N. E. S. A. Hamilton (d. 1915)

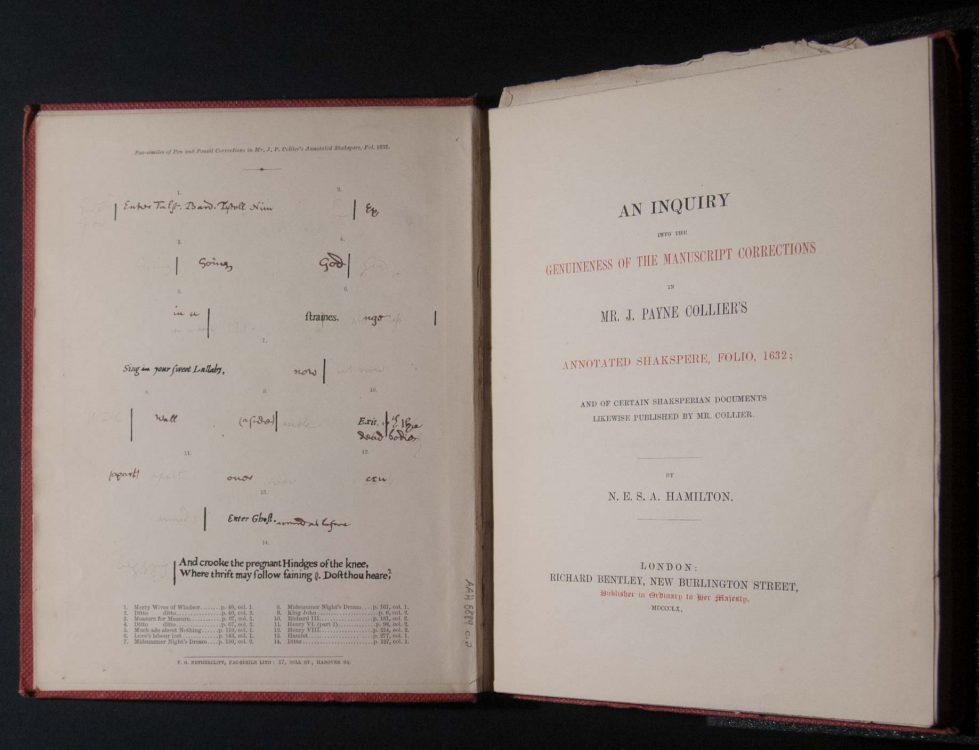

An Inquiry into the Genuineness of the Manuscript Corrections in Mr. J. Payne Collier's Annotated Shakspere, Folio, 1632; And of Certain Shaksperian Documents Likewise Published by Mr. Collier. London: Richard Bentley, 1860.

In 1852, John Payne Collier (1789-1883), a respected Shakespeare scholar and editor, announced that he had discovered a Second Folio of Shakespeare - referred to as the Perkins Folio, for an ownership inscription in the book - that was heavily annotated and corrected in a mid-seventeenth-century hand. Many of the emendations provided plausible corrections to Shakespeare’s text, ranging from minor changes in punctuation to revised stage directions and entirely new lines. Between 1842 and 1844, Collier published transcripts of the annotations as part of a new edition of Shakespeare’s work, positing his theory that they represented genuine corrections to Shakespeare’s plays. He went one step further in 1844 by publishing an edition of Shakespeare that incorporated these alternate readings as part of the text proper.

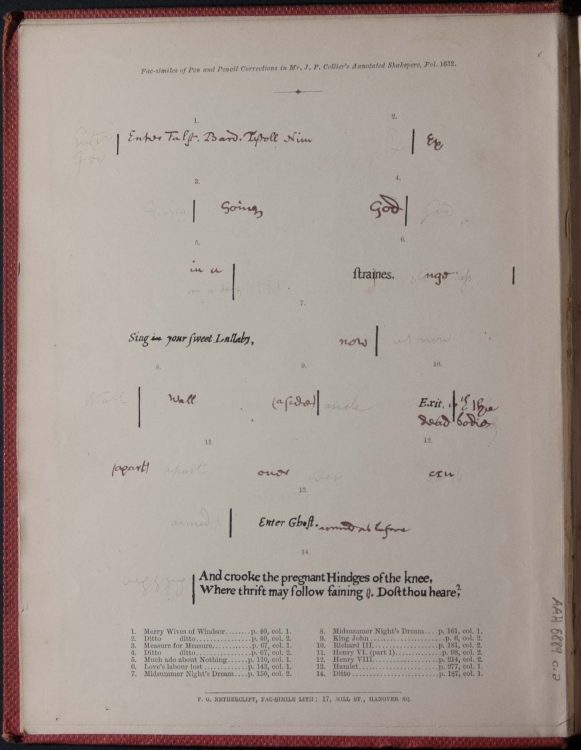

Understandably, the Perkins Folio generated a great deal of interest, as well as a great deal of controversy. Somewhat suspiciously, Collier refused to let anyone look at the Perkins Folio, which he had deposited in the library of his patron, the Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858). After the Duke’s death, the Perkins Folio was bequeathed to the British Museum, at which point Collier’s claims began to unravel. Several experts at the British Museum - Frederic Madden (1801-1873), keeper of manuscripts; N.E.S.A. Hamilton (d. 1915), Madden’s assistant; and Nevil Maskelyne (1823-1911), keeper of minerals - performed a thorough analysis of the Perkins Folio and concluded that the annotations were actually nineteenth-century forgeries written in imitation of seventeenth-century script. (Additionally, with the use of a microscope, they were able to confirm that some of the annotations had been written in ink over penciled annotations that had been composed in a modern hand.)

Curiously, this was by no means the first time that Collier had produced scholarship that relied on fraudulent sources. Previously, his History of English Dramatic Poetry and Annals of the Stage (1831) had cited a number of sources that either did not exist or were based on forged documents, even though the book was otherwise a fairly serious and thorough piece of scholarship.

N. E. S. A. Hamilton (d. 1915)

An Inquiry into the Genuineness of the Manuscript Corrections in Mr. J. Payne Collier's Annotated Shakspere, Folio, 1632; And of Certain Shaksperian Documents Likewise Published by Mr. Collier. London: Richard Bentley, 1860.

Hamilton and Maskelyne first published three letters in The Times in July 1859, in which they summarized their findings and concluded that the annotations in the Perkins Folio were fraudulent. Collier replied that same month by insisting that the annotations were genuine and that they had been present in the book when he purchased it. Although Hamilton and Maskelyne had not gone so far as to accuse him of doing so, Collier also insisted that he was not responsible for forging the annotations. The following year, Hamilton responded with this book, in which he summarized the British Museum’s full analysis and affirmed that the annotations had been forged.

The plate facing the title page shows reproductions of the forged “seventeenth-century” annotations, alongside the twentieth-century penciled annotations, which were believed to have been composed by the forger as guides prior to attempting the forgeries.

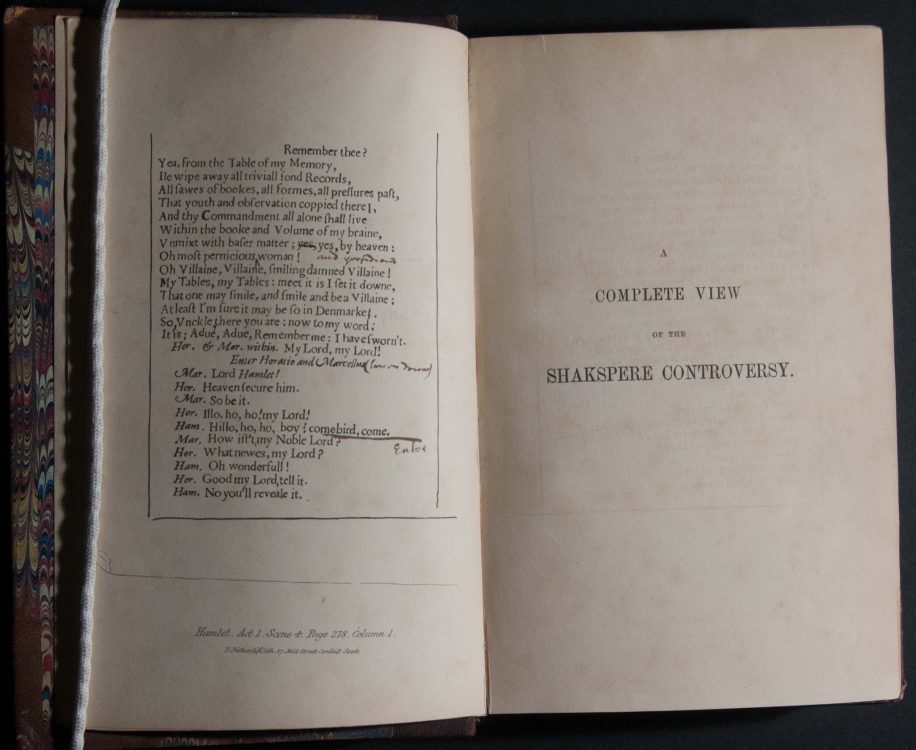

C. M. Ingleby (1823-1886)

A Complete View of the Shakspere Controversy: Concerning the Authenticity and Genuineness of Manuscript Matter Affecting the Works and Biography of Shakspere. London: Nattali and Bond, 1861.

In 1859, C. M. Ingleby published The Shakespeare Fabrications, in which he argued that the annotations in the Perkins Folio were fraudulent. Although he did not go quite so far as to outright accuse Collier of personally producing the forgery, he did the next best thing by observing that the penciled annotations appeared to be “in the handwriting of someone who wrote exactly like Mr. Collier.” His Complete View of the Shakespere Controversy, published two years later, was the last word on the subject. He summarized all of the existing evidence against the Perkins Folio and accused Collier of producing the annotations himself, thereby inflicting a “foul libel on the pure genius of Shakspere.” Collier refused to respond further, and, eventually, interest in the matter faded. Curiously, the scandal did not follow him: Collier continued to go about his work as a scholar, and even produced one more edition of Shakespeare between 1875 and 1878.