Long-standing ties between American and European women’s rights advocates led to the creation of the International Council of Women in 1888, and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904. NAWSA leader Carrie Chapman Catt served as the Alliance’s president from 1903 until 1923, regularly reporting to the membership on the progress of suffrage efforts in other countries.

Britain’s militant “suffragettes,” personified by the mother-daughter team of Emmeline and Sylvia Pankhurst, stalwarts in the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), favored a direct, confrontational style of campaigning of the sort seen in international labor and anti-colonial movements. Members not only marched and picketed, they engaged in civil disobedience, including window-smashing, arson, and even fire-bombing. For her role, Emmeline Pankhurst went to prison, began a hunger strike, and endured the torture of forcible feeding.

The WSPU had a direct influence on the American suffrage movement through the experiences of suffragists such as Harriot Stanton Blatch, Alice Paul, and Lucy Burns, who participated in WSPU demonstrations while living in England. Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), was arrested at a WSPU demonstration and undertook her first hunger strike as a result. As a pacifist, however, she rejected violence.

In 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst visited Wilmington on a lecture tour. Hosted by Mabel Vernon and the local branch of the Congressional Union (CU), she stopped off to give a lecture and have tea at the Hotel du Pont. Although British activists used the term “suffragette” for themselves, Americans generally considered the diminutive word demeaning and insisted on being called “suffragists.”

Selections here reflect trans-national connections among suffrage groups. Kentucky-born actor and playwright Elizabeth Robins moved to London in 1888, where her 1907 play “Votes for Women!” inaugurated a vogue for suffrage-themed theatre pieces. She joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) until alienated by the group’s tactics. Her 1913 book, Way Stations, collected her suffrage speeches and essays, which would, as the publisher advertised, be “invaluable to suffrage workers.”

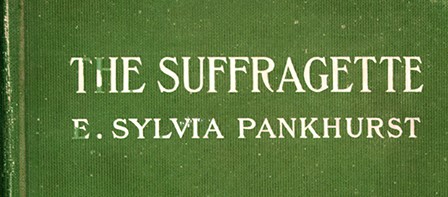

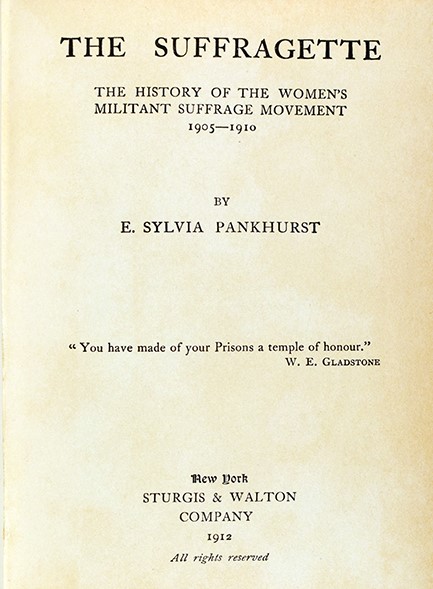

Although the European war made ocean-going travel almost impossible after the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915, Americans read and circulated works by British suffragettes, including Emmeline and Sylvia Pankhurst. The Pankhursts’ Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was known for its use of militant—indeed violent—tactics to call attention to demands for voting rights. Emmeline Pankhurst’s autobiography, published just as the Great War began, included her organization’s decision to call a suffrage “truce” for the war’s duration. American militant suffragist Alice Paul, founder of the National Woman’s Party, who first encountered militant methods while living and studying in England, did not follow suit.

- Elizabeth Robins (1862-1952). Votes for Women! A Dramatic Tract in Three Acts (programme). London : Royal Court Theatre, 1907. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection

- E. Sylvia (Estelle Sylvia) Pankhurst (1882-1960). The Suffragette : The History of the Women’s Militant Suffrage Movement, 1905-1910. New York : Sturgis and Walton, 1912.

- Emmeline (Emmeline Goulden) Pankhurst (1858-1928). My Own Story. New York : Hearst International Publishing Company, 1914.

- Elizabeth Robins (1862-1952). Way Stations. New York : Dodd, Mead and Company, 1913.

- New York State Woman Suffrage Party. “Suffrage as a War Measure” (leaflet). New York : National Woman Suffrage Publication Co., October 1917. Woman Suffrage Collection.

![Elizabeth Robins (1862-1952). Votes for Women! A Dramatic Tract in Three Acts [programme]. London : Royal Court Theatre, 1907. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection Elizabeth Robins (1862-1952). Votes for Women! A Dramatic Tract in Three Acts [programme]. London : Royal Court Theatre, 1907. Mark Samuels Lasner Collection](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/votes-for-delaware-women/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2020/04/program-royal-court-theatre-open1.jpg)

![Suffrage as a War Measure [leaflet center pages]. New York : National Woman Suffrage Publication Co., October 1917. Woman Suffrage Collection Suffrage as a War Measure [leaflet center pages]. New York : National Woman Suffrage Publication Co., October 1917. Woman Suffrage Collection](https://exhibitions.lib.udel.edu/votes-for-delaware-women/wp-content/uploads/sites/96/2020/04/MSS0477_F007_001b.jpg)