same time. Subsequent performances occurred in 1619-1620 and 1625-1626. This quarto was printed to accompany a revival of the play (as is advertised on the title page). Scholars speculate that the quarto may have been based on a scribal transcription that had been further revised for the subsequent performances. If so, this would make the quarto a reasonably accurate version of the text. Following its appearance in quarto, The Two Noble Kinsmen would not appear in print again until 1679, when it was included in the second edition of Beaumont and Fletcher’s works, sans any mention of Shakespeare’s contribution.