Before the Civil War, suffrage—the right to vote—was one among many demands of a vibrant American women’s rights movement. It was a demand made at the 1848 Seneca Falls and Rochester Women’s Rights Conventions and in 1840s petitions to state constitutional conventions. But the original U.S. Constitution (1787) was silent on the question of voting rights. The states, not the federal government, established qualifications for voting.

The Fourteenth (1868) and Fifteenth (1870) Amendments to the Constitution changed that by defining national citizenship, outlining citizens’ fundamental rights (Fourteenth) and stating that citizens could not be denied the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude” (Fifteenth).

Voting’s importance to the broader rights of citizens increased immeasurably as a result. Once all men—in theory at least—possessed the right to vote, then women’s lack of access to voting became the most visible and obvious way in which women were disadvantaged as citizens. An independent women’s suffrage movement came into being during the 1860s, focusing on voting as a key women’s right.

As suffrage became increasingly important to discussions of women’s citizenship rights, supporters took to print and to the courts to state their positions. Some, such as Delaware-born Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) voted or attempted to vote. Historians have documented hundreds of such efforts by both African American and white suffragists between 1869 and 1874. Most famously, Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906) and fourteen others were arrested in 1872 in Rochester, New York, for illegal voting. In 1875, in the case of Minor v. Happersett, the Supreme Court affirmed that states were the primary arbiters of who had the right to vote.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS – WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE - The titles of John Todd’s and Gail Hamilton’s works provide a shorthand introduction to post-Civil War debates about the rights women should have. Todd, a Congregationalist minister, took the position that the demand for “woman’s rights” was unnatural and ungodly. “God never designed that woman should occupy the same sphere as man.”

The American writer and essayist Mary Abigail Dodge was an early champion of pay equity for women authors. Writing under the pseudonym of Gail Hamilton, she composed a direct response to Todd, wielding her knowledge and experience to denounce his views as being opposed to Scripture. “Christ made no distinction, but opened the door wide to woman as to man.” At the same time, she challenged those who envisioned suffrage as the solution to “woman’s wrongs.” “Give (women) the ballot, that they may see for themselves how little it can do.”

- John Todd (1800-1873). Woman’s Rights (Tracts for the People). Boston : Lee and Shepard, 1867.

- Gail Hamilton (pseudonym for Mary Abigail Dodge, 1833-1896). Woman’s Wrongs: A Counter-Irritant. Boston : Ticknor and Fields, 1868. Author’s presentation copy, dated January 18, 1869.

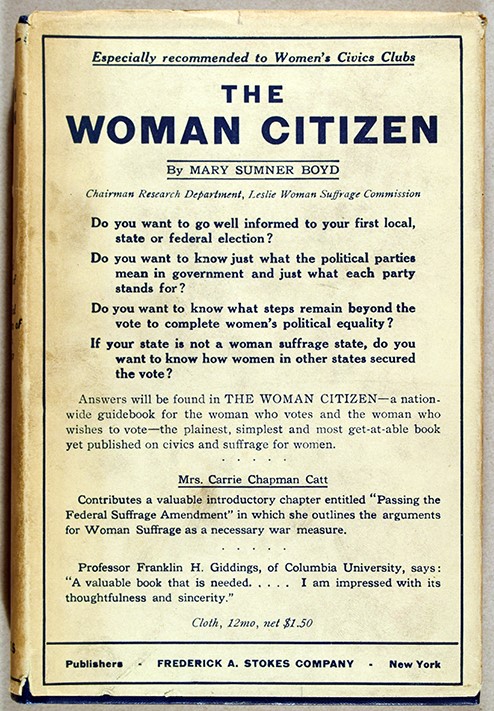

In 1918, expressing confidence that Congress would soon pass the 19th Amendment and send it to the states for ratification, NAWSA President Carrie Chapman Catt endorsed The Woman Citizen as a guide for women who already enjoyed voting rights in their states. The book included a chart listing individual states’ suffrage qualifications. The notation “W.S.” offered evidence for the patchwork nature of state-by-state suffrage.

- Mary (Mary Brown) Sumner Boyd (1876-1950). The Woman Citizen: A General Handbook of Civics, with Special Consideration of Women’s Citizenship. New York : Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1918.

![John Todd (1800-1873). Woman’s Rights [Tracts for the People]. Boston : Lee and Shepard, 1867 John Todd (1800-1873). Woman’s Rights [Tracts for the People]. Boston : Lee and Shepard, 1867](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/votes-for-delaware-women/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2020/04/DSC_0283-Todd-Womans-Rights.jpg)

![Gail Hamilton [pseudonym for Mary Abigail Dodge] (1833-1896). Woman’s Wrongs: A Counter-Irritant. Boston : Ticknor and Fields, 1868 Gail Hamilton [pseudonym for Mary Abigail Dodge] (1833-1896). Woman’s Wrongs: A Counter-Irritant. Boston : Ticknor and Fields, 1868](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/votes-for-delaware-women/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2020/04/DSC_0282-Hamilton-Womans-Wrongs.jpg)