William Shakespeare

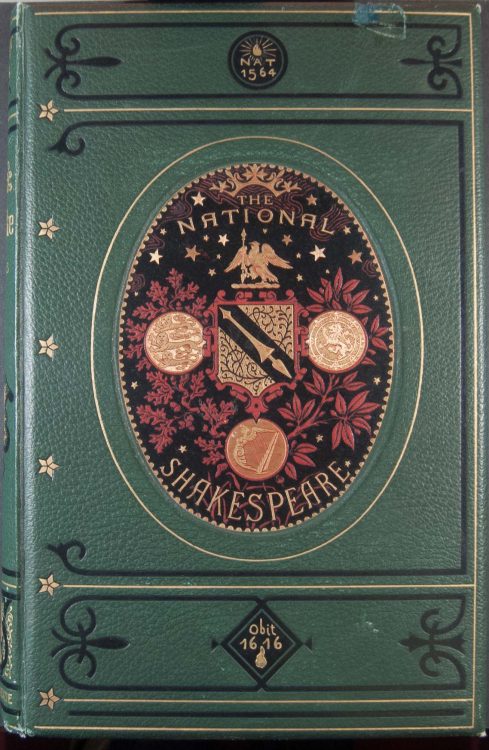

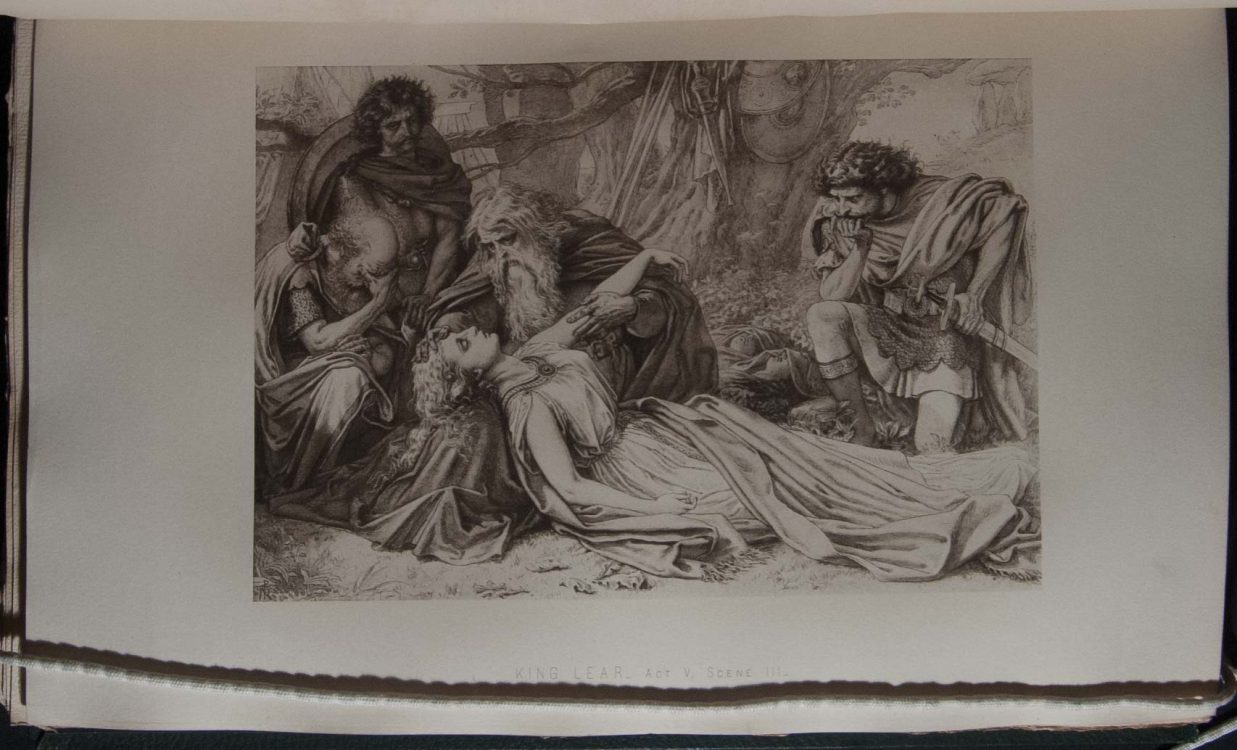

The National Shakespeare: A Fac-Simile of the Text of the First Folio of 1623. London: William Mackenzie, [1888-1889.]

William Shakespeare

The National Shakespeare: A Fac-Simile of the Text of the First Folio of 1623. London: William Mackenzie, [1888-1889.]

The National Shakespeare was advertised as a type facsimile of the First Folio, “printed in a special antique type, such as was actually employed in the ‘First Folio.’ ” This was not true, though. The National Shakespeare presented the text of the First Folio in a modernized type, with inconsistent attempts to approximate the typeface and decorative designs employed by William Jaggard in 1623. The layout of the text was also altered in places, in some cases so drastically so as to bear no real relation to the printed appearance of the 1623 edition. The National Shakespeare also featured twenty illustrations based on paintings by Joseph Noël Paton (1821-1901) and reproduced using the then-new technology of photographic engraving.

In their advertisement, the publisher of the National Shakespeare also noted a curious new reason for interest in the text of the First Folio: an American critic (there unnamed) had recently suggested that the First Folio’s “numerous and surprising typographical errors, which have long been considered its chief blemishes, are in fact essential portions of an elaborate cypher” which, when decoded, would supply a “second or hidden narrative” attesting to the plays having been written not by William Shakespeare, but by Francis Bacon (1561-1626). The publisher expressed skepticism (“we may well hesitate to accept it without a much more exhaustive scrutiny than it has yet received”), but he also seemed unwilling to outright dismiss a claim that - however absurd - would provide one more selling point for a book containing the exact text of the First Folio.

William Shakespeare

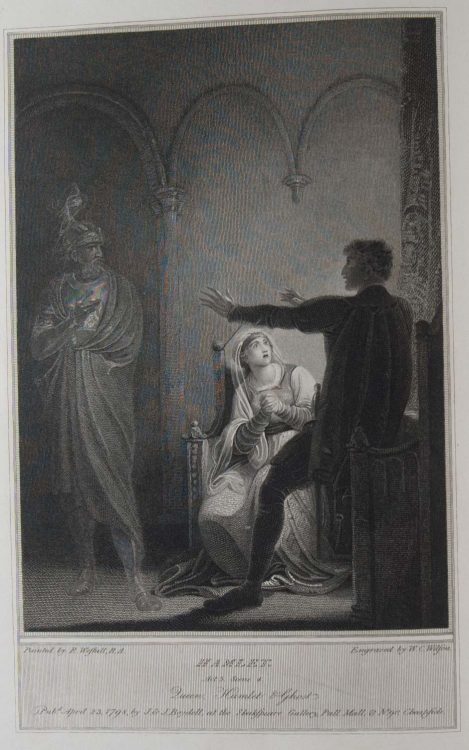

The Dramatic Works of Shakspeare. London: Printed by W. Bulmer and Co., Shakspeare Printing Office, for John and Josiah Boydell, George and W. Nicol, from the types of W. Martin, [1791]-1802 [i.e., 1803].

John Boydell was an alderman and a print-seller. In the late eighteenth century, he began planning to produce a luxury edition of Shakespeare that would pair a scholarly text with artistic engraved illustrations. At the time, Boydell was in the midst of a long and successful career in the print trade, and he was even credited with having improved the quality of English engraving by commissioning high-end engravings to compete with those being made in continental Europe. He advertised his Shakespeare as a great national contribution to English art and, to this end, he commissioned a series of paintings by leading artists, which would then be engraved for reproduction in the printed set. Boydell’s Shakespeare represented a massive investment and a great financial risk. In order to print the set to his standards, he established his own printing house, type foundry, and ink manufacturer. Boydell also created an art gallery, in which the Shakespeare paintings were displayed to the public (and thus, advertised to potential buyers of the printed set).

Boydell’s Shakespeare was issued in 18 parts between 1791 and 1803, with a text edited by George Steevens (1736-1800). (Steevens, who finished preparing the text in 1793, did not live to see the Boydell Shakespeare into print.) Although Boydell’s Shakespeare gallery was very successful, the printed book did not fare as well. The Boydell Shakespeare suffered from poor timing: it took so long to print that the finished set hit the market in the midst of the Napoleonic Wars, which effectively eliminated any market for luxury volumes in continental Europe. Some critics also complained that the quality of the engravings did not quite live up to what Boydell had promised. James Northcote, one of Boydell’s own contributors, complained that the set presented “such a collection of slip-slop imbecility as was dreadful to look at.” The project left Boydell financially ruined. In order to pull himself out of bankruptcy, he held a lottery, with the grand prize being the original paintings as well as the lease to the gallery in which they resided. The lottery was a resounding financial success, although Boydell died before he could benefit from it, with the proceeds instead passing on to his nephew and business partner, Josiah Boydell (1752-1817).

Henry Noel Humphreys (1810-1879)

Sentiments and Similes of William Shakespeare. A Classified Selection of Similes, Definitions, Descriptions, and Other Remarkable Passages in the Plays and Poems of Shakespeare. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1851.

In the preface to Sentiments and Similes, Henry Noel Humphreys says that he opted to make an illuminated book of Shakespeare quotations because no other author or subject seemed more worthy and suited to “the latest refinements in decorative printing” than “our immortal Shakespeare.” He wrote that he hoped to place Shakespeare’s words “worthily in a fitting casket - to enshrine them, as it were, in a reliquary as rich as a combination of the typographic and lithochromic arts could form.” The resulting book places selections from Shakespeare - arranged according to topics such as ambition, beauty, honor, and fame - adorned with printed illuminations. The book also features a decorative papier-mâché binding with an inset bust of Shakespeare.

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare's Household Words, A Selection from the Wise Saws of the Immortal Bard. London: Griffith & Farran, [circa 1859.]

This collection of Shakespeare’s sayings was decorated with printed illuminations by Samuel Stanesby. As in many of the books on display in this case, color lithography was used to create printed designs which imitated the decorative illuminations that had once been employed in medieval manuscripts.

William Shakespeare

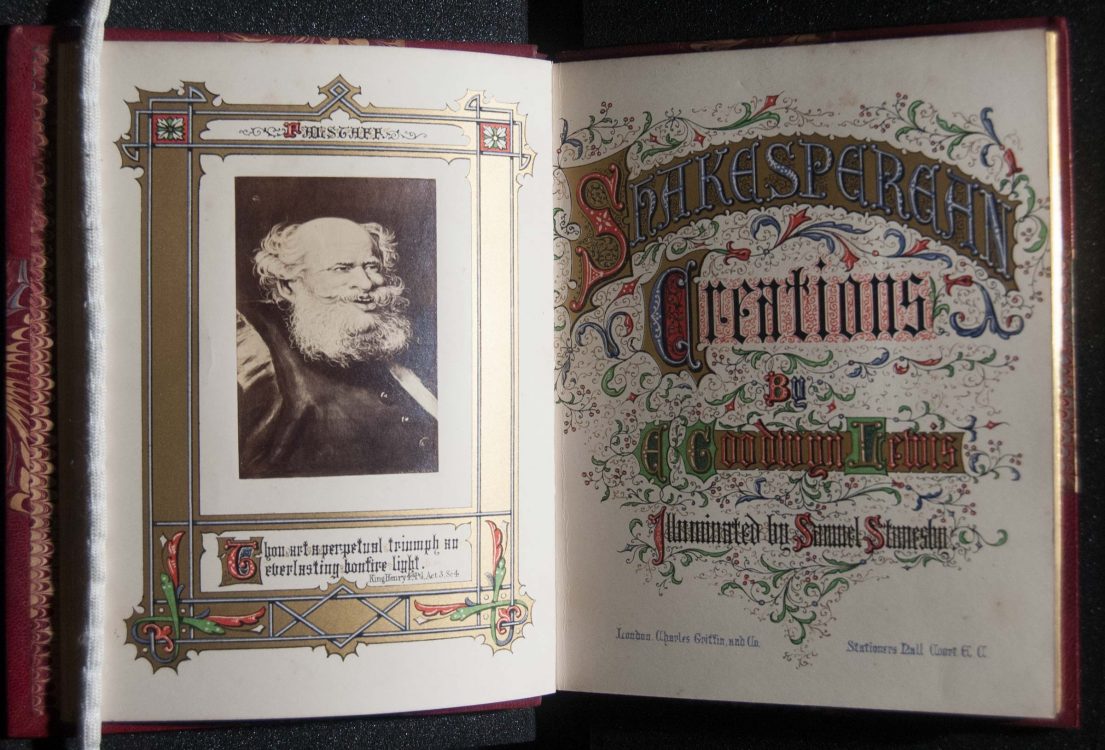

Shakespearean Creations. London: Charles Griffin & Co., [circa 1860s].

Shakespearean Creations featured photographic reproductions of paintings by E. Goodwyn Lewis (1827-1891), which were paired with illuminations by Samuel Stanesby and selected quotations from Shakespeare’s plays. This copy contains a note that it was Stanesby’s personal copy.